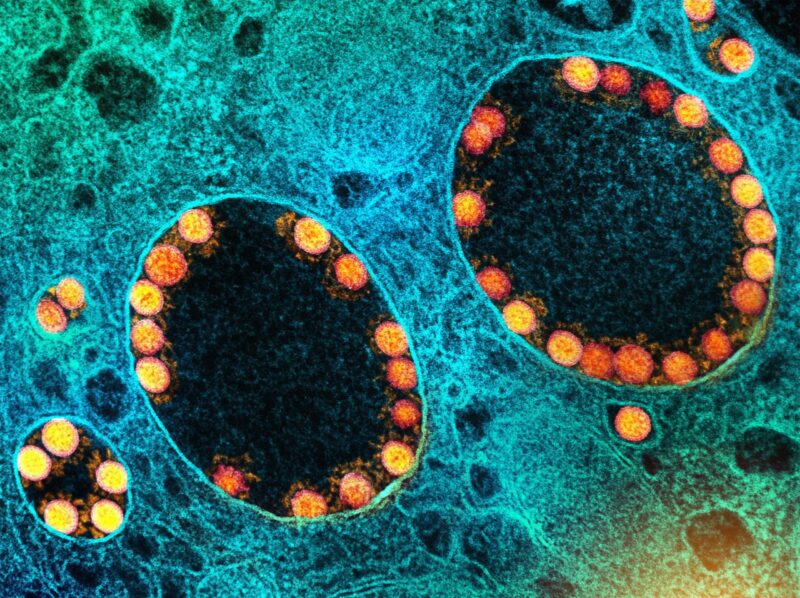

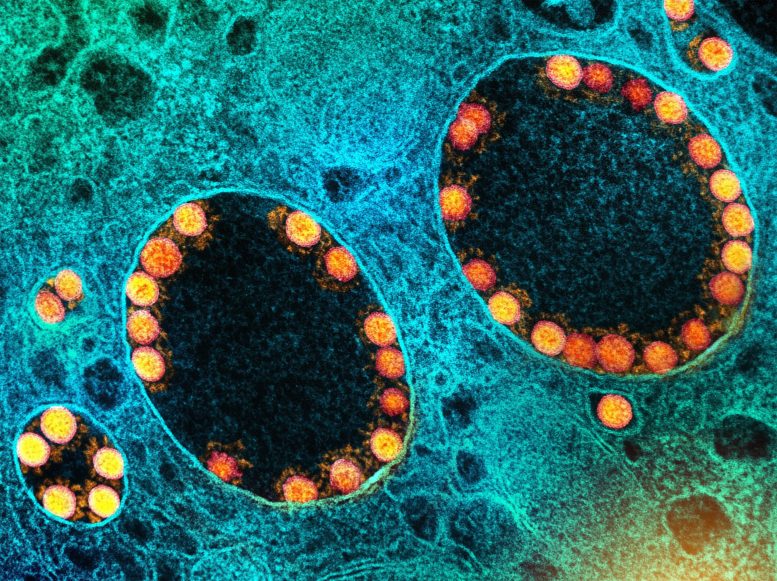

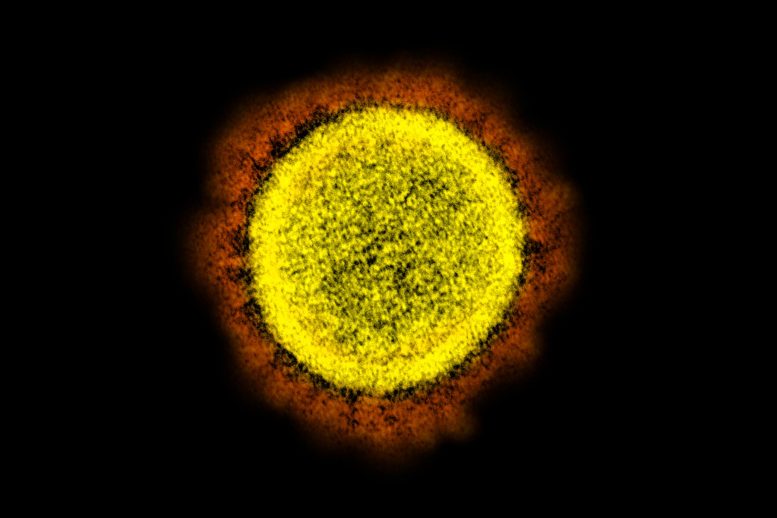

De nouvelles variantes du SRAS-CoV-2, le virus responsable du COVID-19, apparaissent par le biais de mutations lorsque le virus se réplique dans les cellules d’un hôte infecté. Crédit : NIAID

La nature est analogique. Ce n’est pas un système binaire. Dans le monde vivant, il n’existe pas d’interrupteurs explicites qui activent ou désactivent discrètement les systèmes. Au contraire, la nature ajuste les systèmes par le biais de cadrans analogiques, comme une vieille radio – en changeant progressivement les variables pour atteindre l’équilibre, afin de garantir la pérennité de la vie et sa continuité.

