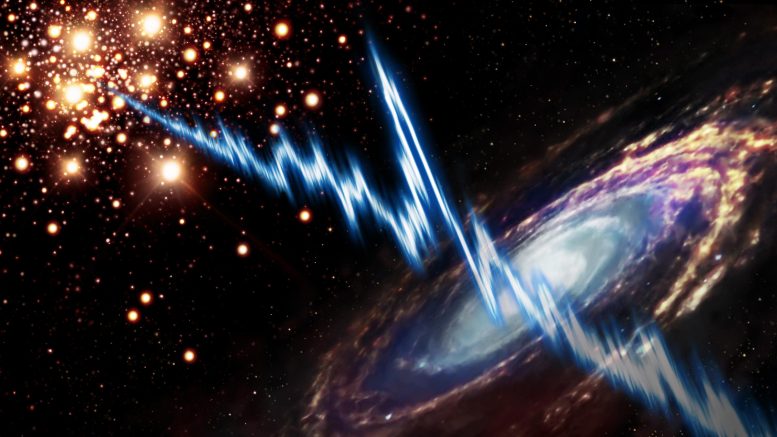

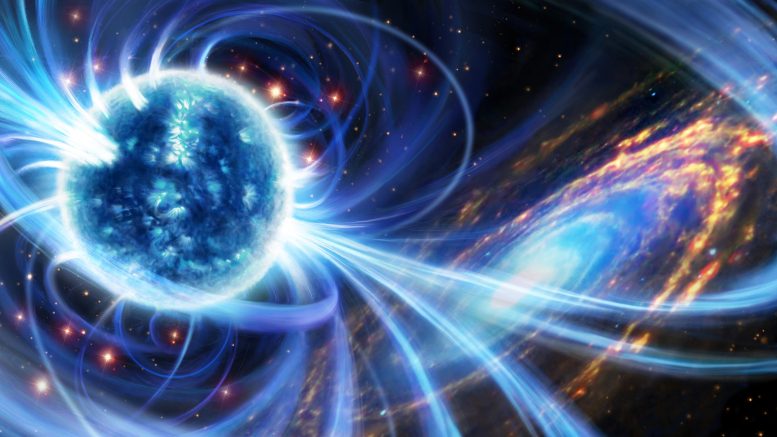

Des signaux radio extrêmement rapides provenant d’une source surprenante. Un amas d’étoiles anciennes (à gauche) proche de la galaxie spirale Messier 81 (M81) est la source de signaux radio extraordinairement brillants et courts. L’image montre en bleu-blanc un graphique de l’évolution de la luminosité d’un flash en l’espace de quelques dizaines de microsecondes seulement. Crédit : Daniëlle Futselaar, artsource.nl

Les Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) sont des éclats de rayonnement d’une durée de quelques millisecondes enregistrés sur les ondes radio. Ils sont extrêmement puissants – par exemple, pendant l’un des éclairs les plus brillants, d’une durée de cinq millisecondes, il se dégage autant d’énergie que notre Soleil en génère en un mois. L’ampleur du phénomène est difficile à imaginer.

Les premiers sursauts radio ont été “découverts” il y a à peine 15 ans. Jusqu’en avril 2020, tous les FRBs observés par les astronomes provenaient de distances cosmologiques de centaines de millions d’années-lumière. Ce n’est qu’il y a deux ans qu’ils ont également réussi à suivre des flashs provenant de notre Galaxie. Il est important de noter qu’en raison de l’équipement et de la limite de sensibilité associée, les chercheurs ne peuvent observer que les objets les plus lumineux de l’Univers, les sursauts les plus puissants.

“Lorsque nous avons vu les premiers résultats, nous n’avons pas pu y croire, et au début, nous avons même pensé que nous avions fait une erreur de calcul.” – Dr. Marcin Gawronski

“Les FRBs sont actuellement l’un des sujets les plus chauds de l’astrophysique contemporaine. Découverts accidentellement en 2007 lors d’un examen des données d’archives, et faisant actuellement l’objet d’une observation intensive, ils restent un grand mystère”, explique le Dr Marcin Gawronski de l’Institut d’astronomie de la Faculté de physique, d’astronomie et d’informatique de l’Université Nicolaus Copernicus (Torun, Pologne). “Les résultats rassemblés jusqu’à présent permettent de diviser les phénomènes FRB en différentes classes, mais nous n’avons toujours pas découvert s’ils sont l’émanation d’un seul ou de plusieurs processus physiques distincts.”

