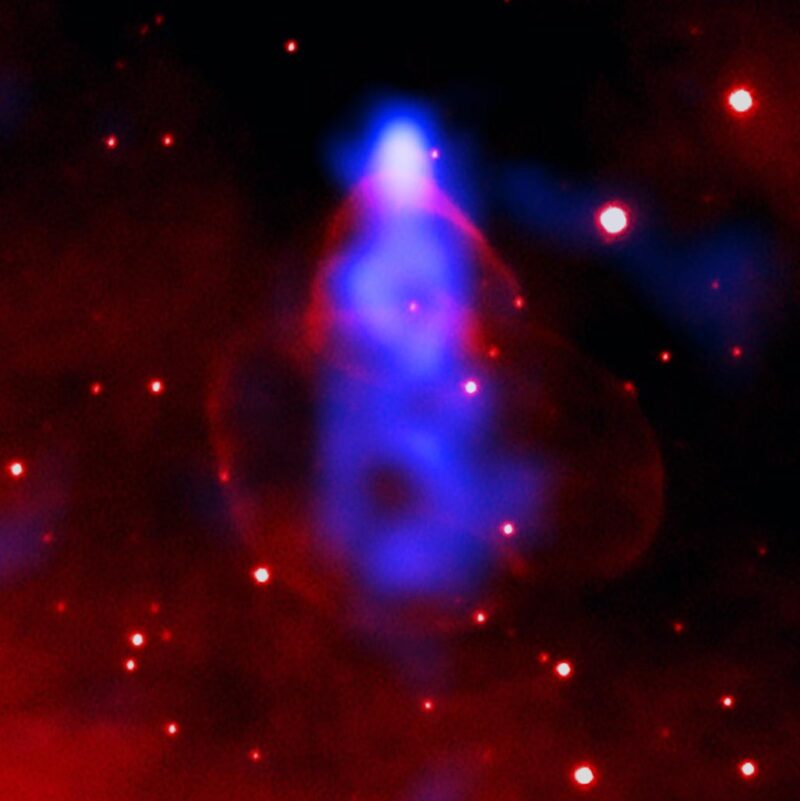

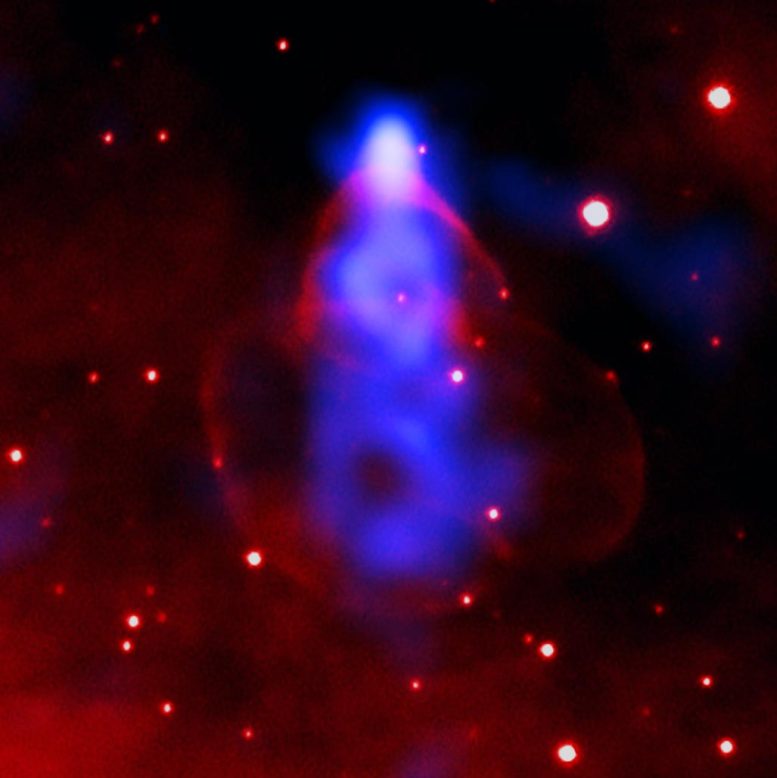

J2030 X-Ray et Optique. Crédit : Rayon X : NASA/CXC/Stanford Univ./M. de Vries ; Optique : NSF/AURA/Gemini Consortium.

