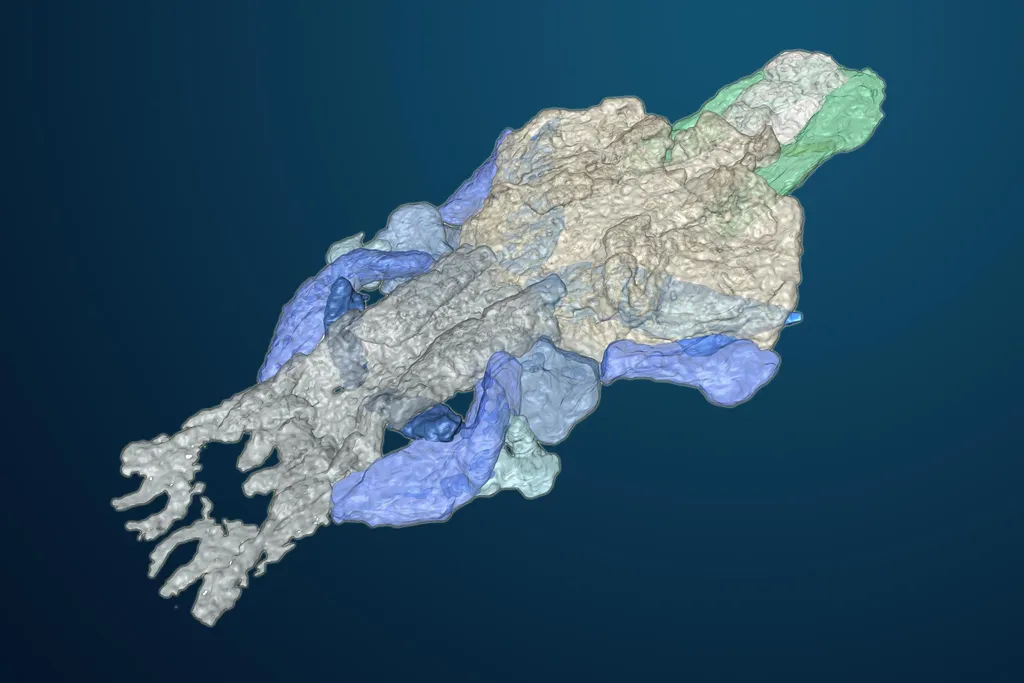

Reconstitution d’un paléospondylus par tomographie à rayons X avec rayonnement synchrotron. Crédit : RIKEN

Preuve que le mystérieux vertébré ancien ressemblant à un poisson… Palaeospondylus était probablement l’un des premiers ancêtres des animaux à quatre membres, y compris les humains, a été découvert par le laboratoire de morphologie évolutive dirigé par Shigeru Kuratani au RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research (CPR) au Japon, avec des collaborateurs. Publié aujourd’hui (25 mai 2022) dans la revue scientifique Nature, l’étude démasque cet étrange animal du passé profond et fixe sa position sur l’arbre de l’évolution.

Palaeospondylus était un petit vertébré ressemblant à un poisson, d’environ 5 cm (2 pouces) de long, dont le corps ressemblait à celui d’une anguille et qui vivait au Dévonien, il y a environ 390 millions d’années. Bien que les fossiles soient abondants, sa petite taille et la piètre qualité des reconstitutions crâniennes – par tomodensitométrie et modèles en cire – ont rendu difficile son positionnement sur l’arbre de l’évolution depuis sa découverte en 1890. On pense qu’il partage des caractéristiques avec des poissons à mâchoires et sans mâchoires, et son corps reste un mystère pour les spécialistes de l’évolution. Parmi plusieurs caractéristiques inhabituelles, la plus déroutante est l’absence de dents ou d’os dermiques dans les archives fossiles.

Pour résoudre certaines de ces questions, les chercheurs ont utilisé l’incroyablement puissant RIKEN Super P& ; lt;/u>hoton ring& ; gt;-8 GeV" ;. Il appartient à RIKEN et est situé à Harima Science Garden City, dans la préfecture de Hyogo, au Japon.

;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>SPring-8 synchrotron to generate high-resolution micro-CT scans using synchrotron radiation X-rays. Furthermore, unlike most studies that have used excavated fossil heads, the new study used carefully selected fossils in which the heads remained completely embedded in the rock. “Choosing the best specimens for the micro-CT scans and carefully trimming away the rock surrounding the fossilized skull allowed us to improve the resolution of the scans,” says lead author Tatsuya Hirasawa. “Although not quite cutting-edge technology, these preparations were certainly keys to our achievement.”

The high-resolution scans revealed multiple important features. First, researchers discovered three semi-circular canals, clearly indicating an inner-ear morphology of jawed vertebrates. This resolved an issue because previous studies suggested that Palaeospondylus was evolutionarily closer to primitive jawless vertebrates. Next, they found key cranial features that place Palaeospondylus into the tetrapodomorph category, which is made from tetrapods—four-limbed animals—and their closest ancient relatives. Several analyses revealed that Palaeospondylus was more closely related to limbed tetrapods than to many other known tetrapodomorphs that still retained fins.

However, unlike tetrapodomorphs in general, teeth, dermal bones, and paired appendages have never been associated with Palaeospondylus fossils, although these features are readily found in fossils of other animals that lived around the same time and in the same place in the Achanarras fish bed in Scotland. The lack of these features can be explained by the splitting of a set of developmental features, resulting in a larval-like body. “Whether these features were evolutionarily lost or whether normal development froze halfway in fossils might never be known,” says Hirasawa. “Nevertheless, this heterochronic evolution might have facilitated the development of new features like limbs.”

Kuratani and his research group do not limit their study of early vertebrate evolution to the fossil record. They also use molecular biology and genetics to study developing embryos of key modern vertebrates. “The strange morphology of Palaeospondylus, which is comparable to that of tetrapod larvae, is very interesting from a developmental genetic point of view,” says Hirasawa. “Taking this into consideration, we will continue to study the developmental genetics that brought about this and other morphological changes that occurred at the water-to-land transition in vertebrate history.”

Reference: “Morphology of Palaeospondylus shows affinity to tetrapod ancestors” by Hirasawa T, Hu Y, Uesugi K, Hoshino M, Manabe M, Kuratani S, 25 May 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04781-3