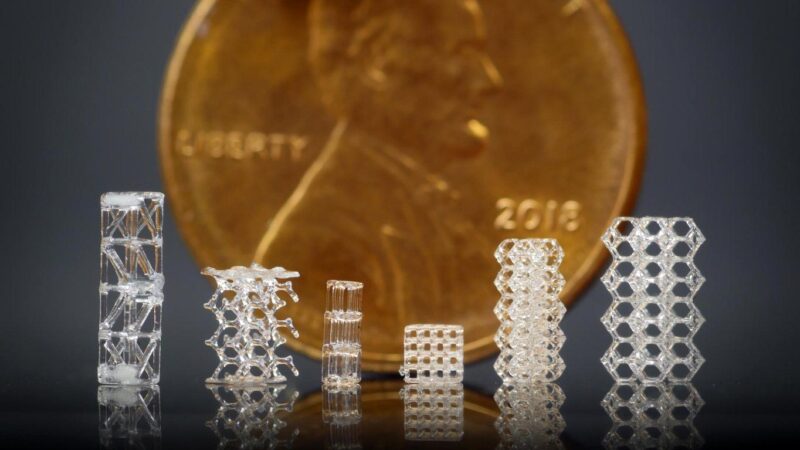

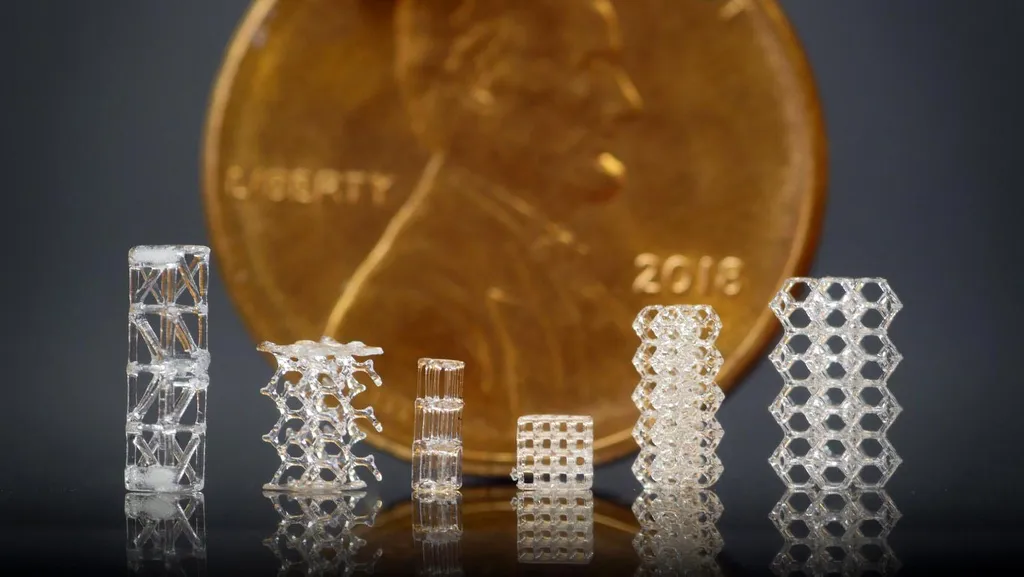

Des chercheurs de l’université de Berkeley ont mis au point une nouvelle méthode d’impression en 3D de microstructures en verre, dont ces treillis de verre imprimés en 3D, qui sont présentés devant un penny américain pour l’échelle. Crédit : Photo de Joseph Toombs/UC Berkeley

Cette technique de fabrication permet une production plus rapide, une meilleure qualité optique et une plus grande souplesse de conception.

Les chercheurs de l’University of California, Berkeley have developed a new way to 3D-print glass microstructures that is faster and produces objects with higher optical quality, design flexibility, and strength, according to a new study published in the journal Science.

A 3D-printed, trifurcated microtubule model. Credit: Video by Adam Lau/Berkeley Engineering

Working with scientists from the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg in Germany, the researchers extended the capabilities of a 3D-printing process they developed three years ago — computed axial lithography (CAL) — to print much finer features and to print in glass. They dubbed this new system “micro-CAL.”

