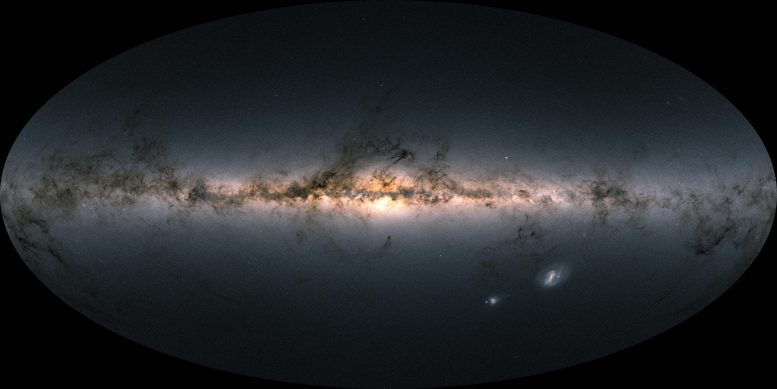

Les données de plus de 1,8 milliard d’étoiles ont été utilisées pour créer cette carte du ciel entier. Elle montre la luminosité totale et la couleur des étoiles observées par le satellite Gaia de l’ESA et publiées dans le cadre de Gaia Early Data Release 3 (Gaia EDR3). Les régions plus lumineuses représentent des concentrations plus denses d’étoiles brillantes, tandis que les régions plus sombres correspondent à des zones du ciel où l’on observe des étoiles moins nombreuses et plus faibles. Crédit : ESA/Gaia/DPAC ; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO, Remerciements : A. Moitinho

Grâce aux données de la mission Gaia de l’ESA, les astronomes ont montré qu’une partie de la Milky Way known as the ‘thick disc’ began forming 13 billion years ago, around 2 billion years earlier than expected, and just 0.8 billion years after the Big Bang.

This surprising result comes from an analysis performed by Maosheng Xiang and Hans-Walter Rix, from the Max-Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany. They took brightness and positional data from Gaia’s Early Data Release 3 (EDR3) dataset and combined it with measurements of the stars’ chemical compositions, as given by data from China’s Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST) for roughly 250,000 stars to derive their ages.

