Les astronomes ont découvert une étoile, appelée HD 222925, qui possède la plus large gamme d’éléments jamais observée dans une étoile au-delà de notre propre Soleil. Ils ont identifié 65 éléments dans l’étoile, dont 42 provenant du bas du tableau périodique.

Une équipe d’astronomes dirigée par Ian Roederer, de l’Université du Michigan, et comprenant Erika Holmbeck, de Carnegie, a identifié la plus large gamme d’éléments encore observés dans une étoile au-delà de notre propre Soleil. Leurs résultats seront publiés dans The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

Les chercheurs ont identifié 65 éléments dans l’étoile, qui s’appelle HD 222925. Parmi ceux-ci, 42 sont issus du bas du tableau périodique. Leur identification aidera les astronomes à mieux comprendre le processus de capture rapide des neutrons – l’une des principales méthodes par lesquelles les éléments lourds de l’univers ont été créés.

“À ma connaissance, c’est un record pour tout objet situé au-delà de notre système solaire. Et ce qui rend cette étoile si unique, c’est qu’elle présente une proportion relative très élevée des éléments énumérés dans les deux tiers inférieurs du tableau périodique. Nous avons même détecté de l’or”, a expliqué M. Roederer, un ancien post-doctorant de Carnegie. “Ces éléments ont été fabriqués par le processus de capture rapide des neutrons. C’est vraiment la chose que nous essayons d’étudier : la physique pour comprendre comment, où et quand ces éléments ont été fabriqués.”

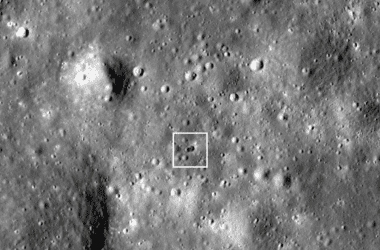

L’étoile HD 222925 est une étoile de neuvième magnitude située vers la constellation sud de Tucana. Crédit : The STScI Digitized Sky Survey.

De nombreux éléments sont formés par fusion nucléaire, au cours de laquelle deux noyaux atomiques fusionnent et libèrent de l’énergie, créant un atom. But elements heavier than zinc are made by a process called neutron capture, during which an existing element acquires additional neutrons one at a time that then “decay” into protons, changing the makeup of the atom into a new element.

Neutrons can be captured slowly, over long periods of time inside the star, or in a matter of seconds, when a catastrophic event causes a burst of neutrons to bombard an area. Different types of elements are created by each method. But it’s the second one that’s of interest to this research.

“Astronomers debated for many years about what phenomena could trigger such a bombardment and in 2017 it was confirmed that heavy elements could be created by the collision of two neutron stars—a discovery in which Carnegie astronomers played a crucial role,” Holmbeck said. “Certain types of supernovae could possibly also produce these heavy elements, but that remains to be observationally confirmed.”

Holmbeck is working on a follow-up paper to determine whether the chemical abundances observed in HD 222925 were formed by a neutron star merger or a supernova.

“The additional elements identified in this study provide a new baseline that can be compared to simulations, which we can use to reveal the origin story of the heavy elements seen in HD 222925’s unique chemical signature.”

The material the team identified in HD 222925 was synthesized very early in the universe’s youth. It was ejected and thrown back into space, where it later reformed into the star they were studying. This means that HD 222925 can be used as a proxy for what a neutron star merger or supernova would have produced.

Crucially, the astronomers used an instrument on the Hubble Space Telescope that can collect ultraviolet spectra. This was key in allowing the astronomers to collect light in the ultraviolet part of the light spectrum—light that is faint, coming from a cool star such as HD 222925. The astronomers also used one of the Magellan telescopes at Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile to collect light from HD 222925 in the optical part of the light spectrum.

These spectra encode the “chemical fingerprint” of elements within stars, and reading these spectra allows the astronomers not only to identify the elements contained in the star, but also how much of an element the star contains.

“We now know the detailed element-by-element output of some r-process event that happened early in the universe,” said co-author Anna Frebel of MIT. “Any model that tries to understand what’s going on with the r-process has to be able to reproduce that.”

Many of the study co-authors are part of a group called the R-Process Alliance, a group of astrophysicists dedicated to solving the big questions of the r-process. This project marks one of the team’s key goals: identifying which elements, and in what amounts, were produced in the r-process in an unprecedented level of detail.

Reference: “The R-Process Alliance: A Nearly Complete R-Process Abundance Template Derived from Ultraviolet Spectroscopy of the R-Process-Enhanced Metal-Poor Star HD 222925” by Ian U. Roederer, James E. Lawler, Elizabeth A. Den Hartog, Vinicius M. Placco, Rebecca Surman, Timothy C. Beers, Rana Ezzeddine, Anna Frebel, Terese T. Hansen, Kohei Hattori, Erika M. Holmbeck and Charli M. Sakari, Accepted, The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

arXiv:2205.03426

This work was supported by NASA through grants from the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Incorporated, under a NASA contract; the U.S. National Science Foundation; the NASA Astrophysics Data Analysis Program; the U.S. Department of Energy, and NOIRLab, which is managed by AURA under a cooperative agreement with the NSF.