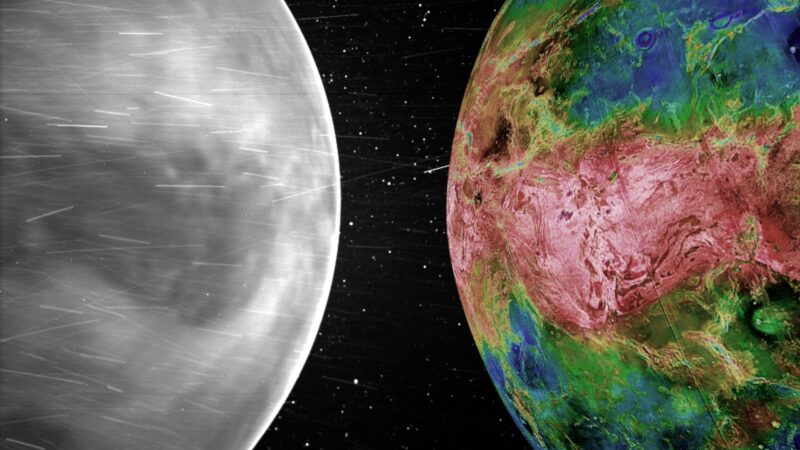

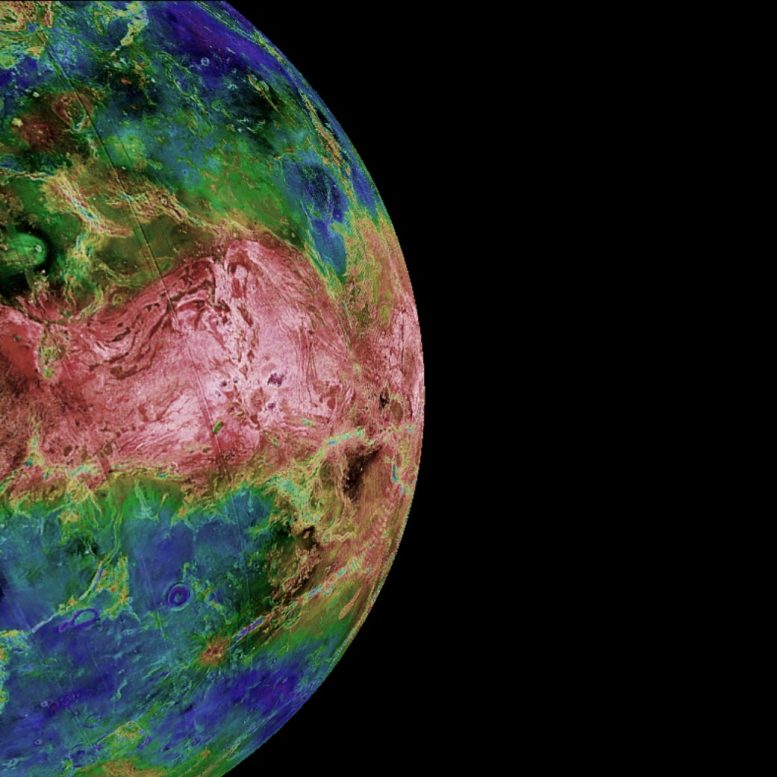

;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Parker Solar Probe has taken its first visible light images of the surface of Venus from space.

Smothered in thick clouds, Venus’ surface is usually shrouded from sight. But in two recent flybys of the planet, Parker used its Wide-Field Imager, or WISPR, to image the entire nightside in wavelengths of the visible spectrum – the type of light that the human eye can see – and extending into the near-infrared.

In the time since Parker Solar Probe captured its first visible light images of Venus’ surface from orbit in July 2020, a subsequent flyby has allowed the spacecraft to gather more images, creating a video of Venus’ entire nightside. A full analysis of the images and video, published on Feb. 9, 2022, in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, is adding to scientists’ understanding of the planet likened as Earth’s twin.

The images, combined into a video, reveal a faint glow from the surface that shows distinctive features like continental regions, plains, and plateaus. A luminescent halo of oxygen in the atmosphere can also be seen surrounding the planet.

“We’re thrilled with the science insights Parker Solar Probe has provided thus far,” said Nicola Fox, division director for the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters. “Parker continues to outperform our expectations, and we are excited that these novel observations taken during our gravity assist maneuver can help advance Venus research in unexpected ways.”

