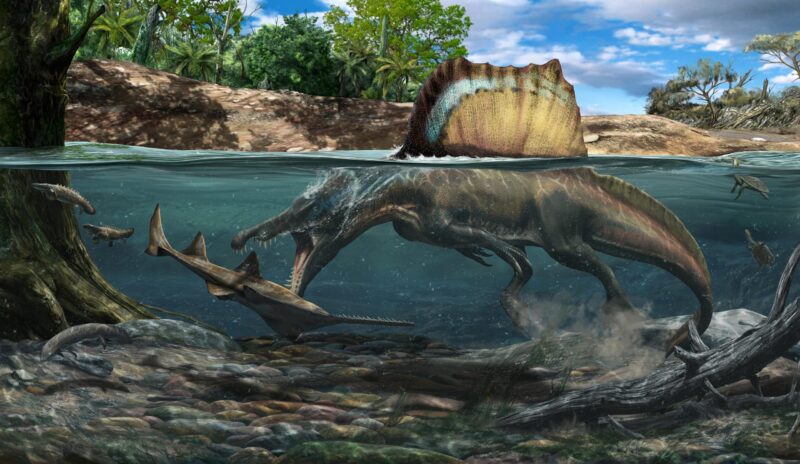

Spinosaurus, le plus long dinosaure prédateur connu, ouvre ses mâchoires allongées, constellées de dents coniques, pour attraper une scie. Contrairement à ce qui avait été suggéré, cet animal n’était pas un échassier ressemblant à un héron – c’était un “monstre des rivières”, qui poursuivait activement ses proies dans un vaste système fluvial situé dans l’actuelle Afrique du Nord. Les os denses du squelette de Spinosaurus suggèrent fortement qu’il passait beaucoup de temps immergé dans l’eau. Crédit : Davide Bonadonna

Son proche cousin Baryonyx nageait probablement aussi, mais Suchomimus aurait pu patauger comme un héron.

Spinosaurus est le plus grand dinosaure carnivore jamais découvert, encore plus grand que le . T. rex-mais la façon dont il chassait fait l’objet de débats depuis des décennies. Il est difficile de deviner le comportement d’un animal que nous ne connaissons qu’à partir de fossiles. Spinosaurus pouvait nager, mais d’autres pensent qu’il se contentait de patauger dans l’eau comme un héron. Comme l’examen de l’anatomie des dinosaures spinosauridés n’a pas suffi à résoudre le mystère, un groupe de paléontologues publie une nouvelle étude dans la revue Nature qui adopte une approche différente : l’examen de la densité de leurs os. En analysant la densité des os de spinosauridés et en les comparant à celle d’autres animaux comme les pingouins, les hippopotames et les alligators, l’équipe a constaté que Spinosaurus et son proche parent Baryonyx avaient des os denses qui leur auraient probablement permis de s’immerger sous l’eau pour chasser. Pendant ce temps, un autre dinosaure apparenté appelé Suchomimus avait des os plus légers qui auraient rendu la nage plus difficile. Il était donc probable qu’il pataugeait ou passait plus de temps sur la terre ferme comme les autres dinosaures.

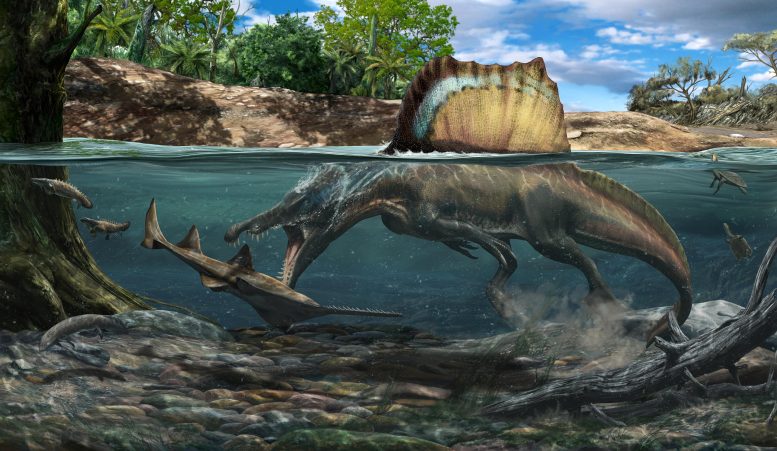

Le Baryonyx, originaire du Surrey en Angleterre, nage dans une ancienne rivière avec un poisson dans ses mâchoires. Comme son parent africain Spinosaurus, beaucoup plus grand, Baryonyx avait des os denses, ce qui suggère qu’il passait lui aussi une grande partie de son temps immergé dans l’eau. On pensait auparavant qu’il était moins aquatique que son parent saharien. Crédit : Davide Bonadonna