L’évolution se déroule de cette manière, de nouvelles formes de vie apparaissant et d’autres disparaissant au cours des millénaires – ou, dans le cas des pathogènes microbiens (virus, bactéries et parasites) en quelques jours ou semaines.

Le changement évolutif résulte de deux forces opposées: La sélection positive reproduit les variations génétiques bénéfiques qui permettent au virus de survivre, tandis que la pression de sélection négative entrave la survie du virus et sa capacité à se reproduire.

L’évolution peut être étudiée au niveau moléculaire. Pour nombreuses années, mes recherches était axée sur le Trypanosome africain, le parasite responsable de la maladie du sommeil en Afrique.

Variation antigénique

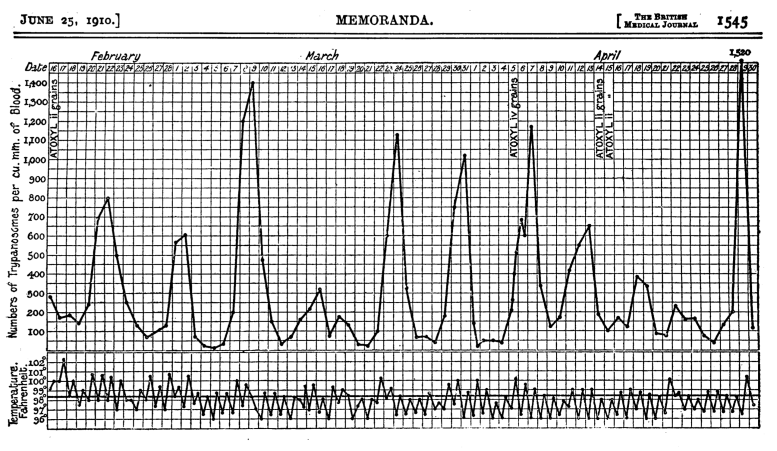

Les trypanosomes vivent dans la circulation sanguine de leurs hôtes mammifères (y compris l’homme) et les premières observations de leur nombre ont montré un modèle cohérent en forme de vague d’augmentations suivies de diminutions puis, après une semaine environ, d’une nouvelle augmentation.

Courbe de croissance de la trypanosomiase africaine chez un humain infecté. Ross, R., & ; Thomson, D. (1910). Un cas de maladie du sommeil montrant l’augmentation périodique régulière des parasites divulgués. Crédit : Br Med J, 1(2582), 1544-1545. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.2, CC BY-NC

Les trypanosomes sont vulnérables aux anticorps produits par le système immunitaire de leur hôte, qui se lient au parasite et l’éliminent. Cette réponse immunitaire fait chuter le nombre de trypanosomes, comme l’illustrent les points bas de la vague. Mais avant que les trypanosomes ne disparaissent complètement, leur nombre augmente à nouveau et la vague se répète.

Ce schéma de croissance intriguant a suscité beaucoup d’intérêt et de recherches dans mon laboratoire et, finalement, nous avons appris que le parasite peut modifier son identité moléculaire pour échapper aux anticorps de l’hôte avant d’être complètement éliminé. Cela signifie que la population de trypanosomes responsable de chacun des pics de la vague est une variante distincte de toutes les autres. Les anticorps dirigés contre une variante n’ont aucun effet sur les variantes suivantes.Le modèle de vague continue donc.

La stratégie très réussie du trypanosome a évolué pour l’aider à survivre face à la pression de sélection négative constante des anticorps.. Ce mécanisme qui aide un parasite ou un agent pathogène à échapper au système immunitaire de l’hôte est appelé variation antigénique.

Les vagues de COVID-19 sont similaires à la maladie du sommeil.

