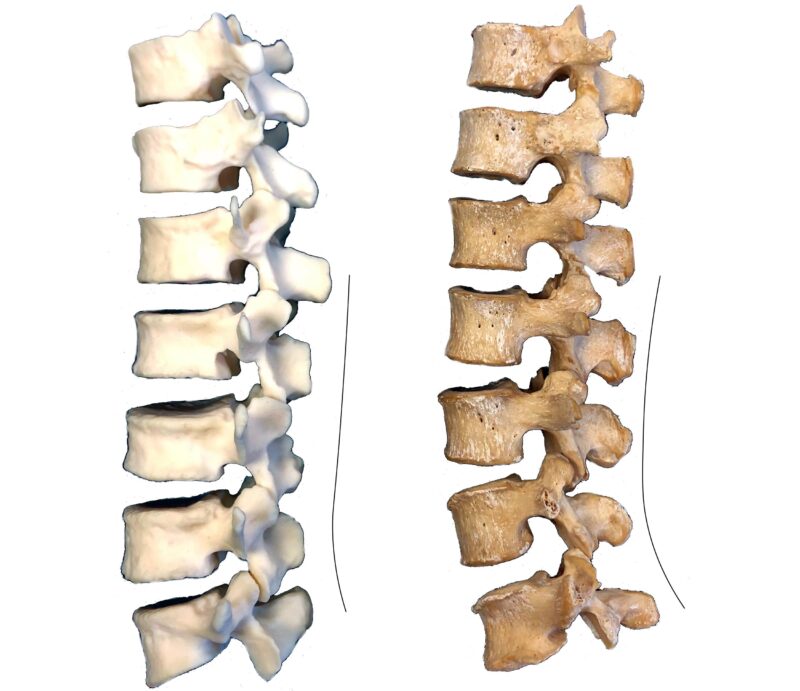

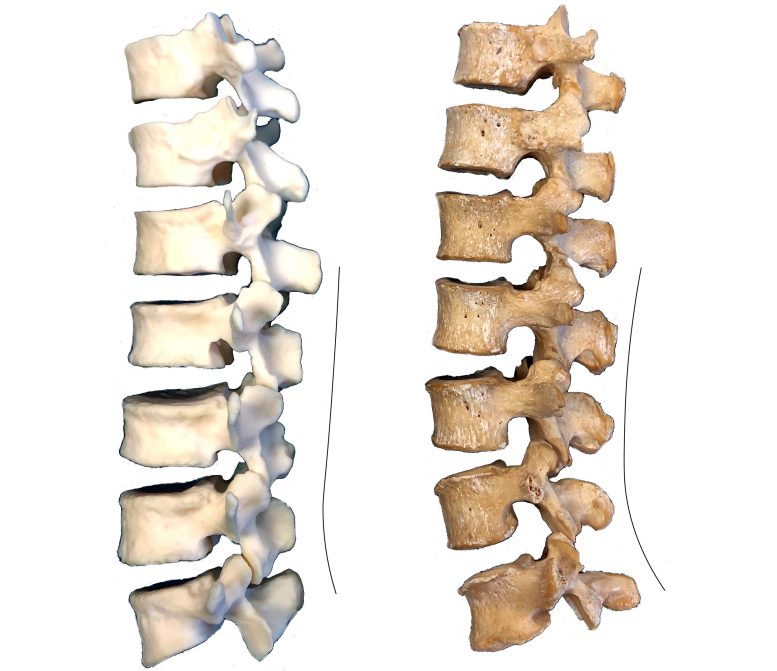

Os du bas du dos d’un Néandertalien (spécimen Kebara 2 ; à gauche) et d’un humain moderne postindustriel (à droite) montrant des différences dans le calage et la courbure du bas du dos. Crédit : Image reproduite avec l’aimable autorisation de Scott Williams, Département d’anthropologie de l’Université de New York.

Une nouvelle analyse examine les différences de colonne vertébrale entre les humains et les Néandertaliens – et l’impact possible de l’industrialisation.

L’examen de la colonne vertébrale de l’homme de Néandertal, un parent éteint de l’espèce humaine, peut expliquer les maux de dos dont souffrent les humains aujourd’hui, a conclu une équipe d’anthropologues dans une nouvelle étude comparative.