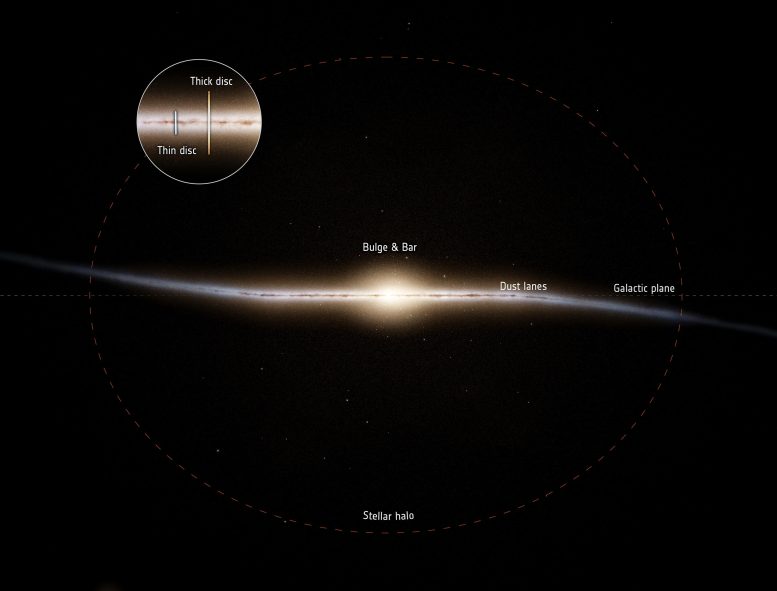

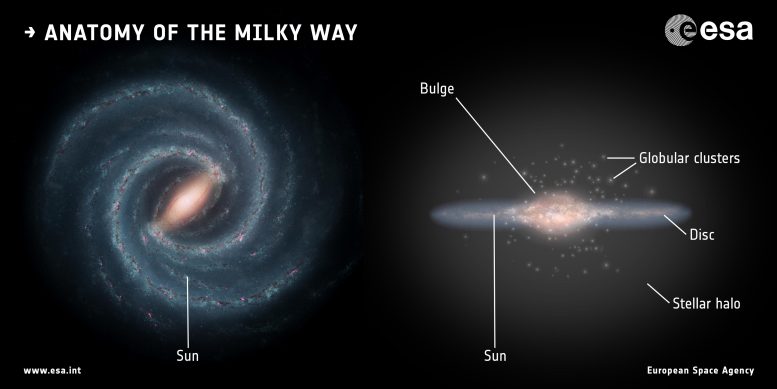

Basic structure of our home galaxy, edge-on view. The new results from ESA’s Gaia mission provide for a reconstruction of the history of the Milky Way, in particular of the evolution of the so-called thick disc. Credit: Stefan Payne-Wardenaar / MPIA

They chose to look at sub giant stars. In these stars, energy has stopped being generated in the star’s core and has moved into a shell around the core. The star itself is transforming into a red giant star. Because the sub giant phase is a relatively brief evolutionary phase in a star’s life, it permits its age to be determined with great accuracy, but it’s still a tricky calculation.

How old are the stars?

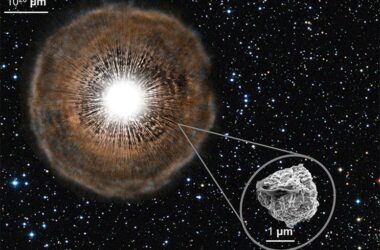

The age of a star is one of the most difficult parameters to determine. It cannot be measured directly but must be inferred by comparing a star’s characteristics with computer models of stellar evolution. The compositional data helps with this. The Universe was born with almost exclusively hydrogen and helium. The other chemical elements, known collectively as metals to astronomers, are made inside stars, and exploded back into space at the end of a star’s life, where they can be incorporated into the next generation of stars. So, older stars have fewer metals and are said to have lower metallicity.

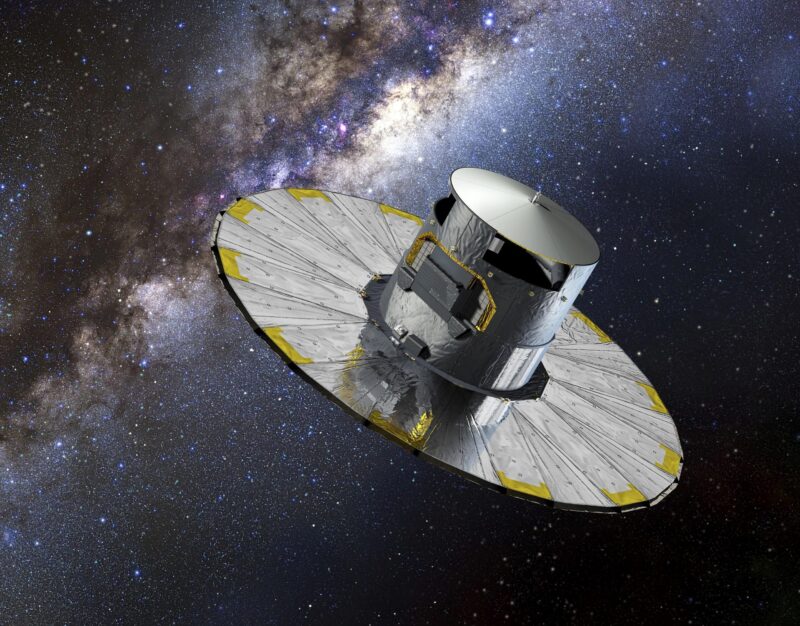

Artist’s impression of the Gaia spacecraft. Credit: ESA–D. Ducros, 2013

The LAMOST data gives the metallicity. Together, the brightness and metallicity allow astronomers to extract the star’s age from the computer models. Before Gaia, astronomers were routinely working with uncertainties of 20-40 percent, which could result in the determined ages being imprecise by a billion years or more.

