Une nouvelle étude d’imagerie cérébrale révèle que les participants qui ont souffert de COVID-19, même léger, ont présenté une réduction moyenne de la taille du cerveau entier.

Les chercheurs n’ont cessé de rassembler des informations importantes sur les effets du COVID-19 on the body and brain. Two years into the pandemic, these findings are raising concerns about the long-term impacts the coronavirus might have on biological processes such as aging.

As a cognitive neuroscientist, I have focused in my past research on understanding how normal brain changes related to aging affect people’s ability to think and move – particularly in middle age and beyond.

But as evidence came in showing that COVID-19 could affect the body and brain for months following infection, my research team shifted some of its focus to better understanding how the illness might influence the natural process of aging. This was motivated in large part by compelling new work from the United Kingdom investigating the impact of COVID-19 on the human brain.

Peering in at the brain’s response to COVID-19

In a large study published in the journal Nature on March 7, 2022, a team of researchers in the UK investigated brain changes in people ages 51 to 81 who had experienced COVID-19. This work provides important new insights about the impact of COVID-19 on the human brain.

In the study, researchers relied on a database called the UK Biobank, which contains brain imaging data from over 45,000 people in the U.K. going back to 2014. This means that there was baseline data and brain imaging of all of those people from before the pandemic.

The research team compared people who had experienced COVID-19 with participants who had not, carefully matching the groups based on age, sex, baseline test date, and study location, as well as common risk factors for disease, such as health variables and socioeconomic status.

The team found marked differences in gray matter – or the neurons that process information in the brain – between those who had been infected with COVID-19 and those who had not. Specifically, the thickness of the gray matter tissue in brain regions known as the frontal and temporal lobes was reduced in the COVID-19 group, differing from the typical patterns seen in the people who hadn’t had a COVID-19 infection.

In the general population, it is normal to see some change in gray matter volume or thickness over time as people age. But the changes were more extensive than normal in those who had been infected with COVID-19.

Interestingly, when the researchers separated the individuals who had severe enough illness to require hospitalization, the results were the same as for those who had experienced milder COVID-19. That is, people who had been infected with COVID-19 showed a loss of brain volume even when the disease was not severe enough to require hospitalization.

Finally, researchers also investigated changes in performance on cognitive tasks and found that those who had contracted COVID-19 were slower in processing information than those who had not. This processing ability was correlated with volume in a region of the brain known as the cerebellum, indicating a link between brain tissue volume and cognitive performance in those with COVID-19.

This study is particularly valuable and insightful because of its large sample sizes both before and after illness in the same people, as well as its careful matching with people who had not had COVID-19.

What do these changes in brain volume mean?

Early on in the pandemic, one of the most common reports from those infected with COVID-19 was the loss of sense of taste and smell.

Some COVID-19 patients have experienced either the loss of, or a reduction in, their sense of smell.

Strikingly, the brain regions that the U.K. researchers found to be affected by COVID-19 are all linked to the olfactory bulb, a structure near the front of the brain that passes signals about smells from the nose to other brain regions. The olfactory bulb has connections to regions of the temporal lobe. Researchers often talk about the temporal lobe in the context of aging and Alzheimer’s disease, because it is where the hippocampus is located. The hippocampus is likely to play a key role in aging, given its involvement in memory and cognitive processes.

The sense of smell is also important to Alzheimer’s research, as some data has suggested that those at risk for the disease have a reduced sense of smell. While it is too early to draw any conclusions about the long-term impacts of COVID-related effects on the sense of smell, investigating possible connections between COVID-19-related brain changes and memory is of great interest – particularly given the regions implicated and their importance in memory and Alzheimer’s disease.

Un aperçu de la façon dont notre odorat est relié à des récepteurs dans le cerveau.

L’étude souligne également un rôle potentiellement important pour le cervelet, une zone du cerveau impliquée dans les processus cognitifs et moteurs, elle aussi est affectée par le vieillissement. Il existe également une nouvelle ligne de travail impliquant le cervelet dans la maladie d’Alzheimer. d’Alzheimer.

L’avenir

Ces nouvelles découvertes soulèvent d’importantes questions qui restent encore sans réponse : Que signifient ces changements cérébraux consécutifs au COVID-19 pour le processus et le rythme du vieillissement ? De plus, le cerveau se remet-il d’une infection virale avec le temps, et dans quelle mesure ?

Ce sont des domaines de recherche actifs et ouverts que nous commençons à aborder dans mon laboratoire, en conjonction avec nos travaux en cours sur le vieillissement du cerveau.

