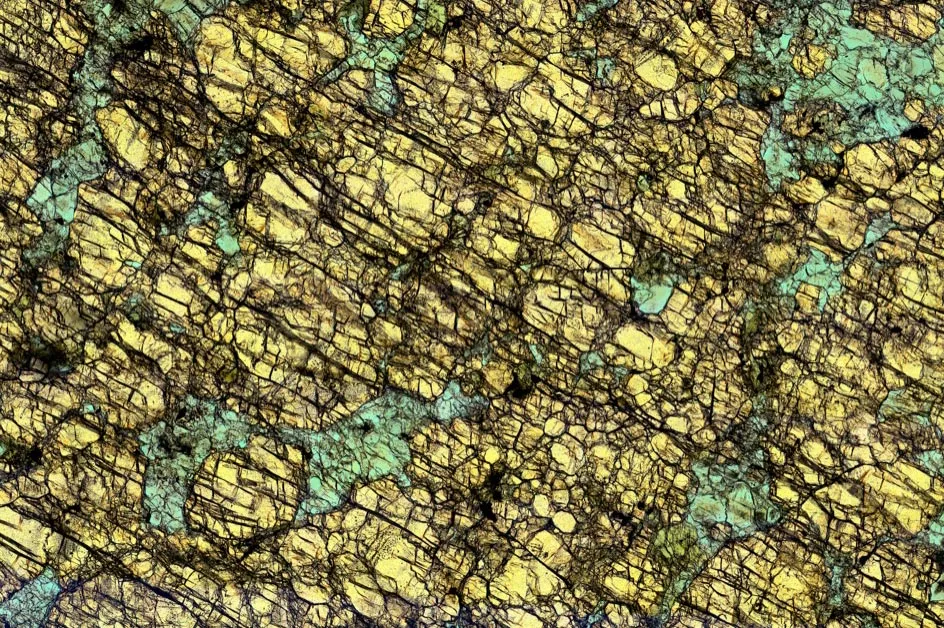

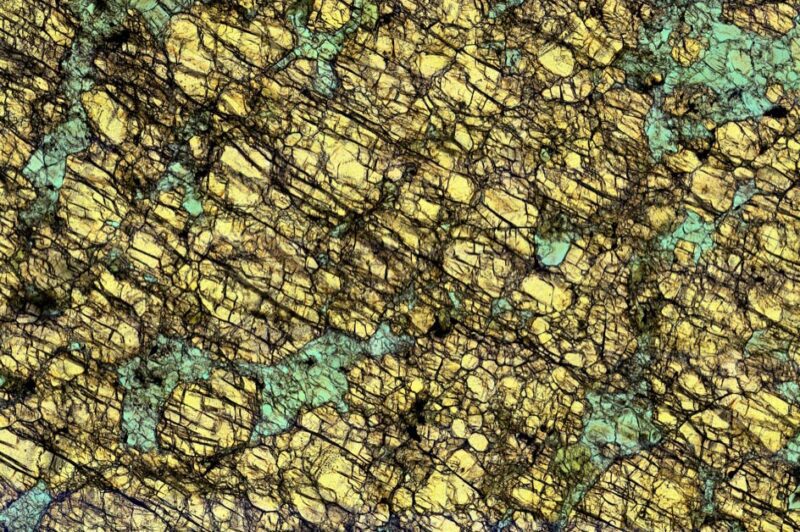

Photographie au microscope d’une roche crustale de l’arc inférieur utilisée dans l’étude, montrant des minéraux de grenat (rouge) et de clinopyroxène (vert). Crédit : avec l’aimable autorisation des chercheurs

Le magma sous les zones de collision tectonique est plus humide qu’on ne le pensait auparavant

De nouveaux résultats de recherche pourraient aider à expliquer la formation de la croûte terrestre, l’emplacement des gisements de minerai et pourquoi certains volcans sont plus explosifs que d’autres.

Une nouvelle étude a découvert que les plaques continentales qui entrent en collision peuvent aspirer plus d’eau qu’on ne le pensait auparavant. Ces résultats pourraient contribuer à expliquer l’explosivité de certaines éruptions volcaniques, ainsi que la répartition des gisements de minerais tels que le cuivre, l’argent et l’or. Les recherches ont été menées par des géologues de la Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), MIT, and elsewhere.

The findings are based on an analysis of ancient magmatic rocks recovered from the Himalayan mountains — a geologic formation that is the product of a subduction zone, where two massive tectonic plates have crushed against each other, one plate sliding beneath the other over millions of years.

Subduction zones can be found around the world. As one tectonic plate slides beneath another, it can take ocean water with it, drawing it deep into the mantle, where the liquid can merge with rising magma. The more water magma contains, the more explosive an eruption may be. Subduction zones, therefore, are the sites of some of the strongest and most destructive volcanic eruptions in the world.

