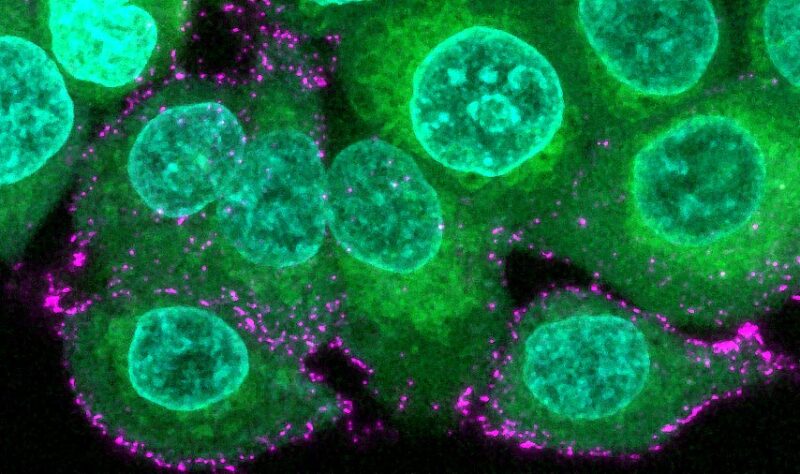

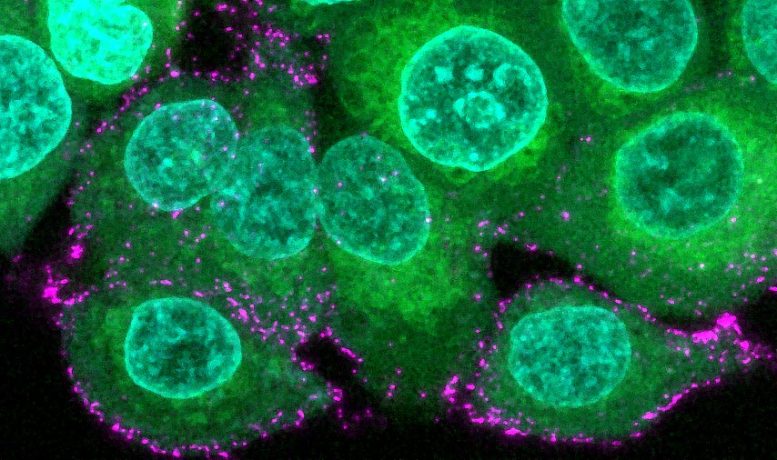

Image de cellules épithéliales humaines (vertes avec des noyaux bleus) incubées avec des virions synthétiques SARS-CoV-2 (magenta) pour étudier l’infection et l’évasion immunitaire. Crédit : Oskar Staufer et MPI pour la recherche médicale, Allemagne.

Une nouvelle recherche montre que le virus joue un jeu de “cache-cache” avec le système immunitaire.

Les personnes souffrant de COVID-19 could have several different SARS-CoV-2 variants hidden away from the immune system in different parts of the body, finds new research published in Nature Communications by an international research team. The study’s authors say that this may make complete clearance of the virus from the body of an infected person, by their own antibodies, or by therapeutic antibody treatments, much more difficult.

COVID-19 continues to sweep the globe causing hospitalizations and deaths, damaging communities and economies worldwide. Successive variants of concern (VoC), replaced the original virus from Wuhan, increasingly escaping immune protection offered by vaccination or antibody treatments.

In new research, comprising two studies published in parallel in Nature Communications, an international team led by Professor Imre Berger at the University of Bristol and Professor Joachim Spatz at the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, both Directors of the Max Planck Bristol Centre of Minimal Biology, show how the virus can evolve distinctly in different cell types, and adapt its immunity, in the same infected host.

Structure de la protéine spike de BrisDelta, une variante précoce du SRAS-CoV-2 découverte à Bristol. Crédit : Christine Toelzer, Université de Bristol.

L’équipe a cherché à étudier la fonction d’une poche sur mesure dans la protéine spike du SRAS-CoV-2 dans le cycle d’infection du virus. La poche, découverte par l’équipe de Bristol lors d’une étude de l’impact de l’infection par le virus sur le cycle d’infection. percée antérieurejouait un rôle essentiel dans l’infectivité virale.

