Utilisation du grand réseau millimétrique/submillimétrique d’Atacama (ALMA) in Chile, researchers at Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands have for the first time detected dimethyl ether in a planet-forming disc. With nine atoms, this is the largest molecule identified in such a disc to date. It is also a precursor of larger organic molecules that can lead to the emergence of life.

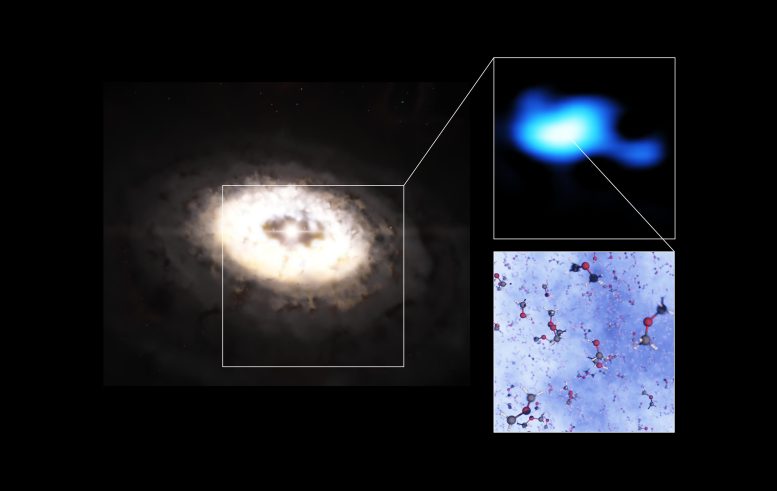

This composite image features an artistic impression of the planet-forming disc around the IRS 48 star, also known as Oph-IRS 48. The disc contains a cashew-nut-shaped region in its southern part, which traps millimeter-sized dust grains that can come together and grow into kilometer-sized objects like comets, asteroids, and potentially even planets. Recent observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) spotted several complex organic molecules in this region, including dimethyl ether, the largest molecule found in a planet-forming disc to date. The emission signaling the presence of this molecule (real observations shown in blue) is clearly stronger in the disc’s dust trap. A model of the molecule is also shown in this composite. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada, ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/A. Pohl, van der Marel et al., Brunken et al.

“From these results, we can learn more about the origin of life on our planet and therefore get a better idea of the potential for life in other planetary systems. It is very exciting to see how these findings fit into the bigger picture,” says Nashanty Brunken, a Master’s student at Leiden Observatory, part of Leiden University, and lead author of the study published on March 8, 2022, in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Comment les ingrédients de la vie se retrouvent-ils sur les planètes ? La découverte de la plus grande molécule jamais trouvée dans un disque de formation de planète fournit des indices. Crédit : ESO

Dimethyl ether is an organic molecule commonly seen in star-forming clouds, but had never before been found in a planet-forming disc. The researchers also made a tentative detection of methyl formate, a complex molecule similar to dimethyl ether that is also a building block for even larger organic molecules.

“It is really exciting to finally detect these larger molecules in discs. For a while we thought it might not be possible to observe them,” says co-author Alice Booth, also a researcher at Leiden Observatory.

