Les avantages du vérapamil, un médicament contre l’hypertension artérielle, comprennent le retardement de la progression de la maladie, la diminution des besoins en insuline et la préservation de certaines fonctions des cellules bêta.

L’utilisation du médicament vérapamil pour traiter le diabète de type 1 continue de montrer des avantages qui durent au moins deux ans, rapportent des chercheurs dans le journal. Nature Communications. Les patients qui prennent ce médicament oral contre l’hypertension artérielle ont non seulement besoin de moins d’insuline quotidienne deux ans après le premier diagnostic de la maladie, mais ont également montré des preuves de bénéfices immunomodulateurs surprenants.

La poursuite du traitement était nécessaire. Dans l’étude de deux ans, les sujets qui ont cessé de prendre des doses quotidiennes de vérapamil à un an ont vu leur maladie s’aggraver à deux ans à des taux similaires à ceux du groupe témoin de patients diabétiques qui n’utilisaient pas du tout le vérapamil.

Le diabète de type 1 est une maladie auto-immune qui entraîne la perte des cellules bêta du pancréas, qui produisent l’insuline endogène. Pour remplacer l’insuline endogène, les patients doivent prendre de l’insuline exogène par injection ou par pompe et sont exposés à des risques d’hypoglycémie. Il n’existe actuellement aucun traitement oral pour cette maladie.

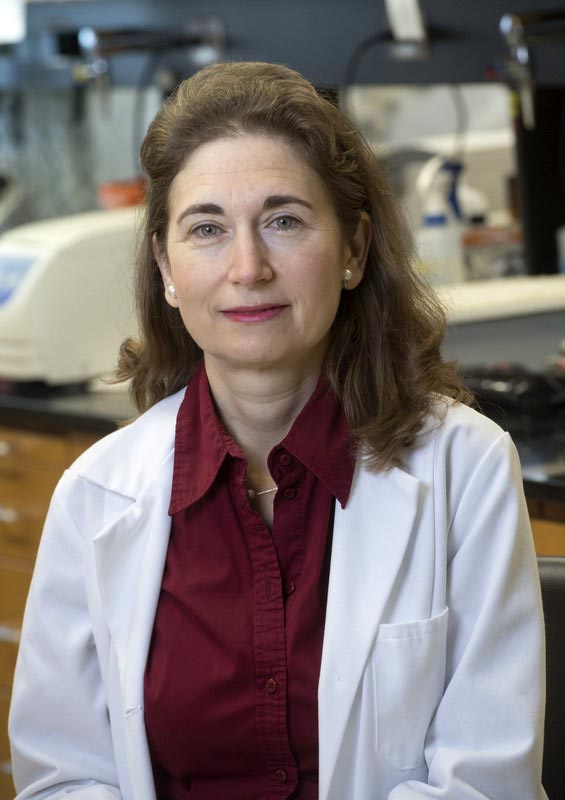

Anath Shalev. Crédit : UAB

La suggestion que le vérapamil pourrait servir de médicament potentiel contre le diabète de type 1 est une découverte fortuite du chef de l’étude, Anath Shalev, M.D., directeur du Comprehensive Diabetes Center de l’Université d’Alabama à Birmingham. Cette découverte est le fruit de plus de vingt ans de recherche fondamentale. recherche fondamentale sur un gène des îlots pancréatiques appelé TXNIP. En 2014, le laboratoire de recherche de Shalev, à l’UAB. a rapporté que le vérapamil inversait complètement le diabète dans des modèles animaux, et elle a annoncé son intention de tester les effets du médicament dans un essai clinique sur l’homme. La Food and Drug Administration des États-Unis a approuvé le vérapamil pour le traitement de l’hypertension artérielle en 1981.

En 2018, Shalev et ses collègues ont rapporté les avantages du vérapamil dans une étude clinique d’un an sur des patients atteints de diabète de type 1, constatant que l’administration orale régulière de vérapamil permettait aux patients de produire des niveaux plus élevés de leur propre insuline, limitant ainsi leur besoin d’insuline injectée pour réguler la glycémie.

L’étude actuelle prolonge cette découverte et fournit des informations mécanistes et cliniques cruciales sur les effets bénéfiques du vérapamil dans le diabète de type 1, en utilisant l’analyse protéomique et RNA sequencing.

To examine changes in circulating proteins in response to verapamil treatment, the researchers used liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry of blood serum samples from subjects diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes within three months of diagnosis and at one year of follow-up. Fifty-three proteins showed significantly altered relative abundance over time in response to verapamil. These included proteins known to be involved in immune modulation and autoimmunity of Type 1 diabetes.