Gaia’s EDR3 data release changes this. “With Gaia’s brightness data, we are able to determine the age of a sub giant star to a few percent,” says Maosheng. Armed with precise ages for a quarter of a million sub giant stars spread throughout the galaxy, Maosheng and Hans-Walter began the analysis.

An artist’s impression of our Milky Way galaxy, a roughly 13 billon-year-old ‘barred spiral galaxy’ that is home to a few hundred billion stars. Credit: Left: NASA/JPL-Caltech; right: ESA; layout: ESA/ATG medialab

Milky Way anatomy

Our galaxy is made of different components. Broadly, these can be split into the halo and the disc. The halo is the spherical region surrounding the disc, and has traditionally been thought to be the oldest component of the galaxy. The disc is composed of two parts: the thin disc and the thick disc. The thin disc contains most of the stars that we see as the misty band of light in the night sky that we call the Milky Way. The thick disc is more than double the height of the thin disc but smaller in radius, containing only a few per cent of the Milky Way’s stars in the solar neighborhood.

By identifying sub giant stars in these different regions, the researchers were able to build a timeline of the Milky Way’s formation – and that’s when they got a surprise.

Two phases in Milky Way history

The stellar ages clearly revealed that the formation of the Milky Way fell into two distinct phases. In the first phase, starting just 0.8 billion years after the Big Bang, the thick disc began forming stars. The inner parts of the halo may also have begun to come together at this stage, but the process rapidly accelerated to completion about two billion years later when a dwarf galaxy known as Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus merged with the Milky Way. It filled the halo with stars and, as clearly revealed by the new work, triggered the nascent thick disc to form the majority of its stars. The thin disc of stars which holds the Sun, was formed during the subsequent, second phase of the galaxy’s formation.

The analysis also shows that after the star-forming burst triggered by the merger with Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus, the thick disc continued to form stars until the gas was used up at around 6 billion years after the Big Bang. During this time, the metallicity of the thick disk grew by more than a factor of 10. But remarkably, the researchers see a very tight stellar age—metallicity relation, which indicates that throughout that period, the gas forming the stars was well-mixed across the whole disk. This implies that the early Milky Way’s disk regions must have been formed from highly turbulent gas that effectively spread the metals far and wide.

Une ligne du temps grâce à Gaia

L’âge de formation plus précoce du disque épais pointe vers une image différente de l’histoire précoce de notre galaxie. “Depuis la découverte de l’ancienne fusion avec Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus, en 2018, les astronomes soupçonnent que la Voie lactée était déjà là avant la formation du halo, mais nous n’avions pas d’image claire de ce à quoi ressemblait cette Voie lactée. Nos résultats fournissent des détails exquis sur cette partie de la Voie lactée, comme son anniversaire, son taux de formation d’étoiles et son histoire d’enrichissement en métaux. La mise en commun de ces découvertes à l’aide des données Gaia révolutionne notre vision du moment et de la manière dont notre galaxie s’est formée”, déclare Maosheng.

Et nous ne regardons peut-être pas encore assez loin dans l’Univers pour voir des disques galactiques similaires se former. Un âge de 13 milliards d’années correspond à un décalage vers le rouge de 7, le décalage vers le rouge étant une mesure de la distance à laquelle se trouve un objet céleste, et donc du temps que sa lumière a mis pour traverser l’espace et nous atteindre.

De nouvelles observations pourraient voir le jour dans un avenir proche grâce au James Webb Space Telescope has been optimized to see the earliest Milky Way-like galaxies in the Universe. And on June 13 this year, Gaia will release its full third data release (Gaia DR3). This catalog will include spectra and derived information like ages and metallicity, making studies like Maosheng’s even easier to conduct.

“With each new analysis and data release, Gaia allows us to piece together the history of our galaxy in even more unprecedented detail. With the release of Gaia DR3 in June, astronomers will be able to enrich the story with even more details,” says Timo Prusti, Gaia Project Scientist for ESA.

Reference: “A time-resolved picture of our Milky Way’s early formation history” by Maosheng Xiang and Hans-Walter Rix, 23 March 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04496-5