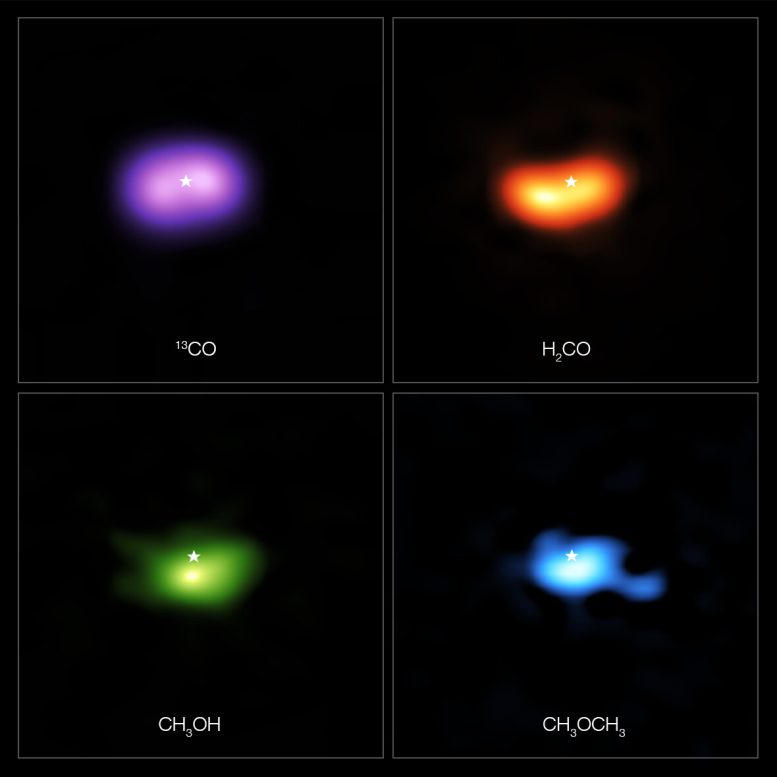

These images from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) show where various gas molecules were found in the disc around the IRS 48 star, also known as Oph-IRS 48. The disc contains a cashew-nut-shaped region in its southern part, which traps millimeter-sized dust grains that can come together and grow into kilometer-sized objects like comets, asteroids and potentially even planets. Recent observations spotted several complex organic molecules in this region, including formaldehyde (H2CO; orange), methanol (CH3OH; green), and dimethyl ether (CH3OCH3; blue), the last being the largest molecule found in a planet-forming disc to date. The emission signaling the presence of these molecules is clearly stronger in the disc’s dust trap, while carbon monoxide gas (CO; purple) is present in the entire gas disc. The location of the central star is marked with a star in all four images. The dust trap is about the same size as the area taken up by the methanol emission, shown on the bottom left. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/A. Pohl, van der Marel et al., Brunken et al.

The molecules were found in the planet-forming disc around the young star IRS 48 (also known as Oph-IRS 48) with the help of ALMA, an observatory co-owned by the European Southern Observatory (ESO). IRS 48, located 444 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus, has been the subject of numerous studies because its disc contains an asymmetric, cashew-nut-shaped “dust trap.” This region, which likely formed as a result of a newly born planet or small companion star located between the star and the dust trap, retains large numbers of millimeter-sized dust grains that can come together and grow into kilometer-sized objects like comets, asteroids and potentially even planets.

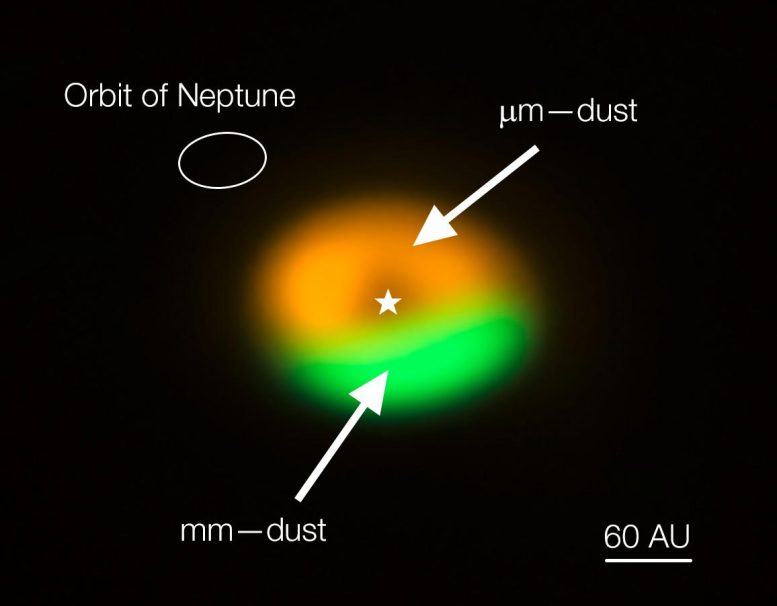

Annotated image from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) showing the dust trap in the disc that surrounds the system Oph-IRS 48. The dust trap provides a safe haven for the tiny dust particles in the disc, allowing them to clump together and grow to sizes that allow them to survive on their own. The green area is the dust trap, where the bigger particles accumulate. The size of the orbit of Neptune is shown in the upper left corner to show the scale. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Nienke van der Marel

Many complex organic molecules, such as dimethyl ether, are thought to arise in star-forming clouds, even before the stars themselves are born. In these cold environments, atoms and simple molecules like carbon monoxide stick to dust grains, forming an ice layer and undergoing chemical reactions, which result in more complex molecules. Researchers recently discovered that the dust trap in the IRS 48 disc is also an ice reservoir, harboring dust grains covered with this ice rich in complex molecules. It was in this region of the disc that ALMA has now spotted signs of the dimethyl ether molecule: as heating from IRS 48 sublimates the ice into gas, the trapped molecules inherited from the cold clouds are freed and become detectable.

Cette vidéo fait un zoom sur le système Oph-IRS 48, une étoile entourée d’un disque de formation de planètes qui contient un piège à poussière. Ce piège permet aux particules de poussière de grandir et de donner naissance à des corps plus gros.

“Ce qui rend cette découverte encore plus passionnante, c’est que nous savons maintenant que ces molécules complexes plus grandes sont disponibles pour nourrir les planètes en formation dans le disque”, explique Booth. “Cela n’était pas connu auparavant car dans la plupart des systèmes, ces molécules sont cachées dans la glace”.

