Il est possible d’élargir son esprit en réfléchissant à ce qu’il y a vraiment là-bas.

Juste au-dessus de vous se trouve le ciel – ou comme les scientifiques l’appellent, l’atmosphère. Elle s’étend sur environ 32 kilomètres (20 miles) au-dessus de la Terre. Flottant autour de l’atmosphère est un mélange de molécules – de minuscules morceaux d’air si petits que vous en absorbez des milliards à chaque fois que vous respirez.

Au-dessus de l’atmosphère se trouve l’espace. On l’appelle ainsi parce qu’il contient beaucoup moins de molécules, avec beaucoup d’espace vide entre elles.

T’es-tu déjà demandé ce que cela ferait de voyager dans l’espace – et de continuer ? Que trouveriez-vous ? Des scientifiques comme moi sont capables d’expliquer une grande partie de ce que tu verrais. Mais il y a des choses que nous ne savons pas encore, comme par exemple si l’espace est éternel.

Planètes, étoiles et galaxies

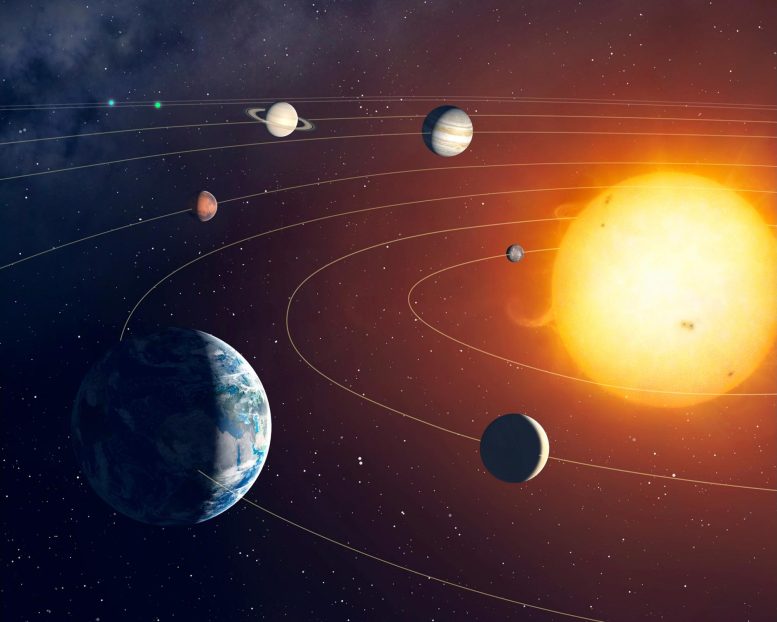

Au début de votre voyage dans l’espace, vous reconnaîtrez peut-être certaines vues. Le site Terre fait partie d’un groupe de planètes qui tournent toutes autour du Soleil – avec quelques astéroïdes et comètes en orbite, également.

Un voisinage familier.

Vous savez peut-être que le Soleil n’est en fait qu’une étoile moyenne, et qu’il semble plus grand et plus brillant que les autres étoiles… seulement parce qu’il est plus proche. Pour atteindre l’étoile la plus proche, il faudrait traverser des billions de kilomètres d’espace. Si vous pouviez monter à bord de la sonde spatiale la plus rapide ;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>NASA has ever made, it would still take you thousands of years to get there.

If stars are like houses, then galaxies are like cities full of houses. Scientists estimate there are 100 billion stars in Earth’s galaxy. If you could zoom out, way beyond Earth’s galaxy, those 100 billion stars would blend together – the way lights of city buildings do when viewed from an airplane.

Recently astronomers have learned that many or even most stars have their own orbiting planets. Some are even like Earth, so it’s possible they might be home to other beings also wondering what’s out there.

This packed image taken with the Hubble Space Telescope showcases the galaxy cluster ACO S 295, as well as a jostling crowd of background galaxies and foreground stars. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, F. Pacaud, D. Coe

You would have to travel through millions of trillions more miles of space just to reach another galaxy. Most of that space is almost completely empty, with only some stray molecules and tiny mysterious invisible particles scientists call “dark matter.”

Using big telescopes, astronomers see millions of galaxies out there – and they just keep going, in every direction.

If you could watch for long enough, over millions of years, it would look like new space is gradually being added between all the galaxies. You can visualize this by imagining tiny dots on a deflated balloon and then thinking about blowing it up. The dots would keep moving farther apart, just like the galaxies are.

Is there an end?

If you could keep going out, as far as you wanted, would you just keep passing by galaxies forever? Are there an infinite number of galaxies in every direction? Or does the whole thing eventually end? And if it does end, what does it end with?

These are questions scientists don’t have definite answers to yet. Many think it’s likely you would just keep passing galaxies in every direction, forever. In that case, the universe would be infinite, with no end.

Some scientists think it’s possible the universe might eventually wrap back around on itself – so if you could just keep going out, you would someday come back around to where you started, from the other direction.

One way to think about this is to picture a globe, and imagine that you are a creature that can move only on the surface. If you start walking any direction, east for example, and just keep going, eventually you would come back to where you began. If this were the case for the universe, it would mean it is not infinitely big – although it would still be bigger than you can imagine.

In either case, you could never get to the end of the universe or space. Scientists now consider it unlikely the universe has an end – a region where the galaxies stop or where there would be a barrier of some kind marking the end of space.

But nobody knows for sure. How to answer this question will need to be figured out by a future scientist.

Written by Jack Singal, Associate Professor of Physics, University of Richmond.