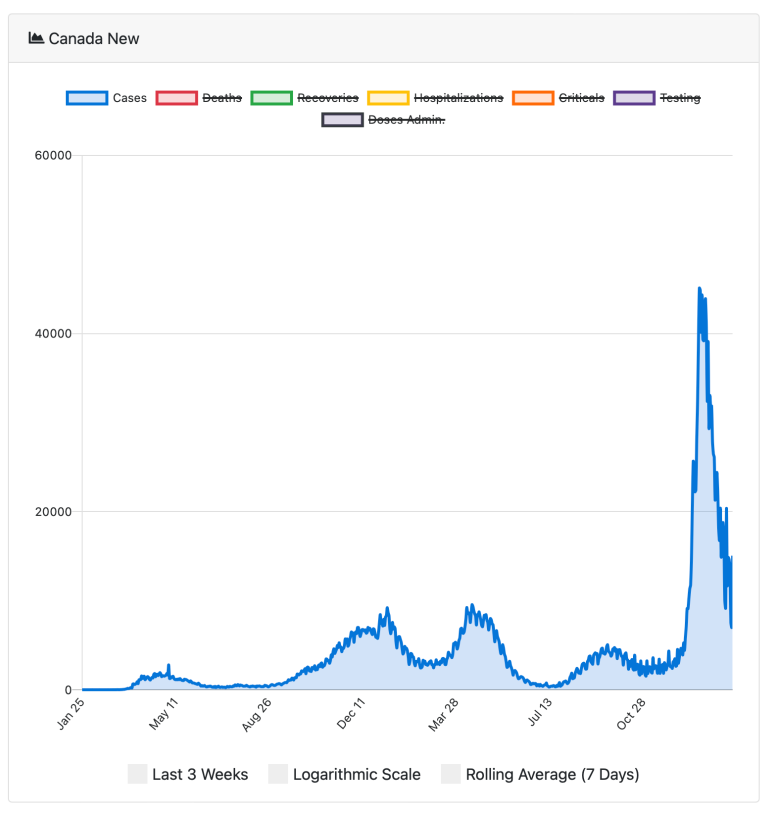

La courbe de croissance des trypanosomes me revient à l’esprit lorsque je regarde le modèle de dénombrement des cas canadiens de l’enquête en cours sur le COVID-19 pandemic.

Case counts of COVID-19 in Canada since January 25, 2020. Credit: N. Little. COVID-19 Tracker Canada (2020)

The peaks in cases reflect the arrival of new variants, the most recent of which is omicron, the variant now circulating most widely globally.

The strategy used by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is similar to the trypanosome’s, although the mechanism for generating novel variants is quite different. For the virus, new variants arise by mutation in genes that encode the so-called “spike protein,” the part of the virus that enables it to enter cells and infect people.

Mutations arise due to “errors” that occur when the virus is replicating itself in the cells of the host’s respiratory system. Because the virus has a mechanism that can attempt to repair the “errors,” SARS-CoV-2 evolves more slowly than the trypanosome. It evolves more slowly because the virus has a mechanism that can try to repair the “errors.” However, this repair process is not perfect, and some mutations get retained.

If mutations result in a spike protein distinct from any other variant preceding it, we will see a new variant appearing. The omicron variant is particularly interesting (and somewhat ominous) because of its high number of mutations, not only in the spike protein but in other viral genes as well.

The red projections seen on the outside of the SARS-CoV-2 virus are spike proteins, which enable the virus to attach to and infect host cells, and then replicate. Credit: NIAID

By employing this strategy of antigenic variation, the survival of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is assured. So, the appearance of new variants is due to mutations that represent the positive selection force: genetic variations that help the organism get reproduced.

The decline of case numbers during a pandemic is due to negative selection forces. These include effective public health interventions that limit the spread from one person to the next (such as masks), as well as the hosts’ immune response (antibodies) resulting from either infection, vaccination or both.

An infected person will, over time, generate antibodies against the virus and begin to eliminate that variant, like in the trypanosome case. But because SARS-CoV-2 mutations occur slowly, the virus needs to find a new, non-immune person to carry on. In order to find new non-immune hosts, the virus induces symptoms that help it to spread: the coughing and sneezing that enable it to jump from one person to the next via droplets.

Antibodies and illness

Given the capacity of SARS-CoV-2 to mutate, there are certainly new variants arising continuously. However, if medical and public health interventions are successful in reducing transmission between infected and uninfected/unvaccinated people, it is quite possible that the virus will evolve to generate a less virulent variant that could establish itself as an endemic infection producing mild symptoms.

When people infected with a pathogenic microbe experience symptoms of illness, those symptoms often serve a purpose: they can contribute to either the microbe’s survival or the survival of the infected host. A classic case is diarrhea resulting from infection with cholera or from amoebic dysentery. Both infections produce life-threatening diarrhea, but the symptom serves different purposes in each disease.

Transmission electron micrograph of alpha variant SARS-CoV-2 virus particles. Credit: NIAID

In the case of cholera, this symptom serves the microbe because it enables the bacteria to exit the host’s body and, in places with poor sanitation, contaminate the water supply and transmit to new hosts. In the case of amoebic dysentery, the symptom is a result of the host’s body attempting to rid itself of the infection.

Clinicians must be able to distinguish between these two scenarios in the management of infectious diseases in order to avoid contributing to the problem rather than solving it. In the case of COVID-19, clinical symptoms like sneezing and coughing that enable the virus to spread through the air are positively selecting variants that help the virus spread to new, susceptible individuals (such as unvaccinated people).

That means measures like masking, social distancing, and vaccination can impede spread by helping to prevent aerosol transmission.

Continued efforts to achieve a fully vaccinated population are crucial. The unvaccinated and the uninfected are ideal hosts for SARS-CoV-2, and ideal for generating new variants due to the absence of negative selection by antibodies, which makes it easier for the virus to replicate and produce new mutations.

Although nature may move slowly in an analog manner, humans can flip binary switches and we can act now to ensure global vaccine equity. Ensuring global vaccine coverage is not only imperative from an evolutionary perspective but is clearly the ethical option as well.

Written by Michael Clarke, Adjunct Professor, Interfaculty Program in Public Health, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University.