“Le registre fossile est délicat – parmi les spinosauridés, il n’y a qu’une poignée de squelettes partiels, et nous n’avons aucun squelette complet pour ces dinosaures “, explique Matteo Fabbri, chercheur postdoctoral au Field Museum et auteur principal de l’étude dans l’article intitulé Nature. “D’autres études se sont concentrées sur l’interprétation de l’anatomie, mais il est clair que s’il y a des interprétations aussi opposées concernant les mêmes os, c’est déjà un signal clair que peut-être ce ne sont pas les meilleurs proxies pour nous permettre de déduire l’écologie des animaux éteints.”

Toute vie est initialement venue de l’eau, et la plupart des groupes de vertébrés terrestres contiennent des membres qui y sont retournés – par exemple, alors que la plupart des mammifères sont terrestres, nous avons des baleines et des phoques qui vivent dans l’océan, et d’autres mammifères comme les loutres, les tapirs et les hippopotames qui sont semi-aquatiques. Les oiseaux ont des pingouins et des cormorans ; les reptiles ont des alligators, des crocodiles, des iguanes marins et des serpents de mer. Pendant longtemps, les dinosaures non aviaires (les dinos qui ne se sont pas ramifiés en oiseaux) étaient le seul groupe qui ne comptait aucun habitant de l’eau. Cela a changé en 2014, quand une nouvelleSpinosaurus squelette a été décrit par Nizar Ibrahim au University of Portsmouth.

Lead author Matteo Fabbri doing fieldwork. Credit: Diego Mattarelli

Scientists already knew that spinosaurids spent some time by water—their long, croc-like jaws and cone-shaped teeth are similar to other aquatic predators’, and some fossils had been found with bellies full of fish. But the new Spinosaurus specimen described in 2014 had retracted nostrils, short hind legs, paddle-like feet, and a fin-like tail: all signs that pointed to an aquatic lifestyle. But researchers have continued to debate whether spinosaurids actually swam for their food or if they just stood in the shallows and dipped their heads in to snap up prey. This continued back-and-forth led Fabbri and his colleagues to try to find another way to solve the problem.

“The idea for our study was, okay, clearly we can interpret the fossil data in different ways. But what about the general physical laws?” says Fabbri. “There are certain laws that are applicable to any organism on this planet. One of these laws regards density and the capability of submerging into water.”

Simone Maganuco (middle), Davide Bonadonna (right) and lead author Matteo Fabbri (left) organizing fossils at night. Credit: Nanni Fontana

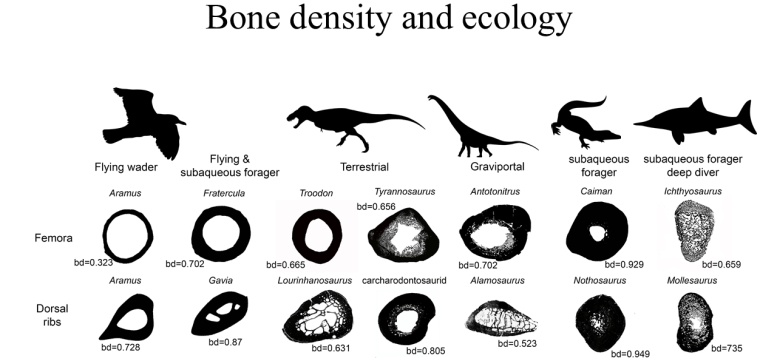

Across the animal kingdom, bone density is a tell in terms of whether that animal is able to sink beneath the surface and swim. “Previous studies have shown that mammals adapted to water have dense, compact bone in their postcranial skeletons,” says Fabbri. Dense bone works as buoyancy control and allows the animal to submerge itself.

“We thought, okay, maybe this is the proxy we can use to determine if spinosaurids were actually aquatic,” says Fabbri.

