Petit clip de la simulation Thesan. Voir la vidéo dans l’article ci-dessous.

Nommée d’après une déesse de l’aube, la simulation Thesan du premier milliard d’années aide à expliquer comment le rayonnement a façonné l’univers primitif.

Tout a commencé il y a environ 13,8 milliards d’années par un grand “bang” cosmologique qui a donné naissance à l’univers de manière soudaine et spectaculaire. Peu de temps après, l’univers naissant s’est refroidi de façon spectaculaire et est devenu complètement noir.

Puis, quelques centaines de millions d’années après le Big Bang, the universe woke up, as gravity gathered matter into the first stars and galaxies. Light from these first stars turned the surrounding gas into a hot, ionized plasma — a crucial transformation known as cosmic reionization that propelled the universe into the complex structure that we see today.

Now, scientists can get a detailed view of how the universe may have unfolded during this pivotal period with a new simulation, known as Thesan, developed by scientists at MIT, Harvard University, and the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics.

Named after the Etruscan goddess of the dawn, Thesan is designed to simulate the “cosmic dawn,” and specifically cosmic reionization, a period which has been challenging to reconstruct, as it involves immensely complicated, chaotic interactions, including those between gravity, gas, and radiation.

The Thesan simulation resolves these interactions with the highest detail and over the largest volume of any previous simulation. It does so by combining a realistic model of galaxy formation with a new algorithm that tracks how light interacts with gas, along with a model for cosmic dust.

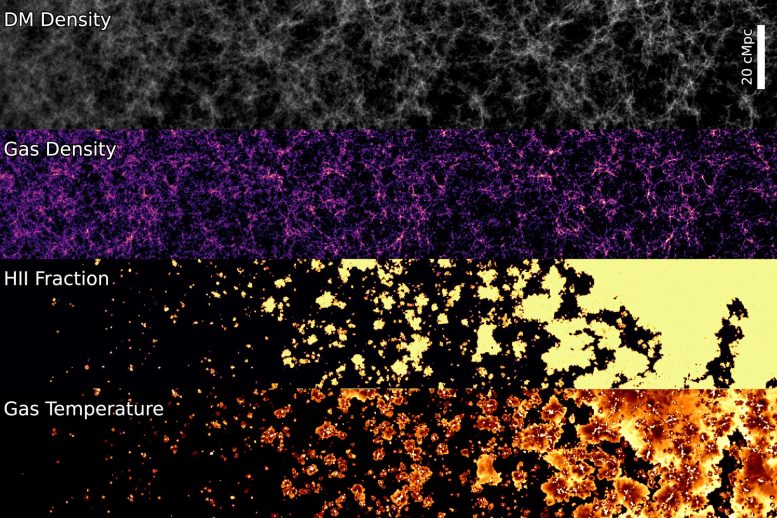

Evolution of simulated properties in the main Thesan run. Time progresses from left to right. The dark matter (top panel) collapse in the cosmic web structure, composed of clumps (haloes) connected by filaments, and the gas (second panel from the top) follows, collapsing to create galaxies. These produce ionizing photons that drive cosmic reionization (third panel from the top), heating up the gas in the process (bottom panel). Credit: Courtesy of THESAN Simulations

With Thesan, the researchers can simulate a cubic volume of the universe spanning 300 million light years across. They run the simulation forward in time to track the first appearance and evolution of hundreds of thousands of galaxies within this space, beginning around 400,000 years after the Big Bang, and through the first billion years.

So far, the simulations align with what few observations astronomers have of the early universe. As more observations are made of this period, for instance with the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope, Thesan may help to place such observations in cosmic context.

For now, the simulations are starting to shed light on certain processes, such as how far light can travel in the early universe, and which galaxies were responsible for reionization.

“Thesan acts as a bridge to the early universe,” says Aaron Smith, a NASA Einstein Fellow in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “It is intended to serve as an ideal simulation counterpart for upcoming observational facilities, which are poised to fundamentally alter our understanding of the cosmos.”