Rocks rich in the minerals garnet (red) and amphibole (black) from the Kohistan paleo-arc, similar to samples analyzed in the present study (hammer shown for scale). Credit: Courtesy of Othmar Müntener

Their analysis, published on May 26, 2022, in the journal Nature Geoscience, finds that magma at subduction zones, or “arc magmas,” can contain up to 20 percent water content by weight — about double the maximum water content that has been widely assumed. The new estimate suggests that subduction zones draw down more water than previously thought, and that arc magmas are “super-hydrous,” and much wetter than scientists had estimated.

The study’s authors include lead author Ben Urann PhD ’21, who was a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program at the time of the study (now at the University of Wyoming); Urann’s PhD advisor Véronique Le Roux of WHOI and the MIT-WHOI Joint Program; Oliver Jagoutz, professor of geology in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences; Othmar Müntener of the University of Lausanne in Switzerland; Mark Behn of Boston College; and Emily Chin of Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Deep bends

Previously, estimating the amount of water drawn down in subduction zones was done by analyzing volcanic rocks that have erupted to the surface. Scientists measured signatures of water in these rocks and then reconstructed the rocks’ original water content, when they first absorbed the liquid as magma, deep beneath the Earth’s crust. These estimates suggested that magma contains about 4 percent water by weight on average.

But Urann and Le Roux questioned these analyses: What if there are processes the rising magma undergoes that affect the original water content in a way that scientists did not anticipate?

“The question was, are these rocks that rose quickly and erupted representative of what’s really going on down deep, or is there some surface process that skews those numbers?” Urann says.

Benjamin Urann, who graduated from the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in 2021 and is now a NSF postdoctoral fellow at U of Wyoming, analyzes water in minerals with a secondary ion mass spectrometer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Credit: Benjamin Urann

Taking a different approach, the team looked to ancient magmatic rocks called plutons, that remained deep beneath the surface, never having erupted in the first place. These rocks, they reasoned, would be more pristine recorders of the water they originally absorbed.

Urann and Le Roux developed new analytical methods by secondary ion mass spectrometry at WHOI to analyze water in plutons collected previously by Jagoutz and Müntener in the Kohistan arc — a region of the western Himalayan mountains comprising a large geologic section of rock that crystallized long ago. This material was subsequently upheaved to the surface, exposing layers of preserved, unerupted plutons, or magmatic rock.

“These are incredibly fresh rocks,” Urann says. “There is no evidence of the rocks’ crystals being disturbed in any way, so that was the driver for using these samples.”

Urann and Le Roux selected the freshest samples and analyzed them for signs of water. They combined water measurements with the composition of minerals in each crystal and plugged these numbers into an equation to back-calculate the amount of water that must have been absorbed originally by magma, just before it crystallized into its rock form.

In the end, their calculations revealed that the arc magmas contained an original water content of more than 8 percent by weight.

The team’s new estimates may help to explain why volcanic eruptions in some parts of the world are stronger and more explosive than others.

“This water content is key to understanding why arc magmas are more explosive,” says Cin-Ty Lee, professor of geology at Rice University who was not involved in the research. “The water content of arc magmas is a bit of a mystery because it’s so hard to reconstruct original water content. Most of the community uses [erupted volcanic rock]mais ils sont très éloignés de leurs sources profondes. Donc, si vous pouvez aller directement au manteau, c’est la voie à suivre. Le site [rocks in the current study] sont aussi proches qu’on peut l’être”.

Les résultats peuvent également indiquer des endroits dans le monde où l’on pourrait trouver des gisements de minerai – et de fortes concentrations de cuivre, d’argent et d’or.

“On pense que ces dépôts se forment à partir de fluides magmatiques – des fluides qui se sont séparés du magma initial, qui transportent du cuivre et d’autres métaux en solution”, explique Urann. “Le problème a toujours été que ces gisements nécessitent beaucoup d’eau pour se former – plus que ce que l’on obtient avec des magmas contenant 4 % d’eau. Notre étude montre que les magmas super-hydriques sont des candidats de choix pour former des gisements de minerai économiques.”

Référence : “High water content of arc magmas recorded in cumulates from subduction zone lower crust” par B. M. Urann, V. Le Roux, O. Jagoutz, O. Müntener, M. D. Behn et E. J. Chin, 26 mai 2022, Nature Geoscience.

DOI: 10.1038/s41561-022-00947-w

Cette recherche a été soutenue par la National Science Foundation et le Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Ocean Venture Fund.

![La Terre en 2021 : quelques faits saillants d'une autre année sur notre planète [Video]](https://7zine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/La-Terre-en-2021-quelques-faits-saillants-dune-autre-annee-380x250.jpg)