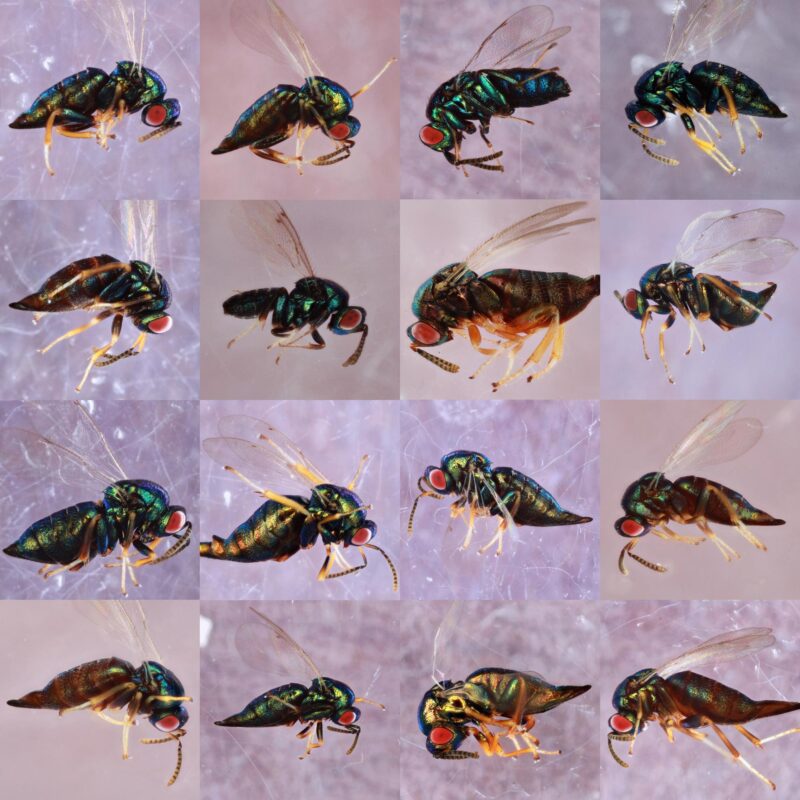

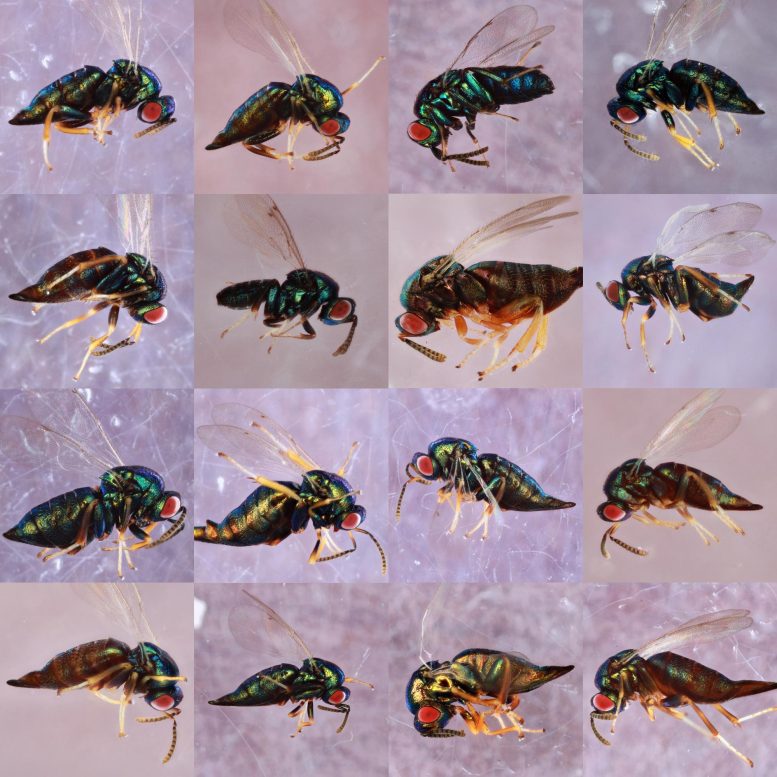

Certaines espèces non découvertes se cachent juste sous notre nez. Ormyrus labotus, une minuscule guêpe parasitoïde connue de la science depuis 1843, a longtemps été considérée comme une généraliste, pondant ses œufs sur plus de 65 espèces différentes d’autres insectes. Mais une nouvelle étude parue dans Insect Systematics and Diversity suggère que les guêpes actuellement appelées Ormyrus labotus sont en fait au moins 16 espèces différentes, identiques en apparence mais génétiquement distinctes, chacune parasitant une gamme plus étroite d’espèces hôtes. On voit ici des spécimens de guêpes collectés par des chercheurs de l’Université de l’Iowa qui correspondent tous à la description d’Ormyrus labotus. Mais, en combinant l’analyse génétique avec des données sur les attributs physiques et les facteurs écologiques des guêpes, les chercheurs affirment que ces guêpes appartiennent toutes à des espèces distinctes – une découverte qui souligne l’importance de rechercher la “diversité cachée” du monde. Crédit : image de la galerie par Entomological Society of America ; images des composants par Sofia Sheikh, Anna Ward et Andrew Forbes, Université de l’Iowa.