- Une étoile effondrée de la taille d’une ville a généré un faisceau de matière et d’antimatière qui s’étend sur des trillions de kilomètres.

- Données de ;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory revealed the full extent of this beam, or filament.

- This discovery could help explain the presence of positrons detected throughout the Milky Way galaxy and here on Earth.

- Positrons are the antimatter counterpart to the electron.

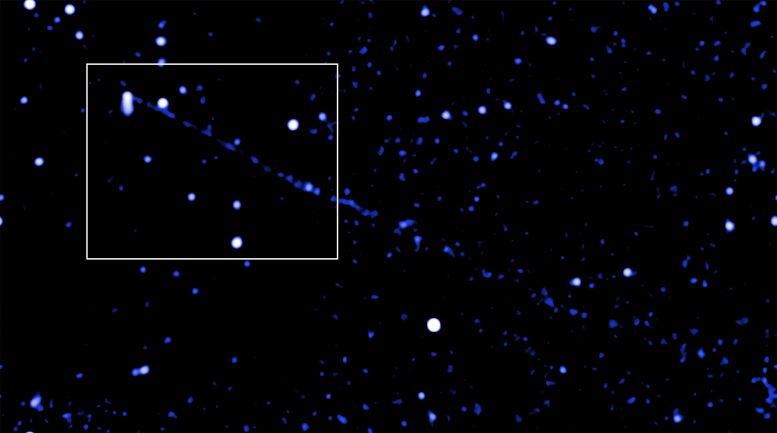

Cette image provenant de l’observatoire Chandra X de la NASA et de télescopes optiques terrestres montre un faisceau extrêmement long, ou filament, de matière et d’antimatière s’étendant depuis un pulsar. With its tremendous scale, this beam may help explain the surprisingly large numbers of positrons, the antimatter counterparts to electrons, scientists have detected throughout the Milky Way galaxy.