Such images of the planet, often called Earth’s twin, can help scientists learn more about Venus’ surface geology, what minerals might be present there, and the planet’s evolution. Given the similarities between the planets, this information can help scientists on the quest to understand why Venus became inhospitable and Earth became an oasis.

“Venus is the third brightest thing in the sky, but until recently we have not had much information on what the surface looked like because our view of it is blocked by a thick atmosphere,” said Brian Wood, lead author on the new study and physicist at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC. “Now, we finally are seeing the surface in visible wavelengths for the first time from space.”

La sonde Parker Solar Probe de la NASA a pris ses premières images en lumière visible de la surface de Vénus depuis l’espace. Crédit : Centre de vol spatial Goddard de la NASA/Joy Ng

Des capacités inattendues

Les premières images WISPR de Vénus ont été prises en juillet 2020, alors que Parker s’engageait dans son troisième survol, que la sonde spatiale utilise pour courber son orbite plus près du Soleil. Le WISPR a été conçu pour voir les caractéristiques faibles de l’atmosphère et du vent solaires, et certains scientifiques ont pensé qu’ils pourraient être en mesure d’utiliser le WISPR pour imager les sommets des nuages qui voilent Vénus lorsque Parker passe devant la planète.

“L’objectif était de mesurer la vitesse des nuages”, a déclaré le scientifique du projet WISPR, Angelos Vourlidas, co-auteur du nouvel article et chercheur au laboratoire de physique appliquée de l’université Johns Hopkins.

Mais au lieu de voir uniquement des nuages, le WISPR a également vu la surface de la planète. Les images étaient si frappantes que les scientifiques ont rallumé les caméras lors du quatrième passage en février 2021. Lors du survol de 2021, l’orbite du vaisseau spatial s’est parfaitement alignée pour permettre au WISPR de prendre des images de la partie nocturne de Vénus dans son intégralité.

“Les images et les vidéos m’ont tout simplement époustouflé”, a déclaré M. Wood.

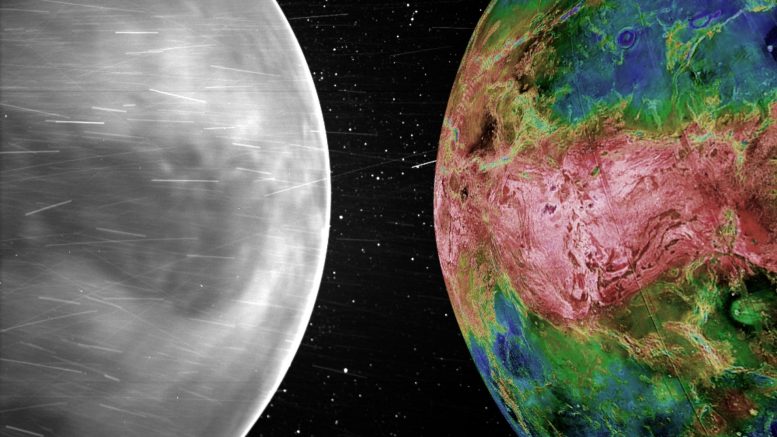

Lors du quatrième survol de Vénus par Parker Solar Probe, l’instrument WISPR a capturé ces images, assemblées en une vidéo, montrant la surface nocturne de la planète. Crédit : NASA/APL/NRL

Brillant comme un fer sorti de la forge

Les nuages obstruent la majeure partie de la lumière visible provenant de la surface de Vénus, mais les plus grandes longueurs d’onde visibles, à la limite des longueurs d’onde du proche infrarouge, parviennent à passer. De jour, cette lumière rouge se perd parmi les rayons du soleil qui se reflètent sur les sommets des nuages de Vénus, mais dans l’obscurité de la nuit, les caméras du WISPR ont pu capter cette faible lueur causée par l’incroyable chaleur émanant de la surface.

“La surface de Vénus, même du côté de la nuit, est à environ 860 degrés”, a déclaré M. Wood. “Il fait si chaud que la surface rocheuse de Vénus brille visiblement, comme un morceau de fer sorti d’une forge”.

En passant près de Vénus, WISPR a capté une gamme de longueurs d’onde allant de 470 nanomètres à 800 nanomètres. Une partie de cette lumière se trouve dans l’infrarouge proche – des longueurs d’onde que nous ne pouvons pas voir, mais que nous percevons comme de la chaleur – et une autre partie se trouve dans le domaine visible, entre 380 nanomètres et environ 750 nanomètres.

