Les scientifiques qui étudient le vaccin Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) contre la tuberculose ont découvert qu’il induit des changements spécifiques dans les métabolites et les lipides qui sont en corrélation avec les réponses du système immunitaire inné. Cette découverte fournit des pistes pour rendre d’autres vaccins plus efficaces chez les populations vulnérables ayant des systèmes immunitaires distincts.

Des chercheurs découvrent des changements dans les profils de métabolites et de lipides, fournissant des indices pour la conception de futurs vaccins pour les nouveau-nés.

Le vaccin centenaire Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) contre la tuberculose est l’un des vaccins les plus anciens et les plus répandus au monde, utilisé pour immuniser 100 millions de nouveau-nés chaque année. Administré dans les pays où la tuberculose est endémique, il s’est avéré, de manière surprenante, qu’il protégeait les nouveau-nés et les jeunes nourrissons contre de multiples infections bactériennes et virales sans rapport avec la tuberculose. Il existe même des preuves qu’il peut réduire la gravité de COVID-19.

What’s special about BCG vaccine? How does it protect infants so broadly? It turns out little is known. To understand its mechanism of action, researchers at the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital partnered with the Expanded Program on Immunization Consortium (EPIC), an international team studying early life immunization, to collect and comprehensively profile blood samples from newborns immunized with BCG, using a powerful “big data” approach.

Their study, which will be published online today (May 3, 2022) in the journal Cell Reports, found that the BCG vaccine induces specific changes in metabolites and lipids that correlate with innate immune system responses. The findings provide clues toward making other vaccines more effective in vulnerable populations with distinct immune systems, such as newborns.

Small babies, big data

First author Joann Diray Arce, PhD, and her colleagues began with blood samples from low-birthweight newborns in Guinea Bissau who were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial to receive BCG either at birth or after a delay of six weeks. Both groups had small blood samples taken at four weeks (after BCG was given to the first group, and before it was given to the second group).

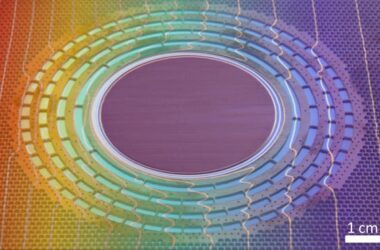

Using metabolomics and lipidomics, the team comprehensively profiled the impact of BCG immunization on the newborns’ blood plasma. They found that BCG vaccines given at birth changed metabolite and lipid profiles in newborns’ blood plasma in a pattern distinct from those in the delayed-vaccine group. The changes correlated with changes in cytokine production, a key feature of innate immunity.

The researchers had parallel findings when they tested BCG in cord blood samples from a cohort of Boston newborns and samples from a separate NIH/NIAID-funded Human Immunology Project Consortium study of newborns in The Gambia and Papua New Guinea.

“We now have some lipid and metabolic biomarkers of vaccine protection that we can test and manipulate in mouse models,” says Arce. “We studied three different BCG formulations and showed that they converge on similar pathways of interest. Reshaping of the metabolome by BCG may contribute to the molecular mechanisms of a newborn’s immune response.”

“A growing number of studies show that BCG vaccine protects against unrelated infections,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program and the study’s senior investigator. “It’s critical that we learn from BCG to better understand how to protect newborns. BCG is an ‘old school’ vaccine — it’s made from a live, weakened germ — but live vaccines like BCG seem to activate the immune system in a very different way in early life, providing broad protection against a range of bacterial and viral infections. There’s much work ahead to better understand that and use that information to build better vaccines for infants.”

Reference: 3 May 2022, Cell Reports.

DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110772

The study was supported by the NIAID (U19AI118608, U01 AI124284), the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, and the Mueller Health Foundation. Levy is a named inventor on several Boston Children’s Hospital patents relating to human microphysiologic assay systems and vaccine adjuvants. Coauthors Scott McCulloch and Greg Michelotti are employees of Metabolon Inc. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.