The top serum protein altered by verapamil treatment was chromogranin A, or CHGA, which was downregulated with treatment. CHGA is localized in secretory granules, including those of pancreatic beta cells, suggesting that changed CHGA levels might reflect alterations in beta cell integrity. In contrast, the elevated levels of CHGA at Type 1 diabetes onset did not change in control subjects who did not take verapamil.

CHGA levels were also easily measured directly in serum using a simple ELISA assay after a blood draw, and lower levels in verapamil-treated subjects correlated with better endogenous insulin production as measured by mixed-meal-stimulated C-peptide, a standard test of Type 1 diabetes progression. Also, serum CHGA levels in healthy, non-diabetic volunteers were about twofold lower compared to subjects with Type 1 diabetes, and after one year of verapamil treatment, verapamil-treated Type 1 diabetes subjects had similar CHGA levels compared with healthy individuals. In the second year, CHGA levels continued to drop in verapamil-treated subjects, but they rose in Type 1 diabetes subjects who discontinued verapamil during year two.

“Thus, serum CHGA seems to reflect changes in beta cell function in response to verapamil treatment or Type 1 diabetes progression and therefore may provide a longitudinal marker of treatment success or disease worsening,” Shalev said. “This would address a critical need, as the lack of a simple longitudinal marker has been a major challenge in the Type 1 diabetes field.”

Other labs have identified CHGA as an autoantigen in Type 1 diabetes that provokes immune T cells involved in the autoimmune disease. Thus, Shalev and colleagues asked whether verapamil affected T cells. They found that several proinflammatory markers of T follicular helper cells, including CXCR5 and interleukin 21, were significantly elevated in monocytes from subjects with Type 1 diabetes, as compared to healthy controls, and they found that these changes were reversed by verapamil treatment.

“Now our results reveal for the first time that verapamil treatment may also affect the immune system and reverse these Type 1 diabetes-induced changes,” Shalev said. “This suggests that verapamil, and/or the Type 1 diabetes improvements achieved by it, can modulate some circulating proinflammatory cytokines and T helper cell subsets, which in turn may contribute to the overall beneficial effects observed clinically.”

To assess changes in gene expression, RNA sequencing of human pancreatic islet samples exposed to glucose, with or without verapamil was performed and revealed a large number of genes that were either upregulated or downregulated. Analysis of these genes showed that verapamil regulates the thioredoxin system, including TXNIP, and promotes an anti-oxidative, anti-apoptotic and immunomodulatory gene expression profile in human islets. Such protective changes in the pancreatic islets might further explain the sustained improvements in pancreatic beta cell function observed with continuous verapamil use.

Shalev and colleagues caution that their study, with its small number of subjects, needs to be confirmed by larger clinical studies, such as a current verapamil-Type 1 diabetes study ongoing in Europe.

But the preservation of some beta cell function is promising. “In humans with Type 1 diabetes, even a small amount of preserved endogenous insulin production — as opposed to higher exogenous insulin requirements — has been shown to be associated with improved outcomes and could help improve quality of life and lower the high costs associated with insulin use,” Shalev said. “The fact that these beneficial verapamil effects seemed to persist for two years, whereas discontinuation of verapamil led to disease progression, provides some additional support for its potential usefulness for long-term treatment.”

Reference: “Exploratory study reveals far reaching systemic and cellular effects of verapamil treatment in subjects with type 1 diabetes” by 3 March 2022, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-28826-3

At UAB, Shalev is a professor in the Department of Medicine Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, and she holds the Nancy R. and Eugene C. Gwaltney Family Endowed Chair in Juvenile Diabetes Research.

Co-authors with Shalev, in the Nature Communications report “Exploratory study reveals far reaching systemic and cellular effects of verapamil treatment in subjects with type 1 diabetes,” are Guanlan Xu, Tiffany D. Grimes, Truman B. Grayson, Junqin Chen, Lance A. Thielen and Fernando Ovalle, UAB Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism; Hubert M. Tse, UAB Department of Microbiology; Peng Li, UAB School of Nursing; Matt Kanke and Praveen Sethupathy, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York; and Tai-Tu Lin, Athena A. Schepmoes, Adam C. Swensen, Vladislav A. Petyuk and Wei-Jun Qian, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington.

Support came from National Institutes of Health grants DK078752, Human Islet Research Network DK120379, DK110844 and DK122160; and the American Diabetes Association Pathway Award 1-16-ACE-47.

The UAB departments of Medicine and Microbiology and the UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center are part of the Marnix E. Heersink School of Medicine.