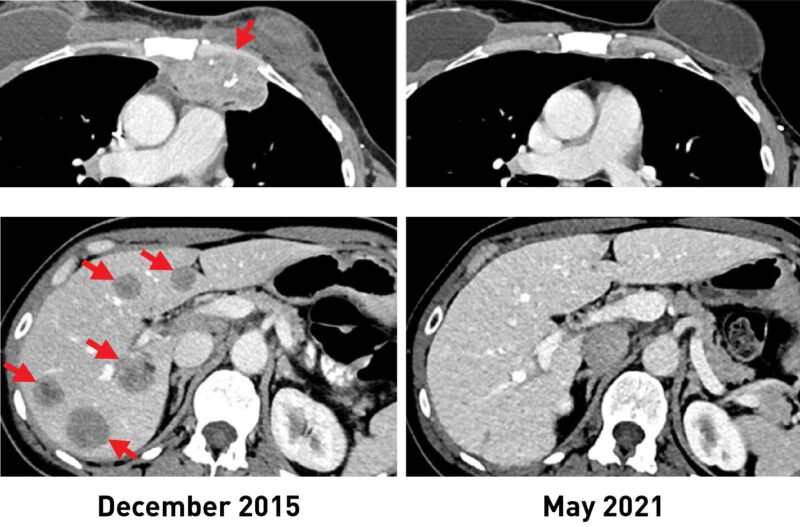

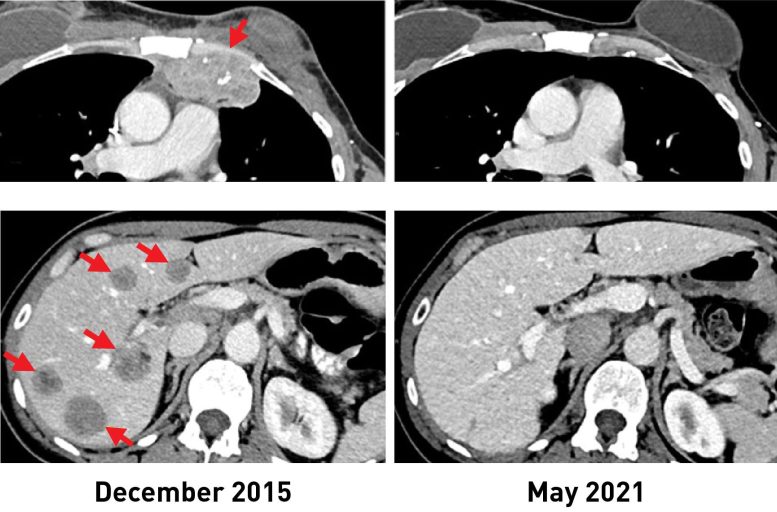

Une femme atteinte d’un cancer du sein présentait des lésions métastatiques dans la paroi thoracique (en haut, à gauche) et le foie (en bas, à gauche). Après avoir reçu l’immunothérapie, les tumeurs ont complètement rétréci. Des scanners récents (R) montrent qu’elle n’a plus de cancer plus de 5 ans après. Crédit : Institut national du cancer (NCI)

Une forme expérimentale d’immunothérapie qui utilise les cellules immunitaires d’un individu combattant les tumeurs pourrait potentiellement être utilisée pour traiter les personnes atteintes d’un cancer du sein métastatique, selon les résultats d’un essai clinique en cours dirigé par des chercheurs du Centre de recherche sur le cancer du National Cancer Institute (NCI), qui fait partie des National Institutes of Health. L’étude a révélé que de nombreuses personnes atteintes d’un cancer du sein métastatique sont capables d’organiser une réaction immunitaire contre leurs tumeurs, ce qui constitue une condition préalable à ce type d’immunothérapie, qui repose sur ce que l’on appelle les lymphocytes infiltrant les tumeurs (TIL).

