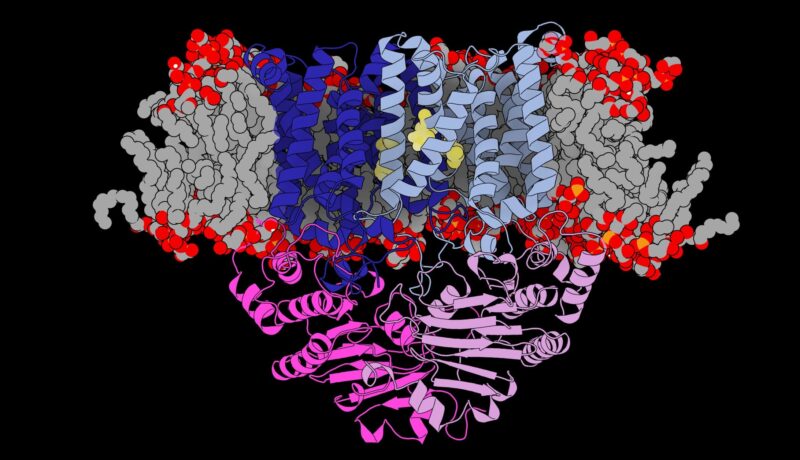

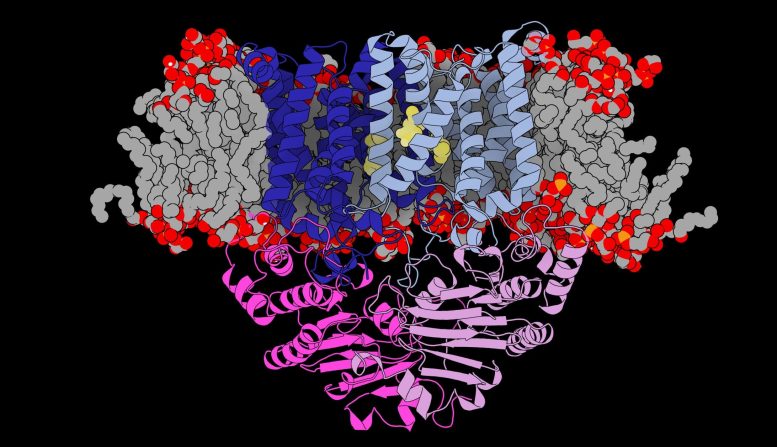

Les chercheurs ont déterminé la structure de la “porte” unique que le pneumocoque utilise pour voler le manganèse de l’organisme. Crédit : Université de Melbourne

Des chercheurs australiens ont révélé comment la bactérie Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumocoque) obtient le nutriment essentiel, le manganèse, de notre corps, ce qui pourrait conduire à de meilleures thérapies pour cibler ce pathogène résistant aux antibiotiques et potentiellement mortel.

Le pneumocoque est l’un des organismes les plus mortels au monde, responsable de plus d’un million de décès chaque année, et constitue la première cause infectieuse de mortalité chez les enfants de moins de cinq ans. C’est la principale cause de pneumonie bactérienne, ainsi qu’une cause majeure de méningite, de septicémie et d’infections de l’oreille interne (otite moyenne).

Publié en Science Advances et après dix ans d’investigations détaillées, les chercheurs du Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity – une joint-venture entre l’Université de Melbourne et le Royal Melbourne Hospital – et le Bio21 Molecular Science & ; Biotechnology Institute (Bio21), ainsi que des collaborateurs du Australian National University and Kyoto University, Japan, have determined the structure of the unique ‘gateway’ that pneumococcus uses to steal manganese from the body.

All organisms, including pathogens, need vitamins and minerals to survive. While researchers knew that manganese was critical for survival of the pneumococcus, how it took manganese from the body wasn’t understood.

University of Melbourne Associate Professor Megan Maher, a laboratory head at Bio21, said they noticed the bacterium was drawing in nutrients in a regulated way.

“Eventually we discovered that this was due to a unique gateway that sits in the bacterium’s membrane that opens and closes to specifically allow manganese in,” said Associate Professor Maher.

“This is a completely new structure that has never been seen in a pathogen like this.”

University of Melbourne Professor Christopher McDevitt, a laboratory head at the Doherty Institute, said the study’s finding changes what we know about the pathogen’s survival.

“Previously, it was thought that these gateways acted like Teflon coated channels in the sense that everything just flowed through,” explained Professor McDevitt.

“Now we understand that it is selectively drawing the manganese in. Any disturbance of this gateway starves the pathogen of manganese, which prevents it from being able to cause disease.”

It could hold the key to better and alternative therapies against the pneumococcus.

Although a pneumococcal vaccine does exist, it only provides limited protection against circulating strains, and antibiotic resistance rates are rapidly rising.

“It’s a really attractive therapeutic target as it sits on the surface of the bacterium, and our bodies don’t use this type of gateway,” Professor McDevitt said

“At a time when we are seeing rising resistance to our first and last line antibiotics, and the emergence of ‘superbugs’, it is important that we think of new strategies to control this deadly organism.”

Reference: “The structural basis of bacterial manganese import” by Stephanie L. Neville, Jennie Sjöhamn, Jacinta A. Watts, Hugo MacDermott-Opeskin, Stephen J. Fairweather, Katherine Ganio, Alex Carey Hulyer, Aaron P. McGrath, Andrew J. Hayes, Tess R. Malcolm, Mark R. Davies, Norimichi Nomura, So Iwata, Megan L. O’Mara, Megan J. Maher and Christopher A. McDevitt, 6 August 2021, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abg3980