MediSCAPE, un microscope 3D à haute vitesse conçu par les ingénieurs de Columbia, peut voir en temps réel les détails cellulaires des tissus vivants pour guider la chirurgie, accélérer les analyses de tissus et améliorer les traitements.

Une équipe d’ingénieurs de Columbia a mis au point une technologie qui pourrait remplacer les biopsies et l’histologie conventionnelles par une imagerie en temps réel dans le corps vivant. Cette technologie est décrite dans un nouvel article publié aujourd’hui (28 mars 2022) dans la revue .Nature Biomedical EngineeringMediSCAPE est un microscope 3D à haute vitesse capable de capturer des images de structures tissulaires qui pourraient guider les chirurgiens dans le repérage des tumeurs et de leurs limites sans qu’il soit nécessaire de retirer les tissus et d’attendre les résultats de l’examen pathologique.

Pour de nombreuses procédures médicales, notamment la chirurgie et le dépistage du cancer, il est courant que les médecins effectuent une biopsie, c’est-à-dire qu’ils prélèvent de petits morceaux de tissus pour pouvoir les examiner de plus près au microscope. “La façon dont les échantillons de biopsie sont traités n’a pas changé depuis 100 ans : ils sont découpés, fixés, incorporés, tranchés, colorés avec des colorants, placés sur une lame de verre et examinés par un pathologiste à l’aide d’un simple microscope. C’est pourquoi il faut parfois plusieurs jours avant d’avoir des nouvelles de votre diagnostic après une biopsie”, explique Elizabeth Hillman, professeur d’ingénierie biomédicale et de radiologie à Columbia University and senior author of the study.

Hillman’s group dreamed of a bold alternative, wondering whether they could capture images of the tissue while it is still within the body. “Such a technology could give a doctor real-time feedback about what type of tissue they are looking at without the long wait,” she explains. “This instant answer would let them make informed decisions about how best to cut out a tumor and ensure there is none left behind.”

Another major benefit of the approach is that cutting tissue out, just to figure out what it is, is a hard decision for doctors, especially for precious tissues such as the brain, spinal cord, nerves, the eye, and areas of the face. This means that doctors can miss important areas of disease. “Because we can image the living tissue, without cutting it out, we hope that MediSCAPE will make those decisions a thing of the past,” says Hillman.

Although some microscopes for surgical guidance are already available, they only give doctors an image of a small, single 2D plane, making it difficult to quickly survey larger areas of tissue and interpret results. These microscopes also generally require a fluorescent dye to be injected into the patient, which takes time and can limit their use for certain patients.

Over the past decade, Hillman, who is also Herbert and Florence Irving Professor at Columbia’s Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, has been developing new kinds of microscopes for neuroscience research that can capture very fast 3D images of living samples like tiny worms, fish, and flies to see how neurons throughout their brains and bodies fire when they move. The team decided to test whether their technology, termed SCAPE (for Swept Confocally Aligned Planar Excitation microscopy) could see anything useful in tissues from other parts of the body.

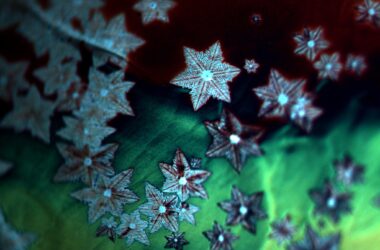

“One of the first tissues we looked at was fresh mouse kidney, and we were stunned to see gorgeous structures that looked a lot like what you get with standard histology,” says Kripa Patel, a recent PhD graduate from the Hillman lab and lead author of the study. “Most importantly, we didn’t add any dyes to the mouse –everything we saw was natural fluorescence in the tissue that is usually too weak to see. Our microscope is so efficient that we could see these weak signals well, even though we were also imaging whole 3D volumes at speeds fast enough to rove around in real time, scanning different areas of the tissue as if we were holding a flashlight.”

As she “roved around,” Patel could even stitch together the acquired volumes and turn the data into large 3D representations of the tissue that a pathologist could examine as if it were a full box of histology slides.

“This was something I didn’t expect — that I could actually look at structures in 3D from different angles,” says collaborator Dr. Shana Coley, a renal pathologist at Columbia University Medical Center who collaborated closely on the study. “We found many examples where we would not have been able to identify a structure from a 2D section on a histology slide, but in 3D we could clearly see its shape. In renal pathology in particular, where we routinely work with very limited amounts of tissue, the more information we can derive from the sample, the better for delivering more effective patient care.”

The team demonstrated the power of MediSCAPE for a wide range of applications, from analysis of pancreatic cancer in a mouse, to Coley’s interest in non-destructive, rapid evaluation of human transplant organs such as kidneys. Coley helped the team get fresh samples from human kidneys to prove that MediSCAPE could see telltale signs of kidney disease that matched well to conventional histology images.

The team also realized that by imaging tissues while they are alive in the body, they could get even more information than from lifeless excised biopsies. They found that they could actually visualize blood flow through tissues, and see the cellular-level effects of ischemia and reperfusion (cutting off the blood supply to the kidney and then letting it flow back in).

“Understanding whether tissues are staying healthy and getting good blood supply during surgical procedures is really important,” says Hillman. “We also realized that if we don’t have to remove (and kill) tissues to look at them, we can find many more uses for MediSCAPE, even to answer simple questions such as ‘what tissue is this?’ or to navigate around precious nerves. Both of these applications are really important for robotic and laparoscopic surgeries where surgeons are more limited in their ability to identify and interact with tissues directly.”

A critical final step for the team was to reduce the large format of the standard SCAPE microscopes in Hillman’s lab to something that would fit into an operating room and could be used by a surgeon in the human body. Post-doctoral fellow Wenxuan Liang worked with the team to develop a smaller version of the system with a better form factor, and a sterile imaging cap. PhD candidate Malte Casper helped to acquire the team’s first demonstration of MediSCAPE in a living human, collecting images of a range of tissues in and around the mouth. These results included rapidly imaging while a volunteer literally licked the end of the imaging probe, producing detailed 3D views of the papillae of the tongue.

Eager to take this technology to the next level with a larger clinical trial, the team is currently working on commercialization and FDA approval. Hillman adds, “We are just so amazed to see what MediSCAPE reveals every time we use it on a new tissue, and especially that we barely ever even needed to add dyes or stains to see structures that pathologists can recognize.”

Hillman and her team hopes that MediSCAPE will make standard histology a thing of the past, putting the power of real-time histology and decision making into the surgeon’s hands.

Reference: “High-speed light-sheet microscopy for the in-situ acquisition of volumetric histological images of living tissue” 28 March 2022, Nature Biomedical Engineering.

DOI: 10.1038/s41551-022-00849-7