Prise cosmique

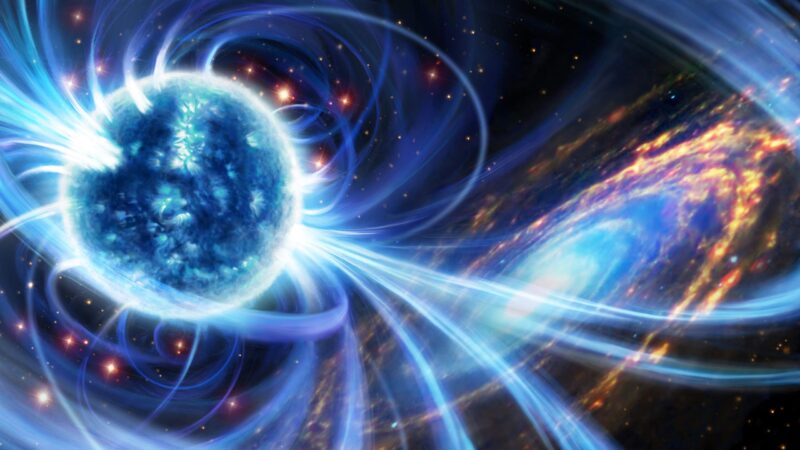

Les chercheurs ne sont pas sûrs à 100 % de la cause des sursauts. Les astrophysiciens ont diverses hypothèses qui pourraient expliquer leur formation, notamment l’existence de civilisations extraterrestres. Cependant, jusqu’à présent, les magnétars ont été considérés comme la source des FRBs.

Source de mystérieux signaux radio : une impression d’artiste d’un magnétar dans un amas d’étoiles anciennes (en rouge) près de la galaxie spirale Messier 81 (M81). Crédit : Daniëlle Futselaar, artsource.nl

” Les magnétars sont des étoiles à neutrons avec des champs magnétiques extrêmement puissants, ils se forment après des explosions de supernova “, explique le Dr Gawronski. “Jusqu’à présent, les scientifiques se sont accordés pour dire qu’ils sont responsables des FRBs. Pourquoi ? Parce que pour produire un FRB, il est nécessaire de disposer d’une énorme quantité d’énergie, qui peut être rapidement libérée et utilisée dans divers processus. Les seules sources de ce type que nous connaissons sont soit les champs magnétiques d’un amas d’étoiles à neutrons – ces magnétars – soit l’énergie gravitationnelle des trous noirs.”

Bien que les astronomes s’accordent à dire que les flashs radio rapides sont le résultat de processus violents qui se produisent dans le voisinage immédiat des étoiles à neutrons fortement magnétisées, on ne sait toujours pas pourquoi la plupart d’entre eux apparaissent comme des signaux uniques, alors que d’autres sources peuvent être observées sur les ondes radio de manière répétée. Dans certains cas, les sursauts sont en outre caractérisés par une activité périodique, c’est-à-dire qu’ils se produisent à intervalles de temps réguliers. Toutefois, cela n’aide qu’à planifier les observations.

Les astronomes doivent également faire face à un certain nombre de difficultés lors de l’observation des FRB. “L’étude de l’activité des FRB est très difficile car les flashs sont des phénomènes aléatoires. Cela ressemble un peu à la pêche – on lance une canne à pêche et on attend. Nous installons donc des radiotélescopes et nous devons attendre patiemment”, explique M. Gawronski. “Un autre problème est que les radiotélescopes “voient” un champ assez large du ciel, par exemple, le nôtre à Piwnice couvre une zone de la moitié de la taille du disque lunaire dans la bande radio, que nous utilisons habituellement pour les observations de FRB. Il y a beaucoup d’objets sur une si grande surface, il est donc difficile de localiser un flash particulier. Un autre problème est l’énorme quantité de données que nous recueillons lors de ces observations – nous pouvons enregistrer jusqu’à 4 gigabits de données par seconde, ce qui nécessite de très grandes capacités de stockage. Nous devons donc traiter, analyser et supprimer ces données en permanence pour faire de la place aux suivantes.”

Marcin Gawronski de l’Institut d’astronomie de la Faculté de physique, d’astronomie et d’informatique de l’Université Nicolaus Copernicus (Torun, Pologne). Crédit : Andrzej Romanski/NCU, Torun, Pologne.

Comme vousLancement en mars des options sur les contrats à terme Micro BTC et Micro ETH : CME

Selon un communiqué de presse publié sur PR Newswire, CME Group, la place de marché mondiale pour les produits dérivés, a été le premier à publier des contrats à terme BTC pour les institutions financières fin 2017 et a lancé des micro-futures sur la première et la deuxième plus grande cryptomonnaie en 2021.