Smith and Mark Vogelsberger, associate professor of physics at MIT, Rahul Kannan of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and Enrico Garaldi at Max Planck have introduced the Thesan simulation through three papers, the third published on March 24, 2022, in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow the light

In the earliest stages of cosmic reionization, the universe was a dark and homogenous space. For physicists, the cosmic evolution during these early “dark ages” is relatively simple to calculate.

“In principle you could work this out with pen and paper,” Smith says. “But at some point gravity starts to pull and collapse matter together, at first slowly, but then so quickly that calculations become too complicated, and we have to do a full simulation.”

To fully simulate cosmic reionization, the team sought to include as many major ingredients of the early universe as possible. They started off with a successful model of galaxy formation that their groups previously developed, called Illustris-TNG, which has been shown to accurately simulate the properties and populations of evolving galaxies. They then developed a new code to incorporate how the light from galaxies and stars interact with and reionize the surrounding gas — an extremely complex process that other simulations have not been able to accurately reproduce at large scale.

“Thesan follows how the light from these first galaxies interacts with the gas over the first billion years and transforms the universe from neutral to ionized,” Kannan says. “This way, we automatically follow the reionization process as it unfolds.”

Finally, the team included a preliminary model of cosmic dust — another feature that is unique to such simulations of the early universe. This early model aims to describe how tiny grains of material influence the formation of galaxies in the early, sparse universe.

La simulation Thesan de l’évolution du gaz et du rayonnement montre le rendu du gaz d’hydrogène neutre. Les couleurs représentent la densité et la luminosité, révélant la structure de la réionisation au sein d’un réseau de filaments de gaz neutre à haute densité.

Pont cosmique

Une fois les ingrédients de la simulation en place, l’équipe a défini ses conditions initiales pour environ 400 000 ans après le Big Bang, en se basant sur des mesures précises de la lumière résiduelle du Big Bang. Elle a ensuite fait évoluer ces conditions dans le temps pour simuler une partie de l’univers, en utilisant la machine SuperMUC-NG – l’un des plus grands superordinateurs au monde – qui a exploité simultanément 60 000 cœurs de calcul pour effectuer les calculs de Thesan pendant l’équivalent de 30 millions d’heures de CPU (un effort qui aurait pris 3 500 ans sur un seul ordinateur de bureau).

Les simulations ont produit la vue la plus détaillée de la réionisation cosmique, à travers le plus grand volume d’espace, de toutes les simulations existantes. Bien que certaines simulations modélisent de grandes distances, elles le font à une résolution relativement faible, tandis que d’autres simulations plus détaillées ne couvrent pas de grands volumes.

“Nous faisons le pont entre ces deux approches : Nous avons à la fois un grand volume et une haute résolution”, souligne M. Vogelsberger.

Les premières analyses des simulations suggèrent que vers la fin de la réionisation cosmique, la distance que la lumière était capable de parcourir a augmenté de façon plus spectaculaire que ce que les scientifiques avaient précédemment supposé.

“Thesan a découvert que la lumière ne parcourt pas de grandes distances au début de l’univers”, explique Kannan. “En fait, cette distance est très faible, et ne devient importante qu’à la toute fin de la réionisation, augmentant d’un facteur 10 en seulement quelques centaines de millions d’années.”

Les chercheurs voient également des indices sur le type de galaxies responsables de la réionisation. La masse d’une galaxie semble influencer la réionisation, mais l’équipe affirme que d’autres observations, réalisées par James Webb et d’autres observatoires, aideront à identifier les galaxies prédominantes.

“Il y a beaucoup d’éléments mobiles dans le processus de réionisation. [modeling cosmic reionization]conclut Vogelsberger. “Lorsque nous pouvons rassembler tout cela dans une sorte de machine et commencer à la faire fonctionner et qu’elle produit un univers dynamique, c’est pour nous tous un moment assez gratifiant.”

Référence : “Le projet thesan : Lyman-a emission and transmission during the Epoch of Reionization” par A Smith, R Kannan, E Garaldi, M Vogelsberger, R Pakmor, V Springel et L Hernquist, 24 mars 2022, Notices mensuelles de la Société royale d’astronomie.

DOI : 10.1093/mnras/stac713

Cette recherche a été soutenue en partie par la NASA, la National Science Foundation et le Gauss Center for Supercomputing.