“Une série incessante de variants a complètement remplacé le virus original à l’heure actuelle, Omicron et Omicron 2 dominant dans le monde entier”, a déclaré le professeur Imre Berger. “Nous avons analysé une variante précoce découverte à Bristol, BrisDelta. Elle avait changé de forme par rapport au virus original, mais la poche que nous avions découverte était là, inchangée.” Fait intriguant, BrisDelta se présente comme une petite sous-population dans les échantillons prélevés chez les patients, mais semble infecter certains types de cellules mieux que le virus qui a dominé la première vague d’infections.

Le Dr Kapil Gupta, auteur principal de l’étude BrisDelta, explique : “Nos résultats ont montré que l’on peut avoir plusieurs variantes différentes du virus dans son corps. Certains de ces variants peuvent utiliser les cellules des reins ou de la rate comme niche pour se cacher, pendant que l’organisme est occupé à se défendre contre le type de virus dominant. Il pourrait donc être difficile pour les patients infectés de se débarrasser entièrement du SRAS-CoV-2.”

L’équipe a appliqué des techniques de biologie synthétique de pointe, une imagerie de pointe et l’informatique en nuage pour déchiffrer les mécanismes viraux à l’œuvre. Pour comprendre la fonction de la poche, les scientifiques ont construit en éprouvette des virions synthétiques du SRAS-CoV-2, qui imitent le virus mais présentent l’avantage majeur d’être sans danger, car ils ne se multiplient pas dans les cellules humaines.

En utilisant ces virions artificiels, ils ont pu étudier le mécanisme exact de la poche dans l’infection virale. Ils ont démontré que lors de la liaison d’un acid, the spike protein decorating the virions changed their shape. This switching ‘shape’ mechanism effectively cloaks the virus from the immune system.

Dr. Oskar Staufer, lead author of this study and joint member of the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg and the Max Planck Centre in Bristol, explains: “By ‘ducking down’ of the spike protein upon binding of inflammatory fatty acids, the virus becomes less visible to the immune system. This could be a mechanism to avoid detection by the host and a strong immune response for a longer period of time and increase total infection efficiency.”

“It appears that this pocket, specifically built to recognize these fatty acids, gives SARS-CoV-2 an advantage inside the body of infected people, allowing it to multiply so fast. This could explain why it is there, in all variants, including Omicron” added Professor Berger. “Intriguingly, the same feature also provides us with a unique opportunity to defeat the virus, exactly because it is so conserved — with a tailormade antiviral molecule that blocks the pocket.” Halo Therapeutics, a recent University of Bristol spin-out founded by the authors, pursues exactly this approach to develop pocket-binding pan-coronavirus antivirals.

References:

“Structural insights in cell-type specific evolution of intra-host diversity by SARS-CoV-2” by Kapil Gupta, Christine Toelzer, Maia Kavanagh Williamson, Deborah K. Shoemark, A. Sofia F. Oliveira, David A. Matthews, Abdulaziz Almuqrin, Oskar Staufer, Sathish K. N. Yadav, Ufuk Borucu, Frederic Garzoni, Daniel Fitzgerald, Joachim Spatz, Adrian J. Mulholland, Andrew D. Davidson, Christiane Schaffitzel and Imre Berger, 11 January 2022, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-27881-6

“Synthetic virions reveal fatty acid-coupled adaptive immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein” by Oskar Staufer, Kapil Gupta, Jochen Estebano Hernandez Bücher, Fabian Kohler, Christian Sigl, Gunjita Singh, Kate Vasileiou, Ana Yagüe Relimpio, Meline Macher, Sebastian Fabritz, Hendrik Dietz, Elisabetta Ada Cavalcanti Adam, Christiane Schaffitzel, Alessia Ruggieri, Ilia Platzman, Imre Berger and Joachim P. Spatz, 14 February 2022, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-28446-x

“Free fatty acid binding pocket in the locked structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein” by Christine Toelzer, Kapil Gupta, Sathish K. N. Yadav, Ufuk Borucu, Andrew D. Davidson, Maia Kavanagh Williamson, Deborah K. Shoemark, Frederic Garzoni, Oskar Staufer, Rachel Milligan, Julien Capin, Adrian J. Mulholland, Joachim Spatz, Daniel Fitzgerald, Imre Berger and Christiane Schaffitzel, 21 September 2020, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abd3255

The team included experts from Bristol UNCOVER Group, the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, Germany, Bristol University spin-out Halo Therapeutics Ltd and further collaborators in UK and in Germany. The studies were supported by funds from the Max Planck Gesellschaft, the Wellcome Trust and the European Research Council, with additional support from Oracle for Research for high-performance cloud computing resources. The authors are grateful for the generous support by the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute of the University of Bristol.