Dans un essai clinique portant sur 42 femmes atteintes d’un cancer du sein métastatique, 28 (soit 67 %) ont généré une réaction immunitaire contre leur cancer. Cette approche a été utilisée pour traiter six femmes, dont la moitié a connu une réduction mesurable de la tumeur. Les résultats de l’essai sont parus le 1er février 2022 dans la revue Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“C’est un dogme populaire que les cancers du sein à récepteurs hormonaux positifs ne sont pas capables de provoquer une réponse immunitaire et ne sont pas sensibles à l’immunothérapie”, a déclaré le chef de l’étude Steven A. Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., chef de la branche chirurgicale du Centre de recherche sur le cancer du NCI. “Ces résultats suggèrent que cette forme d’immunothérapie peut être utilisée pour traiter certaines personnes atteintes d’un cancer du sein métastatique qui ont épuisé toutes les autres options thérapeutiques.”

L’immunothérapie est un traitement qui aide le système immunitaire d’une personne à combattre le cancer. Cependant, la plupart des immunothérapies disponibles, comme les inhibiteurs de points de contrôle immunitaire, ont montré une efficacité limitée contre les cancers du sein à récepteurs hormonaux positifs, qui constituent la majorité des cancers du sein.

L’approche d’immunothérapie utilisée dans l’essai a été mise au point à la fin des années 1980 par le Dr Rosenberg et ses collègues du NCI. Elle s’appuie sur les TIL, des cellules T qui se trouvent dans et autour de la tumeur.

Les TIL peuvent cibler les cellules tumorales qui ont des protéines spécifiques à leur surface, appelées néoantigènes, que les cellules immunitaires reconnaissent. Les néoantigènes sont produits lorsque des mutations se produisent dans les cellules tumorales DNA. Other forms of immunotherapy have been found to be effective in treating cancers, such as melanoma, that have many mutations, and therefore many neoantigens. Its effectiveness in cancers that have fewer neoantigens, such as breast cancer, however, has been less clear.

The results of the new study come from an ongoing phase 2 clinical trial being carried out by Dr. Rosenberg and his colleagues. This trial was designed to see if the immunotherapy approach could lead to tumor regressions in people with metastatic epithelial cancers, including breast cancer. In 2018, the researchers showed that one woman with metastatic breast cancer who was treated in this trial had complete tumor shrinkage, known as a complete response.

In the trial, the researchers used whole-genome sequencing to identify mutations in tumor samples from 42 women with metastatic breast cancer whose cancers had progressed despite all other treatments. The researchers then isolated TILs from the tumor samples and, in lab tests, tested their reactivity against neoantigens produced by the different mutations in the tumor.

Twenty-eight women had TILs that recognized at least one neoantigen. Nearly all the neoantigens identified were unique to each patient.

“It’s fascinating that the Achilles’ heel of these cancers can potentially be the very gene mutations that caused the cancer,” said Dr. Rosenberg. “Since that 2018 study, we now have information on 42 patients, showing that the majority give rise to immune reactions.”

For the six women treated, the researchers took the reactive TILs and grew them to large numbers in the lab. They then returned the immune cells to each patient via intravenous infusion. All the patients were also given four doses of the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) before the infusion to prevent the newly introduced T cells from becoming inactivated.

After the treatment, tumors shrank in three of the six women. One is the original woman reported in the 2018 study, who remains cancer free to this day. The other two women had tumor shrinkage of 52% and 69% after six months and 10 months, respectively. However, some disease returned and was surgically removed. Those women now have no evidence of cancer approximately five years and 3.5 years, respectively, after their TIL treatment.

The researchers acknowledged that the use of pembrolizumab, which has been approved for some early-stage breast cancers, may raise uncertainties about its influence on the outcome of TIL therapy. However, they said, treatment with such checkpoint inhibitors alone has not led to sustained tumor shrinkage in people with hormone receptor–positive metastatic breast cancer.

Dr. Rosenberg said that with the anticipated opening early this year of NCI’s new building devoted to cell-based therapies, he and his colleagues can begin treating more individuals with metastatic breast cancer as part of the ongoing clinical trial. He noted that this new immunotherapy approach could potentially be used for people with other types of cancer as well.

“We’re using a patient’s own lymphocytes as a drug to treat the cancer by targeting the unique mutations in that cancer,” he said. “This is a highly personalized treatment.”

Reference: “Breast Cancers are immunogenic: Immunologic analyses and a phase II pilot clinical trial using mutation-reactive lymphocytes” 1 February 2022, Journal of Clinical Oncology.