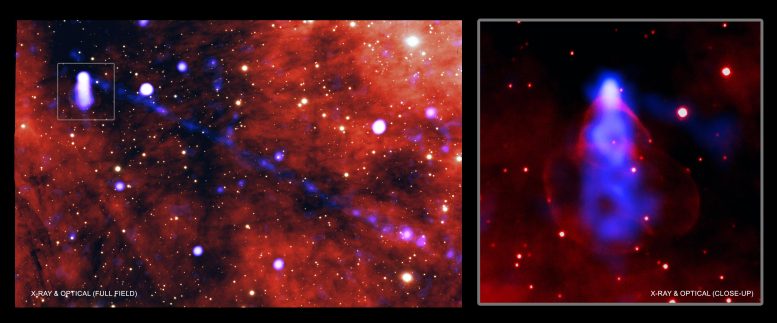

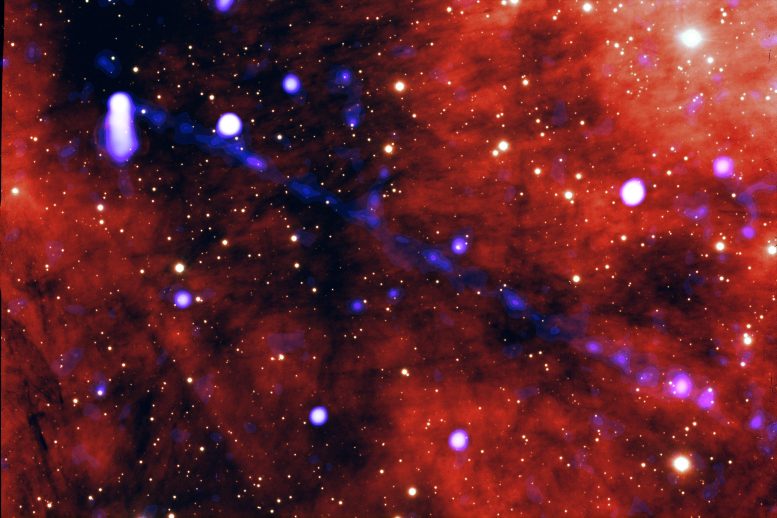

In the image at the top of the page, the panel on the left displays about one third the length of the beam from the pulsar known as PSR J2030+4415 (J2030 for short), which is located about 1,600 light years from Earth. J2030 is a dense, city-sized object that formed from the collapse of a massive star and currently spins about three times per second. X-rays from Chandra (blue) show where particles flowing from the pulsar along magnetic field lines are moving at about a third the speed of light. A close-up view of the pulsar in the right panel shows the X-rays created by particles flying around the pulsar itself. As the pulsar moves through space at about a million miles an hour, some of these particles escape and create the long filament. In both panels, optical light data from the Gemini telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii have been used and appear red, brown, and black. The full length of the filament is shown in a separate image (below).

J2030 X-Ray and Optical wide fieldCredit: NASA/CXC/Stanford Univ./M. de Vries

The vast majority of the Universe consists of ordinary matter rather than antimatter. Scientists, however, continue to find evidence for relatively large numbers of positrons in detectors on Earth, which leads to the question: what are possible sources of this antimatter? The researchers in the new Chandra study of J2030 think that pulsars like it may be one answer. The combination of two extremes — fast rotation and high magnetic fields of pulsars — lead to particle acceleration and high energy radiation that creates electron and positron pairs. (The usual process of converting mass into energy famously determined by Einstein’s E = mc2 equation is reversed, and energy is converted into mass.)

J2030 X-Ray full field. Credit: NASA/CXC/Stanford Univ./M. de Vries

Pulsars generate winds of charged particles that are usually confined within their powerful magnetic fields. The pulsar is traveling through interstellar space at about half a million miles per hour, with the wind trailing behind it. A bow shock of gas moves along in front of the pulsar, similar to the pile-up of water in front of a moving boat. However, about 20 to 30 years ago the bow shock’s motion appears to have stalled and the pulsar caught up to it.

J2030 X-Ray and Optical close-up. Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Stanford Univ./M. de Vries; Optical: NSF/AURA/Gemini Consortium

The ensuing collision likely triggered a particle leak, where the pulsar wind’s magnetic field linked up with the interstellar magnetic field. As a result, the high-energy electrons and positrons could have squirted out through a “nozzle” formed by connection into the Galaxy.

Auparavant, les astronomes ont observé de grands halos autour des pulsars proches dans la lumière gamma, ce qui implique que les positrons énergétiques ont généralement du mal à s’échapper dans la Galaxie. Cette constatation affaiblit l’idée que les pulsars expliquent l’excès de positrons que les scientifiques détectent. Cependant, les filaments de pulsars qui ont été récemment découverts, comme J2030, montrent que les particules peuvent effectivement s’échapper dans l’espace interstellaire, et pourraient éventuellement atteindre la Terre.

Pour en savoir plus sur cette découverte, voir Tiny Star Unleashes Gargantuan Beam of Matter and Anti-Matter That Stretches for 40 Trillion Miles.

Référence : “Le long filament de PSR J2030+4415” par Martijn de Vries et Roger W. Romani, Accepté, The Astrophysical Journal.

arXiv:2202.03506

Un article décrivant ces résultats, rédigé par Martjin de Vries et Roger Romani de l’université de Stanford, paraîtra dans The Astrophysical Journal. Le Marshall Space Flight Center de la NASA gère le programme Chandra. Le Chandra X-ray Center du Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory contrôle les opérations scientifiques depuis Cambridge, Massachusetts, et les opérations de vol depuis Burlington, Massachusetts.