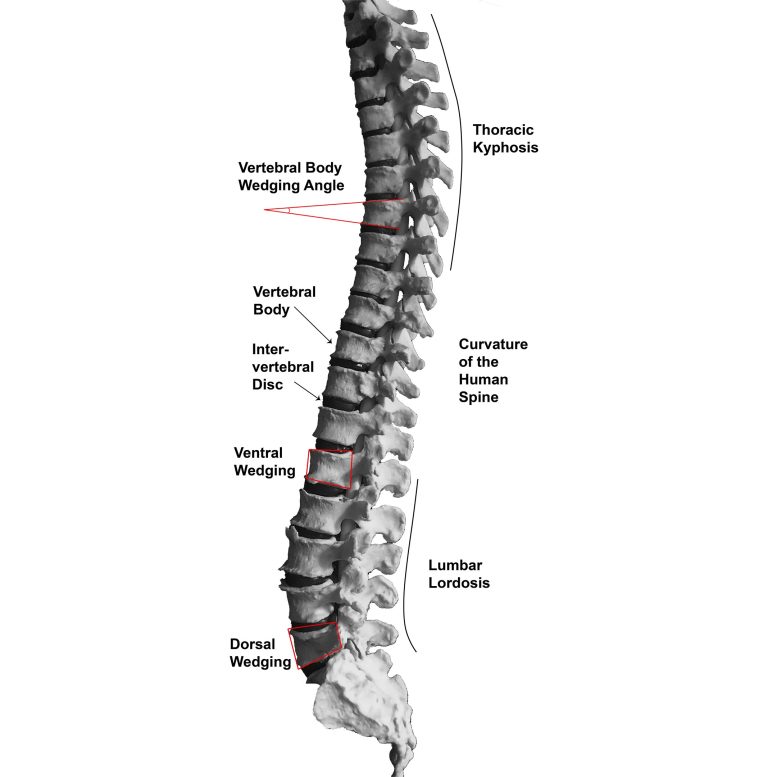

L’analyse se concentre sur la courbure de la colonne vertébrale, qui est causée, en partie, par un coin, ou un angle, des vertèbres et des disques intervertébraux – le matériau plus mou entre les vertèbres.

“Les Néandertaliens ne se distinguent pas des humains modernes en ce qui concerne le calage lombaire et possédaient donc probablement des bas de dos courbés comme nous”, explique Scott Williams, professeur associé en New York University’s Department of Anthropology and one of the authors of the paper, which appears in the journal PNAS Nexus. “However, over time, specifically after the onset of industrialization in the late 19th century, we see increased wedging in the lower back bones of today’s humans—a change that may relate to higher instances of back pain, and other afflictions, in postindustrial societies.”

Contributions to curvature of the modern human spine. Wedging of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs results in thoracic kypohsis and lumbar lordosis. Credit: Image courtesy of Scott Williams, NYU’s Department of Anthropology

Neanderthals have long been thought to have a different posture than modern humans.

“A good part of this perspective derives from the wedging of Neanderthals’ lumbar, or lower, vertebrae—their spines in this region curve less than those of modern humans studied in the U.S. or Europe,” explains Williams.

However, much of this view was based on an analysis of modern humans beginning in the late 19th century—well after the onset of industrialization, which significantly altered our daily lives. Furniture, for instance, became more widely available and desk jobs more prevalent—both of which encouraged sitting and, with it, changes in posture. These changes were coupled with a reduction in high-activity occupations, such as agriculture. In addition, specific afflictions became associated with working conditions that elicit poor posture.

“Past research has shown that higher rates of low back pain are associated with urban areas and especially in ‘enclosed workshop’ settings where employees maintain tedious and painful work postures, such as constantly sitting on stools in a forward leaning position,” Williams observes.

In other words, by examining spines from humans who lived in the post-industrial era, past researchers may have mistakenly concluded that spine formation is due to evolutionary development rather than changed living and working conditions.

To address this possibility, Williams and his colleagues examined both pre-industrial and post-industrial spines of male and female modern humans from around the world—a sample that included more than 300 spines, totaling more than 1,600 vertebrae—along with samples of Neandertal spines.

Overall, they found that spines in post-industrial people showed more lumbar wedging than did those in pre-industrial people. Moreover, Neanderthals’ spines were significantly different from those in post-industrial people but not from pre-industrial people. Notably, the scientists found no differences linked to geography within samples from the same era.

“A pre-industrial vs. post-industrial lifestyle is the important factor,” explains Williams, who acknowledges that because lower back curvature is made up of soft tissues (i.e., intervertebral discs), not just bones, it cannot be ascertained that Neanderthals’ lumbar lordosis differed from modern humans.

“The bones are often all that is preserved in fossils, so it’s all we have to work with,” he adds.

Nonetheless, the distinctions in spine formation between pre-industrial and post-industrial humans offer new insights into back conditions facing many today.

“Diminished physical activity levels, bad posture, and the use of furniture, among other changes in lifestyle that accompanied industrialization, resulted, over time, in inadequate soft tissue structures to support lumbar lordosis during development,” Williams says. “To compensate, our lower-back bones have taken on more wedging than our pre-industrial and Neandertal predecessors, potentially contributing to the frequency of lower back pain we find in post-industrial societies.”

Reference: ” Inferring lumbar lordosis in Neandertals and other hominins” by Scott A Williams, Iris Zeng, Glen J Paton, Christopher Yelverton, ChristiAna Dunham, Kelly R Ostrofsky, Saul Shukman, Monica V Avilez, Jennifer Eyre, Tisa Loewen, Thomas C Prang and Marc R Meyer, 2 March 2022, PNAS Nexus.

DOI: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgab005

The study also included researchers from the University of Johannesburg, Texas A&M University, the New York Institute of Technology, Arizona State University, and Chaffey College, along with Monica Alivez, an NYU doctoral student, and Saul Shukman, an NYU undergraduate student.