Vénus sous un nouveau jour

En 1975, l’atterrisseur Venera 9 a envoyé les premiers aperçus alléchants de la surface de Vénus après son atterrissage. Depuis lors, la surface de Vénus a été révélée par des instruments radar et infrarouges, qui peuvent scruter les épais nuages en utilisant des longueurs d’onde de lumière invisibles à l’œil humain. La mission Magellan de la NASA a créé les premières cartes dans les années 1990 à l’aide de radars et de JAXA’s Akatsuki spacecraft gathered infrared images after reaching orbit around Venus in 2016. The new images from Parker add to these findings by extending the observations to red wavelengths at the edge of what we can see.

The WISPR images show features on the Venusian surface, such as the continental region Aphrodite Terra, the Tellus Regio plateau, and the Aino Planitia plains. Since higher altitude regions are about 85 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than lower areas, they show up as dark patches amidst the brighter lowlands. These features can also be seen in previous radar images, such as those taken by Magellan.

Surface features seen in the WISPR images match ones seen in those from the Magellan mission (below). Credit: NASA/APL/NRL

Beyond looking at surface features, the new WISPR images will help scientists better understand the geology and mineral make-up of Venus. When heated, materials glow at unique wavelengths. By combining the new images with previous ones, scientists now have a wider range of wavelengths to study, which can help identify what minerals are on the surface of the planet. Such techniques have previously been used to study the surface of the Moon. Future missions will continue to expand this range of wavelengths, which will contribute to our understanding of habitable planets.

Surface features seen in the WISPR images (above) match ones seen in those from the Magellan mission here. Credit: Magellan Team/JPL/USGS

This information could also help scientists understand the planet’s evolution. While Venus, Earth, and Mars all formed around the same time, they are very different today. The atmosphere on Mars is a fraction of Earth’s while Venus has a much thicker atmosphere. Scientists suspect volcanism played a role in creating the dense Venusian atmosphere, but more data are needed to know how. The new WISPR images might provide clues about how volcanos may have affected the planet’s atmosphere.

In addition to the surface glow, the new images show a bright ring around the edge of the planet caused by oxygen atoms emitting light in the atmosphere. Called airglow, this type of light is also present in Earth’s atmosphere, where it’s visible from space and sometimes from the ground at night.

Flyby Science

While Parker Solar Probe’s primary goal is solar science, the Venusian flybys are providing exciting opportunities for bonus data that wasn’t expected at the mission’s launch.

WISPR has also imaged Venus’ orbital dust ring – a doughnut-shaped track of microscopic particles strewn in the wake of Venus’ orbit around the Sun – and the FIELDS instrument made direct measurements of radio waves in the Venusian atmosphere, helping scientists understand how the upper atmosphere changes during the Sun’s 11-year cycle of activity.

In December 2021, researchers published new findings about the rediscovery of the comet-like tail of plasma streaming out behind Venus, called a “tail ray”. The new results showed this tail of particles extending nearly 5,000 miles out from the Venusian atmosphere. This tail could be how Venus’ water escaped from the planet, contributing to its current dry and inhospitable environment.

While the geometry of the next two flybys likely won’t allow Parker to image the nightside, scientists will continue to use Parker’s other instruments to study Venus’ space environment. In November 2024, the spacecraft will have a final chance to image the surface on its seventh and final flyby.

The Future of Venus Research

Parker Solar Probe, which is built and operated by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, isn’t the first mission to gather bonus data on flybys, but its recent successes have inspired other missions to turn on their instruments as they pass Venus. In addition to Parker, the ESA (European Space Agency) BepiColombo mission and the ESA and NASA Solar Orbiter mission have decided to gather data during their flybys in the coming years.

More spacecraft are headed to Venus around the end of this decade with NASA’s DAVINCI and VERITAS missions and ESA’s EnVision mission. These missions will help image and sample Venus’ atmosphere, as well as remap the surface at higher resolution with infrared wavelengths. This information will help scientists determine the surface mineral make-up and better understand the planet’s geologic history.

“By studying the surface and atmosphere of Venus, we hope the upcoming missions will help scientists understand the evolution of Venus and what was responsible for making Venus inhospitable today,” said Lori Glaze, director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters. “While both DAVINCI and VERITAS will use primarily near-infrared imaging, Parker’s results have shown the value of imaging a wide range of wavelengths.”