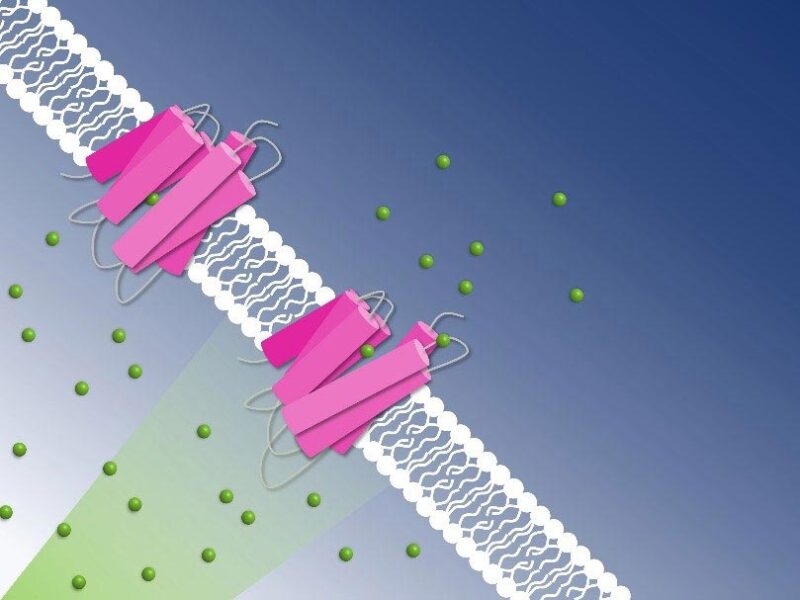

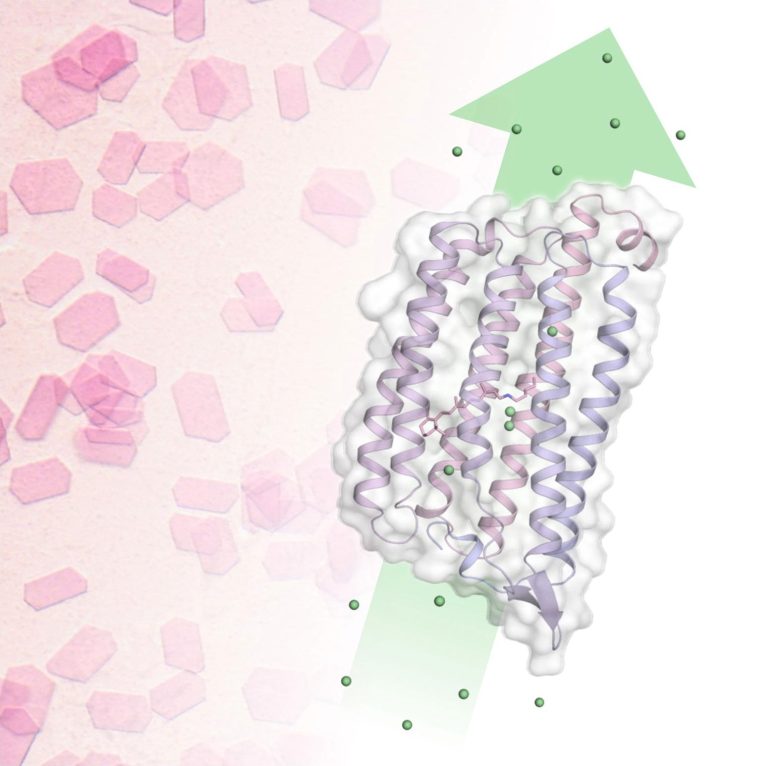

Pompage photoactif du chlorure à travers la membrane cellulaire, capturé par cristallographie sérielle à résolution temporelle : Les ions chlorure (sphères vertes) sont transportés à travers la membrane cellulaire par la pompe à chlorure du NmHR (rose). Crédit : Guillaume Gotthard, Sandra Mous

Pour la première fois, un film moléculaire a capturé en détail le processus de transport d’un anion à travers la membrane cellulaire par une pompe protéique alimentée par la lumière. Publié dans Science, les chercheurs ont élucidé le mystère de la manière dont l’énergie lumineuse déclenche le processus de pompage – et comment la nature s’est assurée qu’il n’y ait pas de fuite d’anions vers l’extérieur.

De nombreuses bactéries et algues unicellulaires possèdent des pompes actionnées par la lumière dans leurs membranes cellulaires : des protéines qui changent de forme lorsqu’elles sont exposées à des photons, de sorte qu’elles peuvent transporter des atomes chargés à l’intérieur ou à l’extérieur de la cellule. Grâce à ces pompes, leurs propriétaires unicellulaires peuvent s’adapter à la valeur du pH ou à la salinité de l’environnement.