La découverte de l’éther diméthylique suggère que de nombreuses autres molécules complexes qui sont couramment détectées dans les régions de formation d’étoiles peuvent également se cacher sur les structures glacées des disques de formation de planètes. Ces molécules sont les précurseurs de molécules prébiotiques telles que

;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>amino acids and sugars, which are some of the basic building blocks of life.

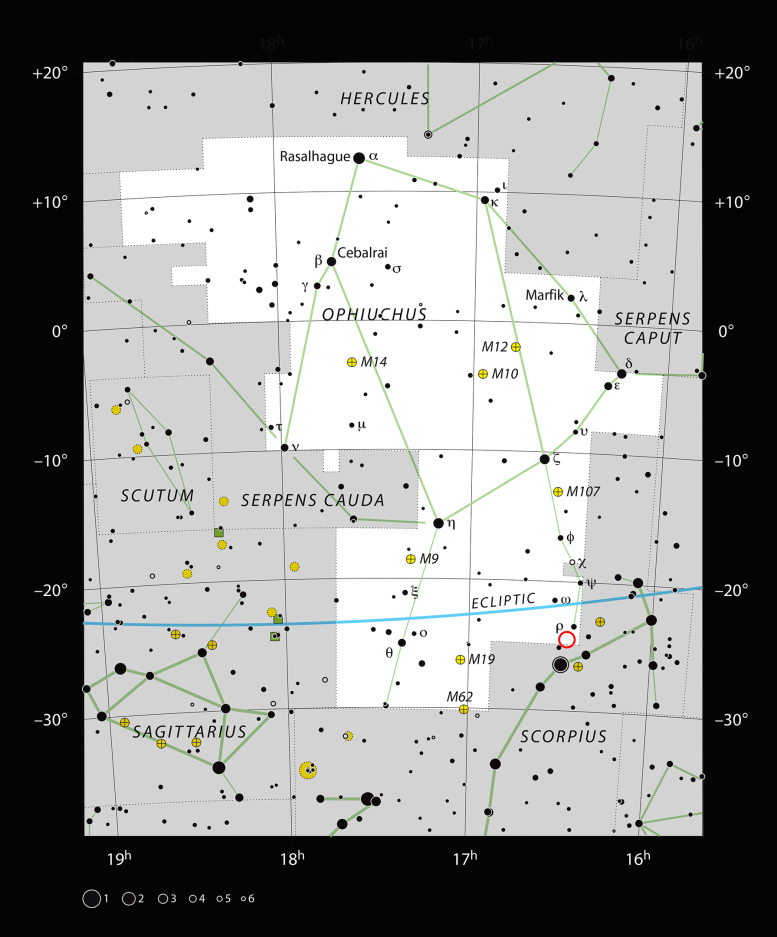

This chart shows the large constellation of Ophiuchus (The Serpent Bearer). Most of the stars that can be seen in a dark sky with the unaided eye are marked. The location of the system Oph-IRS 48 is indicated with a red circle. Credit: ESO, IAU and Sky & Telescope

By studying their formation and evolution, researchers can therefore gain a better understanding of how prebiotic molecules end up on planets, including our own. “We are incredibly pleased that we can now start to follow the entire journey of these complex molecules from the clouds that form stars, to planet-forming discs, and to comets. Hopefully, with more observations we can get a step closer to understanding the origin of prebiotic molecules in our own Solar System,” says Nienke van der Marel, a Leiden Observatory researcher who also participated in the study.

Cette vidéo fait un zoom sur le système Oph-IRS 48, une étoile entourée d’un disque de formation de planètes qui contient un piège à poussière. Ce piège permet aux particules de poussière de grandir et de donner naissance à des corps plus gros.

Les études futures de l’IRS 48 avec le télescope ELT (Extremely Large Telescope) de l’ESO, actuellement en construction au Chili et dont l’exploitation devrait commencer dans le courant de la décennie, permettront à l’équipe d’étudier la chimie des régions très internes du disque, où des planètes comme la Terre pourraient se former.

Référence : “Un piège à glace asymétrique majeur dans un disque de formation de planètes : III. First detection of dimethyl ether” par Nashanty G. C. Brunken, Alice S. Booth, Margot Leemker, Pooneh Nazari, Nienke van der Marel et Ewine F. van Dishoeck, 8 mars 2022, Astronomie et astrophysique.

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202142981

Cette publication a été publiée à l’occasion de la Journée internationale de la femme 2022 et présente des recherches menées par six chercheurs qui s’identifient comme des femmes.

L’équipe est composée de Nashanty G. C. Brunken (Observatoire de Leyde, Université de Leyde, Pays-Bas). [Leiden]), Alice S. Booth (Leiden), Margot Leemker (Leiden), Pooneh Nazari (Leiden), Nienke van der Marel (Leiden), Ewine F. van Dishoeck (Observatoire de Leiden, Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Garching, Allemagne).