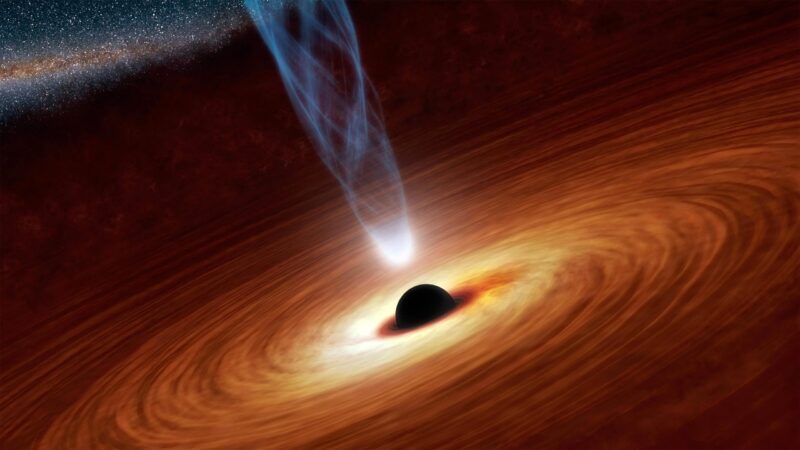

Illustration conceptuelle d’un trou noir supermassif émettant un jet de rayons X. Crédit : NASA/JPL-Caltech

Fin 2018, l’observatoire des ondes gravitationnelles, LIGO, a annoncé avoir détecté la source la plus lointaine et la plus massive d’ondes gravitationnelles. ondulations de l’espace-temps jamais observée : ondes gravitationnelles déclenchées par des paires de trous noirs entrant en collision dans l’espace lointain. Ce n’est que depuis 2015 que nous sommes en mesure d’observer ces corps astronomiques invisibles, qui ne pouvaient alors être détectés que par leur attraction gravitationnelle. Puis, lors d’une percée en 2019, le télescope Event Horizon a capturé un… image d’un trou noir et de son ombre pour la première fois.

L’histoire de notre chasse à ces objets énigmatiques remonte au 18e siècle, mais la phase cruciale s’est déroulée pendant une période sombre de l’histoire de l’humanité : la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Le concept d’un corps capable de piéger la lumière, et donc de devenir invisible pour le reste de l’univers, avait été envisagé pour la première fois par les philosophes naturels John Michell et plus tard Pierre-Simon Laplace au 18e siècle. Ils ont calculé la vitesse de fuite d’une particule de lumière à partir d’un corps en utilisant les lois gravitationnelles de Newton, prédisant l’existence d’étoiles si denses que la lumière ne pourrait pas s’en échapper. Michell les a appelées “étoiles sombres”.

Mais après la découverte que la lumière se présentait sous la forme d’une onde en 1801, la manière dont la lumière serait affectée par le champ gravitationnel newtonien n’était plus claire et l’idée d’étoiles noires a été abandonnée. Il a fallu environ 115 ans pour comprendre comment la lumière sous forme d’onde se comporterait sous l’influence d’un champ gravitationnel, avec la découverte d’Albert Einstein .Théorie de la relativité générale en 1915, et celle de Karl Schwarzschild solution à ce problème un an plus tard.

Schwarzschild a également prédit l’existence d’une circonférence critique d’un corps, au-delà de laquelle la lumière serait incapable de passer : le rayon de Schwarzschild. Cette idée était similaire à celle de Michell, mais cette circonférence critique était maintenant comprise comme une barrière impénétrable.

Le rayon de Schwarzchild. Crédit : Tetra Quark/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Ce n’est qu’en 1933 que George Lemaître a montré que cette impénétrabilité n’était qu’une illusion qu’aurait un observateur distant. En utilisant la désormais célèbre illustration d’Alice et Bob, le physicien a émis l’hypothèse que si Bob restait immobile tandis qu’Alice sautait dans le black hole, Bob would see Alice’s image slowing down until freezing just before reaching the Schwarzschild radius. Lemaître also showed that in reality, Alice crosses that barrier: Bob and Alice just experience the event differently.

Despite this theory, at the time there was no known object of such a size, nothing even close to a black hole. As a result, no one believed that something resembling the dark stars as hypothesized by Michell would exist. In fact, no one even dared to treat the possibility with seriousness. Not until the Second World War.

From dark stars to black holes

On September 1, 1939, the Nazi German army invaded Poland, triggering the beginning of the war that changed the world’s history forever. Remarkably, it was on this very same day that the first academic paper on black holes was published. The now acclaimed article, On Continued Gravitational Contraction, by J Robert Oppenheimer and Hartland Snyder, two American physicists, was a crucial point in the history of black holes. This timing seems particularly odd when you consider the centrality of the rest of World War II in the development of the theory of black holes.

This was Oppenheimer’s third and final paper in astrophysics. In it, he and Snyder predict the continued contraction of a star under the influence of its own gravitational field, creating a body with an intense attraction force that not even light could escape from it. This was the first version of the modern concept of a black hole, an astronomical body so massive that it can only be detected by its gravitational attraction.

In 1939, this was still an idea that was too strange to be believed. It would take two decades until the concept was developed enough that physicists would start to accept the consequences of the continued contraction described by Oppenheimer. And World War II itself had a crucial role in its development, because of the US government’s investment in researching atomic bombs.

Einstein and Oppenheimer, around 1950. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Reborn from the ashes

Oppenheimer, of course, was not only an important character in the history of black holes. He would later become the head of the Manhattan Project, the research center that led to the development of atomic weapons.

Politicians understood the importance of investing in science in order to bring military advantage. Consequently, across the board, there was a wide investment in war-related revolutionary physics research, nuclear physics, and the development of new technologies. All sorts of physicists dedicated themselves to this kind of research, and as an immediate consequence, the fields of cosmology and astrophysics were mostly forgotten, including Oppenheimer’s paper.

In spite of the decade lost to large-scale astronomical research, the discipline of physics thrived as a whole as a result of the war – in fact, military physics ended up augmenting astronomy. The US left the war as the center of modern physics. The number of PhDs skyrocketed, and a new tradition of postdoctoral education was set up.

By the end of the war, the study of the universe was rekindled. There was a renaissance in the once underestimated theory of general relativity. The war changed the way we do physics: and eventually, this led to the fields of cosmology and general relativity getting the recognition they deserve. And this was fundamental to the acceptance and understanding of the black holes.

Princeton University then became the center of a new generation of relativists. It was there that the nuclear physicist, John A Wheeler, who later popularized the name “black hole,” had his first contact with general relativity, and reanalyzed Oppenheimer’s work. Skeptical at first, the influence of close relativists, new advances in computational simulation, and radio technology – developed during the war – turned him into the greatest enthusiast for Oppenheimer’s prediction on the day that war broke out, September 1, 1939.

Since then, new properties and types of black holes have been theorized and discovered, but all this only culminated in 2015. The measurement of the gravitational waves created in a black hole binary system was the first concrete proof that black holes exist.

Written by Carla Rodrigues Almeida, Visiting Postdoctoral Fellow, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.