Des techniques génétiques avancées révèlent l’existence de plusieurs guêpes parasitoïdes semblables, auparavant regroupées en une seule espèce.

Un refrain courant chez les biologistes veut que la majorité des espèces végétales et animales de la Terre n’aient pas encore été découvertes. Si beaucoup de ces espèces vivent dans des zones étroites ou difficiles d’accès, d’autres peuvent en fait se cacher juste sous notre nez.

Prenez Ormyrus labotusOrmyrus labotus, une minuscule guêpe parasitoïde connue de la science depuis 1843. Elle a longtemps été considérée comme un généraliste, pondant ses œufs sur plus de 65 espèces différentes d’autres insectes. Mais une nouvelle étude publiée aujourd’hui dans Insect Systematics and Diversity suggère que les guêpes actuellement appelées Ormyrus labotus sont en fait au moins 16 espèces différentes, identiques en apparence mais génétiquement distinctes.

Il n’est pas rare, surtout avec les progrès des techniques génétiques, de découvrir des espèces “cryptiques” au sein d’une espèce d’insecte connue, mais le nombre de celles qui ont été trouvées au sein de l’espèce n’est pas négligeable.Ormyrus labotus souligne l’importance de rechercher la “diversité cachée” du monde, déclare Andrew Forbes, Ph, professeur agrégé de biologie à l’Université de l’Iowa. University of Iowa and senior author of the study.

“We know so much from ecology about how important even the smallest species can be to an ecosystem,” he says, “such that uncovering this hidden diversity—and, maybe more importantly, understanding the biology of each species—becomes a critical component of conservation and maintenance of ecosystem health.”

Intriguing Insects That Emerge From Oak Galls

Parasitoid wasps lay their eggs on or in other insects and arthropods, and they commonly specialize in parasitizing a small number of host species, or even just one. Meanwhile, a wide variety of insects lay their eggs on plants where their larvae hatch and then induce the plant to form a protective structure called a “gall” around the larvae. Wasps in the genus Ormyrus parasitize these gall-forming insects.

For a separate research project between 2015 and 2019, Sofia Sheikh and Anna Ward, both graduate students in Forbes’ lab, collected galls formed on oak trees and observed the insects that emerged. They noticed that wasps emerging from a large diversity of gall types all matched the description of Ormyrus labotus, and this got the researchers wondering.

“It seemed highly unusual for one parasitoid species to be able to exploit such a wide and dynamic set of hosts,” says Sheikh, a master’s student at the time in Forbes’ lab (now a Ph.D. student at the University of Chicago) and lead author on the new study.

To test whether the wasps they collected were all truly one species or instead a band of look-alikes, Sheikh, Ward, and Forbes extracted DNA samples from each of the wasp specimens that emerged from the oak galls and analyzed the degree of genetic variation between them, with assistance from collaborators at Rice University and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Then they combined this genetic analysis with data on the wasps’ physical attributes and ecological factors—e.g., which type of oak galls they emerged from, at what time of year, and so on—to place the wasps in groups of likely separate species.

The final result? The collected wasps that originally appeared to be Ormyrus labotus instead comprise at least 16 distinct species, and possibly as many as 18.

The Hunt for Cryptic Species

In their review of other research, the team found several other studies that had uncovered cryptic species within purported generalist species but none that had found so many at once. And it’s possible more distinct species that would otherwise match O. labotus remain to be found, the researchers say, because the original collection of oak-gall specimens that Sheikh and Ward conducted wasn’t designed to encompass all known O. labotus hosts.

For now, Ormyrus labotus will remain a “species complex,” with these newly delineated species known to exist but not yet formally described and named. Forbes says his lab “only dabbles” in formal taxonomy, but all specimens from the study have been preserved and are available for other researchers who want to conduct a taxonomic revision of the Ormyrus genus. “If someone wants to take a crack at naming these species of Ormyrus, we’re ready to help however we can,” he says.

Until then, the current findings underscore the importance of fundamental biodiversity research and its potential implications. For example, if O. labotus were ever enlisted for control of an invasive oak-galling pest, it would be critical to know which species within the complex targeted that specific pest species—and the same dynamic applies in the use of any parasitoid wasp species for biological control. Meanwhile, failing to differentiate specialists from generalists hinders scientists’ ability to understand actual generalist insects and what enables them to target a variety of hosts, the researchers note.

Sheikh says she sees parasitoid wasps as “emblems of weird—i.e., interesting—biology” and is intrigued by their specialization strategies. “More so than any specific number of potential new species, I am excited about how this study and many others are revealing a plethora of cryptic diversity,” she says. “This, to me, suggests that we still have a lot to learn about the processes that structure species interactions with each other and their environments.”

Reference: “Ormyrus labotus Walker (Hymenoptera: Ormyridae): another generalist that should not be a generalist is not a generalist” by Sofia I Sheikh, Anna K G Ward, Y Miles Zhang, Charles K Davis, Linyi Zhang, Scott P Egan and Andrew A Forbes, 16 February 2022, Insect Systematics and Diversity.

DOI: 10.1093/isd/ixac001