Glass is often the preferred material for creating complicated microscopic objects, including lenses in compact, high-quality cameras used in smartphones and endoscopes, as well as microfluidic devices used to analyze or process minute amounts of liquid. However, present manufacturing methods can be slow, expensive, and limited in their ability to meet the industry’s increasing demands.

The CAL process is fundamentally different from today’s industrial 3D-printing manufacturing processes, which build up objects from thin layers of material. This technique can be time-intensive and result in rough surface texture. CAL, however, 3D-prints the entire object simultaneously. Researchers use a laser to project patterns of light into a rotating volume of light-sensitive material, building up a 3D light dose that then solidifies in the desired shape. The layer-less nature of the CAL process enables smooth surfaces and complex geometries.

This study pushes the boundaries of CAL to demonstrate its ability to print microscale features in glass structures. “When we first published this method in 2019, CAL could print objects into polymers with features down to about a third of a millimeter in size,” said Hayden Taylor, principal investigator and professor of mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley.

“Now, with micro-CAL, we can print objects in polymers with features down to about 20 millionths of a meter, or about a quarter of a human hair’s breadth. And for the first time, we have shown how this method can print not only into polymers but also into glass, with features down to about 50 millionths of a meter.”

Researchers at UC Berkeley have developed a new way to 3D print intricate glass microstructures, including this tetrakaidecahedron lattice structure. Credit: Photo by Adam Lau/UC Berkeley

To print the glass, Taylor and his research team collaborated with scientists from the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg, who have developed a special resin material containing nanoparticles of glass surrounded by a light-sensitive binder liquid. Digital light projections from the printer solidify the binder, then the researchers heat the printed object to remove the binder and fuse the particles together into a solid object of pure glass.

“The key enabler here is that the binder has a refractive index that is virtually identical to that of the glass, so that light passes through the material with virtually no scattering,” said Taylor. “The CAL printing process and this Glassomer [GmbH]-développés sont parfaitement compatibles les uns avec les autres.”

Micrographie électronique à balayage d’un réseau cubique avec des éléments de réseau de 20 micromètres. Crédit : Photo de Joseph Toombs/UC Berkeley

L’équipe de recherche, dont fait partie l’auteur principal Joseph Toombs, étudiant en doctorat dans le laboratoire de Taylor, a également effectué des tests et découvert que les objets en verre imprimés par CAL avaient une résistance plus constante que ceux fabriqués à l’aide d’un processus d’impression conventionnel à base de couches. “Les objets en verre ont tendance à se briser plus facilement lorsqu’ils présentent davantage de défauts ou de fissures, ou que leur surface est rugueuse”, a expliqué M. Taylor. “La capacité de CAL à fabriquer des objets avec des surfaces plus lisses que d’autres procédés d’impression 3D basés sur des couches constitue donc un gros avantage potentiel.”

Joseph Toombs, étudiant diplômé de l’UC Berkeley, utilise des pinces pour ramasser une structure en treillis de verre qui a été créée à l’aide d’une nouvelle technique innovante d’impression 3D. Crédit : Photo par Adam Lau/UC Berkeley

La méthode d’impression 3D CAL offre aux fabricants d’objets en verre microscopiques un moyen nouveau et plus efficace de répondre aux exigences des clients en matière de géométrie, de taille et de propriétés optiques et mécaniques. Il s’agit notamment des fabricants de composants optiques microscopiques, qui constituent un élément clé des appareils photo compacts, des casques de réalité virtuelle, des microscopes de pointe et d’autres instruments scientifiques. “La possibilité de fabriquer ces composants plus rapidement et avec une plus grande liberté géométrique pourrait conduire à de nouvelles fonctions ou à des produits moins coûteux”, a déclaré M. Taylor.

Référence : “Volumetric additive manufacturing of silica glass with microscale computed axial lithography” par Joseph T. Toombs, Manuel Luitz, Caitlyn C. Cook, Sophie Jenne, Chi Chung Li, Bastian E. Rapp, Frederik Kotz-Helmer et Hayden K. Taylor, 14 avril 2022, Science.

DOI : 10.1126/science.abm6459

Cette étude a été financée par la National Science Foundation, le Conseil européen de la recherche, la Fondation Carl Zeiss, la Fondation allemande de la recherche et le Département américain de l’énergie.