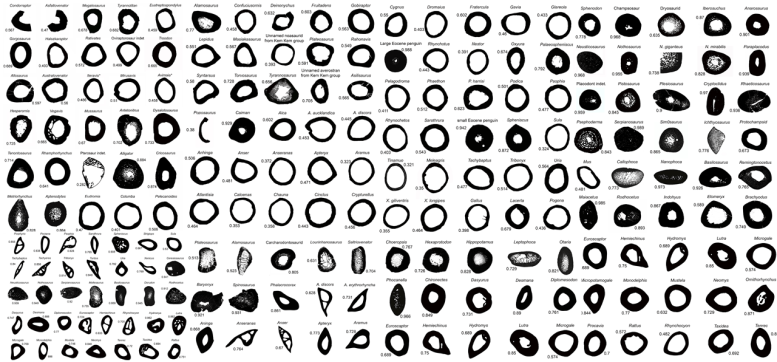

Fabbri and his colleagues, including co-corresponding authors Guillermo Navalón at Cambridge University and Roger Benson at Oxford University, put together a dataset of femur and rib bone cross-sections from 250 species of extinct and living animals, both land-dwellers and water-dwellers. The researchers compared these cross-sections to cross-sections of bone from Spinosaurus and its relatives Baryonyx and Suchomimus. “We had to divide this study into successive steps,” says Fabbri. “The first one was to understand if there is actually a universal correlation between bone density and ecology. And the second one was to infer ecological adaptations in extinct taxa” Essentially, the team had to show a proof of concept among animals that are still alive that we know for sure are aquatic or not, and then applied them to extinct animals that we can’t observe.

Figure from paper showing relationship between bone density and ecology. Credit: Fabbri et al

When selecting animals to include in the study, the researchers cast a wide net. “We were looking for extreme diversity,” says Fabbri. “We included seals, whales, elephants, mice, hummingbirds. We have dinosaurs of different sizes, extinct marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. We have animals that weigh several tons, and animals that are just a few grams. The spread is very big.”

This menagerie of animals revealed a clear link between bone density and aquatic foraging behavior: animals that submerge themselves underwater to find food have bones that are almost completely solid throughout, whereas cross-sections of land-dwellers’ bones look more like donuts, with hollow centers. “There is a very strong correlation, and the best explanatory model that we found was in the correlation between bone density and sub-aqueous foraging. This means that all the animals that have the behavior where they are fully submerged have these dense bones, and that was the great news,” says Fabbri.

Figure from paper comparing animals’ bone densities. Credit: Fabbri et al

When the researchers applied spinosaurid dinosaur bones to this paradigm, they found that Spinosaurus and Baryonyx both had the sort of dense bone associated with full submersion. Meanwhile, the closely related Suchomimus had hollower bones. It still lived by water and ate fish, as evidenced by its crocodile-mimic snout and conical teeth, but based on its bone density, it wasn’t actually swimming.

Other dinosaurs, like the giant long-necked sauropods also had dense bones, but the researchers don’t think that meant they were swimming. “Very heavy animals like elephants and rhinos, and like the sauropod dinosaurs, have very dense limb bones, because there’s so much stress on the limbs,” explains Fabbri. “That being said, the other bones are pretty lightweight. That’s why it was important for us to look at a variety of bones from each of the animals in the study.” And while there are limitations to this kind of analysis, Fabbri is excited by the potential for this study to tell us about how dinosaurs lived.

“One of the big surprises from this study was how rare underwater foraging was for dinosaurs, and that even among spinosaurids, their behavior was much more diverse that we’d thought,” says Fabbri.

Jingmai O’Connor, a curator at the Field Museum and co-author of this study, says that collaborative studies like this one that draw from hundreds of specimens, are “the future of paleontology. They’re very time-consuming to do, but they let scientists shed light onto big patterns, rather than making qualitative observations based on one fossil. It’s really awesome that Matteo was able to pull this together, and it requires a lot of patience.”

Fabbri also notes that the study shows how much information can be gleaned from incomplete specimens. “The good news with this study is that now we can move on from the paradigm where you need to know as much as you can about the anatomy of a dinosaur to know about its ecology, because we show that there are other reliable proxies that you can use. If you have a new species of dinosaur and you just have only a few bones of it, you can create a dataset to calculate bone density, and at least you can infer if it was aquatic or not.”

Reference: “Subaqueous foraging among carnivorous dinosaurs” by Matteo Fabbri, Guillermo Navalón, Roger B. J. Benson, Diego Pol, Jingmai O’Connor, Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, Gregory M. Erickson, Mark A. Norell, Andrew Orkney, Matthew C. Lamanna, Samir Zouhri, Justine Becker, Amanda Emke, Cristiano Dal Sasso, Gabriele Bindellini, Simone Maganuco, Marco Auditore and Nizar Ibrahim, 23 March 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04528-0