Aujourd’hui, la société s’apprête à lancer des options sur cette dernière.

CME Group a annoncé qu’il prévoyait de lancer des options sur les contrats à terme Micro Bitcoin et Micro Ether le 28 mars, en attendant l’examen réglementaire. Les nouveaux contrats d’options Micro Bitcoin et Micro Ether représenteront un dixième de leurs jetons sous-jacents respectifs. https://t.co/3sWplDqYLv[{” attribute=””>Milky Way — it is located about 12 million light-years away from us, in summer when the weather is good you can see it with a regular set of binoculars, and e.g., with the Hubble telescope you can observe single stars in it,” explains Dr. Gawronski. “Canadians from the CHIME project told us that there was a source of fast radio bursts in the vicinity of this galaxy, and what’s more, some of its properties indicated that this object was related to the M81. We thought it would be a great opportunity to try to find out what specifically generated the FRBs.”

The observations were made by researchers working primarily in the PRECISE consortium.

“This is a team of researchers whose main objective is to locate FRB sources, estimate the distances to them, and study the properties of the environment in which FRBs are placed. In this way, we can try to say something about the evolution of the sources of fast bursts and the very processes in which FRB objects are generated,” says Dr. Gawronski. “In a sense, we act in parallel to EVN (European Very Long Baseline Interferometry Network), as we try to gather European radio telescopes outside the time allocated for standard observations within this consortium, to which, of course, the NCU Institute of Astronomy belongs together with the RT4 radio telescope.”

Dr. Marcin Gawronski from the Institute of Astronomy at the Faculty of Physics, Astronomy and Informatics Nicolaus Copernicus University (Torun, Poland). “In these observations, we used the largest European radio telescopes: a 100-meter dish in Effelsberg, Germany, and a 60-meter dish on Sardinia and RT4 in Piwnice,” says Dr. Gawronski. Credit: Andrzej Romanski/NCU, Torun, Poland

The researchers are very lucky. The first time they pointed their radio telescopes at the vicinity of the M81 galaxy, they found a series of four bursts. It wasn’t long before they caught two more. However, the new findings came as a surprise to the researchers.

“When we saw the first results, we could not believe it, and at first, we even thought that we had made a calculation error. It turned out that we had not. It was like in the Monty Python’s sketch ‘Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.’ Because none of us expected such a thing,” says Dr. Gawronski.

A young one among the old?

Firstly, the burst came from a globular cluster. So, the first disappointment came at the beginning — a cluster of this type consists of a huge number of densely packed stars, so it was impossible to pinpoint the specific object that was the source of the FRB, even with the help of the Hubble orbiting telescope. More interestingly, globular clusters are composed of very old stars, formed up to 10 billion years ago — they are the oldest star systems in the galaxies. It is therefore futile to look for “young” magnetars there.

“Many questions came to our minds: where did the magnetar come from there? We assumed that it must have been the source of the bursts. In fact, the magnetar could not have been there. And if it was, it could not have been formed in a classical way, i.e., following an explosion of a massive star,” explains Dr. Gawronski. “Such massive stars live for a very short time and within an estimated time of several tens of millions of years after their formation they end their lives in a very impressive phenomenon, called a supernova explosion. It is known that stars do not form in globular clusters for a long time, so no new magnetars can form there during a supernova phenomenon.”

– Wu Blockchain (@WuBlockchain)

1er mars 2022

Contrats d’options sur les contrats à terme Micro BTC et Micro ETH[{” attribute=””>white dwarf. Such a phenomenon can occur in a binary system, where a white dwarf slowly “eats” its companion and at some point, it exceeds the mass for which its stable structure can exist. Then this unstable dwarf explodes in a thermonuclear explosion, during which a neutron star may also be formed, such as a magnetar,” explains Dr. Gawronski. “However, it is not such a simple explanation: if there was a supernova explosion in a globular cluster (but of a different type than the death of massive stars), it must have happened not so long ago on a cosmic scale. According to current theories, magnetars are active for only a few million years after birth. The effects or remnants of such an explosion should be noticeable to us, but so far nothing has been observed.”

The other possible explanation is the merger of two compact, old stars — white dwarfs and/or neutron stars — and the formation of a young object in the so-called kilonova phenomenon. However, the chance of such an event occurring in our “local” Universe is rather slim.

The astronomers’ discovery is as interesting as it is mysterious. For now, one thing is certain — the bursts are the result of some as yet unrecognized phenomenon. The work of astrophysicists may contribute to its description and investigation. The results have been published in the prestigious journal Nature. The article “A repeating fast radio burst source in a globular cluster,” co-authored by Dr. Marcin Gawroñski, concerning the astronomers’ latest discovery is topic no. 1 in the latest issue of the journal.