Une de ces bactéries est Nonlabens marinusdécouverte pour la première fois en 2012 dans l’océan Pacifique. Elle possède, entre autres, une protéine rhodopsine dans sa membrane cellulaire qui transporte les anions de chlorure de l’extérieur de la cellule vers son intérieur. Tout comme dans l’œil humain, une molécule de rétine liée à la protéine s’isomérise lorsqu’elle est exposée à la lumière. Cette isomérisation déclenche le processus de pompage. Les chercheurs ont maintenant acquis une connaissance détaillée du fonctionnement de la pompe à chlorure dans la cellule. Nonlabens marinus fonctionne.

L’étude a été menée par Przemyslaw Nogly, autrefois postdoc au PSI et maintenant boursier Ambizione et chef de groupe à l’ETH Zürich. Avec son équipe, il a combiné des expériences dans deux des grandes installations de recherche du PSI, la Source de Lumière Suisse SLS and the X-ray free-electron laser SwissFEL. Slower dynamics in the millisecond-range were investigated via time-resolved serial crystallography at SLS while faster, up to picosecond, events were captured at SwissFEL – then both sets of data were put together.

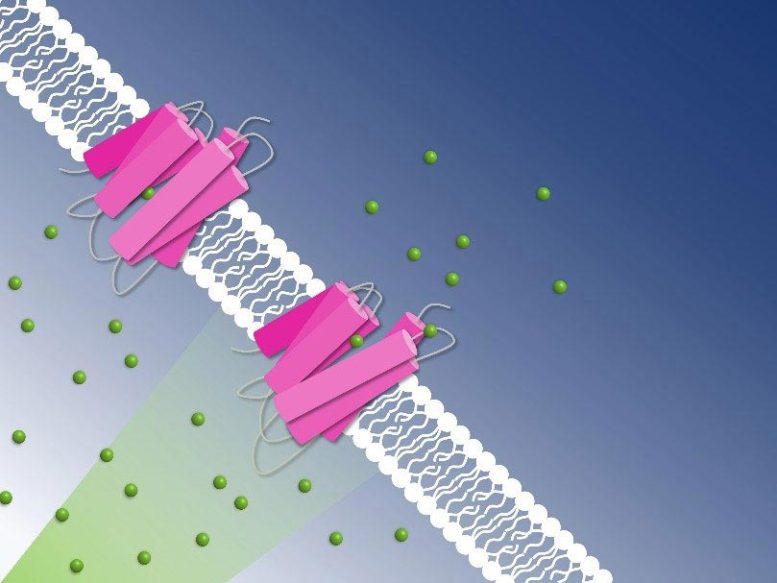

Pink crystals reveal the mechanism of chloride transport over the cell membrane: Using time-resolved serial crystallography, the pink NmHR crystals revealed ion binding sites in the chloride transporter and pumping dynamics after photoactivation. This allowed researchers to decipher the chloride transport mechanism. Credit: Sandra Mous

“In one paper, we exploit the advantages of two state-of-the-art facilities to tell the full story of this chloride pump,” Nogly says. Jörg Standfuss, co-author of the study who built up a PSI team dedicated to creating such molecular movies, adds: “This combination enables first-class biological research as would only be possible at very few other places in the world beside PSI.”

No backflow

As the study has revealed, the chloride anion is attracted by a positively charged patch of the rhodopsin protein in Nonlabens marinus’ cell membrane. Here, the anion enters the protein and finally binds to a positive charge at the retinal molecule inside. When retinal isomerizes due to light exposure and flips over, it drags the chloride anion along and thus transports it a bit further inside the protein. “This is how light energy is directly converted into kinetic energy, triggering the very first step of the ion transport,” Sandra Mous says, a PhD student in Nogly’s group and first author of the paper.

Being on the other side of the retinal molecule now, the chloride ion has reached a point of no return. From here, it goes only further inside the cell. An amino acid helix also relaxes when chloride moves along, additionally obstructing the passage back outside. “During the transport, two molecular gates thus make sure that chloride only moves in one direction: inside,” Nogly says. One pumping process in total takes about 100 milliseconds.

Two years ago, Jörg Standfuss, Przemyslaw Nogly and their team unravelled the mechanism of another light-driven bacterial pump: the sodium pump of Krokinobacter eikastus. Researchers are eager to discover the details of light-driven pumps because these proteins are valuable optogenetic tools: genetically engineered into mammalian neurons, they make it possible to control the neurons activities by light and thus research their function.

Reference: “Dynamics and mechanism of a light-driven chloride pump” by Sandra Mous, Guillaume Gotthard, David Ehrenberg, Saumik Sen, Tobias Weinert, Philip J. M. Johnson, Daniel James, Karol Nass, Antonia Furrer, Demet Kekilli, Pikyee Ma, Steffen Brünle, Cecilia Maria Casadei, Isabelle Martiel, Florian Dworkowski, Dardan Gashi, Petr Skopintsev, Maximilian Wranik, Gregor Knopp, Ezequiel Panepucci, Valerie Panneels, Claudio Cirelli, Dmitry Ozerov, Gebhard Schertler, Meitian Wang, Chris Milne, Joerg Standfuss, Igor Schapiro, Joachim Heberle and Przemyslaw Nogly, 3 February 2022, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abj6663