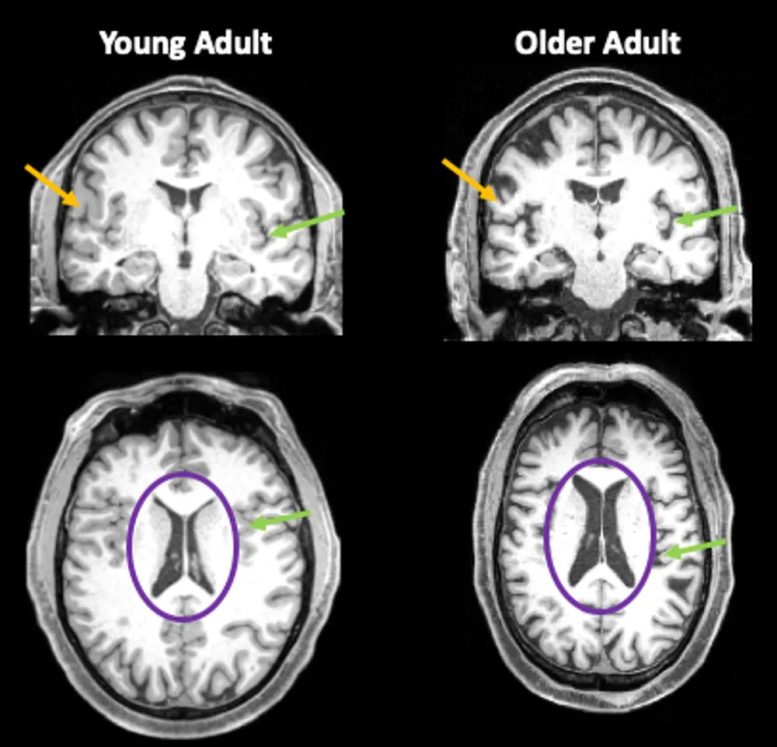

Images du cerveau d’une personne de 35 ans et d’une autre de 85 ans. Les flèches orange montrent la matière grise plus fine chez la personne âgée. Les flèches vertes indiquent les zones où l’espace rempli de liquide céphalo-rachidien (LCR) est plus important en raison de la réduction du volume du cerveau. Les cercles violets mettent en évidence les ventricules du cerveau, qui sont remplis de LCR. Chez les personnes âgées, ces zones remplies de liquide sont beaucoup plus grandes. Crédit : Jessica Bernard

Les travaux de notre laboratoire démontrent qu’avec l’âge, le cerveau pense et s’adapte à l’environnement. traite l’information différemment. En outre, nous avons observé des changements au fil du temps dans la façon dont le corps des gens bouge et comment les gens apprennent de nouvelles habiletés motrices. Plusieurs sites décennies de travail ont démontré que les adultes âgés ont plus de mal à traiter et à manipuler l’information – par exemple à mettre à jour une liste d’épicerie mentale – mais qu’ils conservent généralement leur connaissance des faits et du vocabulaire. En ce qui concerne les capacités motrices, nous savons que les adultes plus âgés apprennent encoremais ils le font plus plus lentement que les jeunes adultes.

En ce qui concerne la structure du cerveau, nous constatons généralement une diminution de la taille du cerveau chez les adultes de plus de 65 ans. Cette diminution n’est pas seulement localisée dans une région. Des différences peuvent être observées dans de nombreuses régions du cerveau. On observe aussi généralement une augmentation du liquide céphalo-rachidien qui remplit l’espace en raison de la perte de tissu cérébral. En outre, la matière blanche, l’isolant des axones – longs câbles qui transportent les impulsions électriques entre les cellules nerveuses – est également moins intacte chez les personnes âgées .

L’espérance de vie a augmentéau cours des dernières décennies. L’objectif est de permettre à tous de vivre longtemps et en bonne santé, mais même dans le meilleur des cas où l’on vieillit sans maladie ni handicap, l’âge adulte entraîne des changements dans la façon de penser et de bouger.

Apprendre comment toutes ces pièces du puzzle s’assemblent nous aidera à percer les mystères du vieillissement afin de contribuer à améliorer la qualité de vie et le fonctionnement des personnes âgées. Et maintenant, dans le contexte de COVID-19, cela nous aidera à comprendre dans quelle mesure le cerveau peut également se rétablir après une maladie.

Rédigé par Jessica Bernard, professeur associé, Texas A&M University.