What were the FRB observations like?

Researchers use the EVN infrastructure, primarily the huge disk capacities that were dedicated to the PRECISE consortium.

“We check which radio telescopes are available at a given time and apply for time — we organize this ad hoc, about 3-4 weeks in advance,” says Dr. Marcin Gawronski. “We have to connect at least five radio telescopes together, creating a network. In these observations we used the largest European radio telescopes: a 100-meter dish in Effelsberg, Germany, and a 60-meter dish on Sardinia. They are large and therefore have a significant collecting area, so we analyzed the data gathered by them first.”

After completing further series of observations, researchers must then study the recorded signal for the presence of FRBs as soon as possible, and inform the EVN stations that selected data can be deleted as irrelevant.

Recently, the system for observation, data collection and analysis has been improved. Firstly, the English e-MERLIN radio telescope network has granted up to 400 hours of availability of its instruments to the PRECISE. Secondly, and no less importantly, thanks to investments in equipment from the University Centre of Excellence “Astrophysics and Astrochemistry,” the researchers in Piwnice have the possibility to process and study the recorded signal autonomously through their radio telescope.

“You can say that I am giving some servers a hard time, as they are working practically non-stop, processing huge amounts of data,” says Dr. Gawronski. “Apart from the PRECISE project, there is also our internal research team monitoring the known sources of FRB. We conduct observations by means of three radio telescopes: our RT-4 from Piwnice near Torun, the Dutch Westerbork and the Swedish Onsala. Thanks to these additional observations, we study the activity of the known FRB sources at frequencies above 1.4 GHz. The addition of a local computing node should greatly expand the capabilities of our research team.”

References:

“A repeating fast radio burst source in a globular cluster” by F. Kirsten, B. Marcote, K. Nimmo, J. W. T. Hessels, M. Bhardwaj, S. P. Tendulkar, A. Keimpema, J. Yang, M. P. Snelders, P. Scholz, A. B. Pearlman, C. J. Law, W. M. Peters, M. Giroletti, Z. Paragi, C. Bassa, D. M. Hewitt, U. Bach, V. Bezrukovs, M. Burgay, S. T. Buttaccio, J. E. Conway, A. Corongiu, R. Feiler, O. Forssén, M. P. Gawronski, R. Karuppusamy, M. A. Kharinov, M. Lindqvist, G. Maccaferri, A. Melnikov, O. S. Ould-Boukattine, A. Possenti, G. Surcis, N. Wang, J. Yuan, K. Aggarwal, R. Anna-Thomas, G. C. Bower, R. Blaauw, S. Burke-Spolaor, T. Cassanelli, T. E. Clarke, E. Fonseca, B. M. Gaensler, A. Gopinath, V. M. Kaspi, N. Kassim, T. J. W. Lazio, C. Leung, D. Z. Li, H. H. Lin, K. W. Masui, R. Mckinven, D. Michilli, A. G. Mikhailov, C. Ng, A. Orbidans, U. L. Pen, E. Petroff, M. Rahman, S. M. Ransom, K. Shin, K. M. Smith, I. H. Stairs and W. Vlemmings, 23 February 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-04354-w

“Burst timescales and luminosities as links between young pulsars and fast radio bursts” by K. Nimmo, J. W. T. Hessels, F. Kirsten, A. Keimpema, J. M. Cordes, M. P. Snelders, D. M. Hewitt, R. Karuppusamy, A. M. Archibald, V. Bezrukovs, M. Bhardwaj, R. Blaauw, S. T. Buttaccio, T. Cassanelli, J. E. Conway, A. Corongiu, R. Feiler, E. Fonseca, O. Forssén, M. Gawronski, M. Giroletti, M. A. Kharinov, C. Leung, M. Lindqvist, G. Maccaferri, B. Marcote, K. W. Masui, R. Mckinven, A. Melnikov, D. Michilli, A. G. Mikhailov, C. Ng, A. Orbidans, O. S. Ould-Boukattine, Z. Paragi, A. B. Pearlman, E. Petroff, M. Rahman, P. Scholz, K. Shin, K. M. Smith, I. H. Stairs, G. Surcis, S. P. Tendulkar, W. Vlemmings, N. Wang, J. Yang and J. P. Yuan, 23 February 2022, Nature Astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-021-01569-9

Les nouvelles options viendront compléter les options Bitcoin lancées il y a deux ans et dont la taille est de cinq BTC