Des chercheurs se préparent à lancer un équipement d’échantillonnage à Port Hacking, dans l’est de l’Australie. Crédit : Université de technologie de Sydney

Un prédateur océanique microscopique qui a le goût de la capture du carbone

Un microbe marin unicellulaire capable de faire de la photosynthèse et de chasser et manger des proies pourrait être une arme secrète dans la lutte contre le changement climatique.

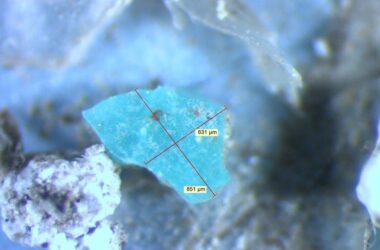

Des scientifiques de l’Université de Technologie de Sydney (UTS) ont découvert une nouvelle espèce qui a le potentiel de séquestrer naturellement le carbone, même si les océans se réchauffent et deviennent plus acides.

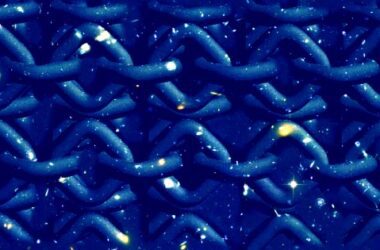

Ce microbe, abondant dans le monde entier, réalise la photosynthèse et libère un exopolymère riche en carbone qui attire et immobilise d’autres microbes. Il mange ensuite une partie des proies piégées avant d’abandonner sa “mucosphère” d’exopolymère. Ayant piégé d’autres microbes, l’exopolymère devient plus lourd et coule, faisant partie de la pompe à carbone biologique naturelle de l’océan.

Le Dr Michaela Larsson, biologiste marin, a dirigé la recherche, publiée dans la revue “The Journal”. Nature CommunicationsElle affirme que cette étude est la première à démontrer ce comportement.

Les microbes marins régissent la biogéochimie océanique par le biais d’une série de processus, notamment l’exportation verticale et la séquestration du carbone, qui modulent finalement le climat mondial.

Selon Mme Larsson, si la contribution du phytoplancton à la pompe à carbone est bien établie, le rôle des autres microbes est beaucoup moins connu et rarement quantifié. Elle précise que cela est particulièrement vrai pour les protistes mixotrophes, qui peuvent à la fois faire de la photosynthèse et consommer d’autres organismes.

“La plupart des plantes terrestres utilisent les nutriments du sol pour se développer, mais certaines, comme la Venus flytrap, gain additional nutrients by catching and consuming insects. Similarly, marine microbes that photosynthesize, known as phytoplankton, use nutrients dissolved in the surrounding seawater to grow,” Dr. Larsson says.

“However, our study organism, Prorocentrum cf. balticum, is a mixotroph, so is also able to eat other microbes for a concentrated hit of nutrients, like taking a multivitamin. Having the capacity to acquire nutrients in different ways means this microbe can occupy parts of the ocean devoid of dissolved nutrients and therefore unsuitable for most phytoplankton.”

Professor Martina Doblin, senior author of the study, says the findings have global significance for how we see the ocean balancing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The researchers estimate that this species, isolated from waters offshore from Sydney, has the potential to sink 0.02-0.15 gigatons of carbon annually. A 2019 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report found that to meet climate goals, CO2 removal technologies and strategies will need to remove approximately 10 gigatons of CO2 from the atmosphere every year until 2050.

“This is an entirely new species, never before described in this amount of detail. The implication is that there’s potentially more carbon sinking in the ocean than we currently think, and that there is perhaps greater potential for the ocean to capture more carbon naturally through this process, in places that weren’t thought to be potential carbon sequestration locations,” Professor Doblin says.

She says an intriguing question is whether this process could form part of a nature-based solution to enhance carbon capture in the ocean.

“The natural production of extra-cellular carbon-rich polymers by ocean microbes under nutrient-deficient conditions, which we’ll see under global warming, suggest these microbes could help maintain the biological carbon pump in the future ocean.”

“The next step before assessing the feasibility of large-scale cultivation is to gauge the proportion of the carbon-rich exopolymers resistant to bacteria breakdown and determine the sinking velocity of discarded mucospheres.

“This could be a game changer in the way we think about carbon and the way it moves in the marine environment.”

Reference: “Mucospheres produced by a mixotrophic protist impact ocean carbon cycling” 14 March 2022, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-28867-8