Par

Cotton grass sur les rives de l’Ilerney inférieur, Russie. Crédit : Alfred-Wegener-Institut / Stefan Kruse

La recherche montre que seules des mesures ambitieuses de protection du climat peuvent encore sauver un tiers de la toundra.

Les températures dans l’Arctique augmentent rapidement en raison du réchauffement climatique. En conséquence, la limite des forêts de mélèzes de Sibérie progresse régulièrement vers le nord, supplantant progressivement les vastes étendues de toundra qui abritent un mélange unique de flore et de faune. Des experts de l’Institut Alfred Wegener ont maintenant préparé une simulation informatique de la manière dont ces forêts pourraient s’étendre à l’avenir, au détriment de la toundra. Leur conclusion : seules des mesures cohérentes de protection du climat permettront à environ 30 % de la toundra sibérienne de survivre jusqu’au milieu du millénaire. Dans tous les autres scénarios, moins favorables, cet habitat unique devrait disparaître complètement.

La crise climatique a un impact particulier sur l’Arctique : dans le Grand Nord, la température moyenne de l’air a augmenté de plus de deux degrés Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) over the past 50 years – far more than anywhere else. And this trend will only continue. If ambitious greenhouse-gas reduction measures (Emissions Scenario RCP 2.6) are taken, the further warming of the Arctic through the end of the century could be limited to just below two degrees. According to model-based forecasts, if the emissions remain high (Scenario RCP 8.5), we could see a dramatic rise in the average summer temperatures in the Arctic – by up to 14 degrees Celsius (25 degrees Fahrenheit) over today’s norm by 2100.

Crooked wood images in Keperveem, Russia. Credit: Stefan Kruse

“For the Arctic Ocean and the sea ice, the current and future warming will have serious consequences,” says Prof Ulrike Herzschuh, Head of the Polar Terrestrial Environmental Systems Division at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI). “But the environment on land will also change drastically. The broad expanses of tundra in Siberia and North America will be massively reduced, as the treeline, which is already slowly changing, rapidly advances northward in the near future. In the worst-case scenario, there will be virtually no tundra left by the middle of the millennium. In the course of our study, we simulated this process for the tundra in northeast Russia. The central question that concerned us was: which emissions path does humanity have to follow in order to preserve the tundra as a refuge for flora and fauna, as well its role for the cultures of indigenous peoples and their traditional ties to the environment?”

Crooked wood needle sampling on the Taimyr Peninsula. Credit: Stefan Kruse

The tundra is home to a unique community of plants, roughly five percent of which are endemic, i.e., can only be found in the Arctic. Typical species include the mountain avens, Arctic poppy, and prostrate shrubs like willows and birches, all of which have adapted to the harsh local conditions: brief summers and long, arduous winters. It also offers a home for rare species like reindeer, lemmings, and insects like the Arctic bumblebee.

Aerial photo of open Northern forest on the Taymyr Peninsula, Siberia, (proximity of the river Chatanga) consisting of larches. In some parts of this area, the trees are growing in dense formations, but in others, one can see just very few trees. Credit: Stefan Kruse

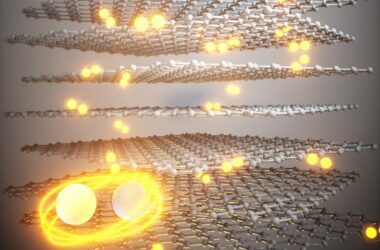

For their simulation, Ulrike Herzschuh and AWI modeller Dr Stefan Kruse employed the AWI vegetation model LAVESI. “What sets LAVESI apart is that it allows us to display the entire treeline at the level of individual trees,” Kruse explains. “The model portrays the entire lifecycle of Siberian larches in the transition zone to the tundra – from seed production and distribution, to germination, to fully grown trees. In this way, we can very realistically depict the advancing treeline in a warming climate.”

Single trees in the tundra near lake Nutenvut in Keperveem, Russia. Credit: Stefan Kruse

The findings speak for themselves: the larch forests could spread northward at a rate of up to 30 kilometers (19 miles) per decade. The tundra expanses, which can’t shift to colder regions due to the adjacent Arctic Ocean, would increasingly dwindle. Since trees aren’t mobile and each one’s seeds can only reach a limited distribution radius, initially the vegetation would significantly lag behind the warming, but then catch up to it again. In the majority of scenarios, by mid-millennium less than six percent of today’s tundra would remain; saving roughly 30 percent would only be possible with the aid of ambitious greenhouse-gas reduction measures. Otherwise, Siberia’s once 4,000-kilometer-long (2,500-mile-long), unbroken tundra belt would shrink to two patches, 2,500 kilometers (1,600 miles) apart, on the Taimyr Peninsula to the west and Chukotka Peninsula to the east. Interestingly, even if the atmosphere cooled again in the course of the millennium, the forests would not completely release the former tundra areas.

Vegetation photos on the slope of the mountain in Keperveem, Russia. Credit: Julius Schröder

“At this point, it’s a matter of life and death for the Siberian tundra,” says Eva Klebelsberg, Project Manager Protected Areas and Climate Change / Russian Arctic at the WWF Germany, with regard to the study. “Larger areas can only be saved with very ambitious climate protection targets. And even then, in the best case, there will ultimately be two discrete refuges, with smaller flora and fauna populations that are highly vulnerable to disrupting influences. That’s why it’s important that we intensify and expand protective measures and protected areas in these regions, so as to preserve refuges for the tundra’s unparalleled biodiversity,” adds Klebelsberg, who, in collaboration with the Alfred Wegener Institute, is an advocate for the establishment of protected areas.

“After all, one thing is clear: if we continue with business as usual, this ecosystem will gradually disappear.”

Reference: “Regional opportunities for tundra conservation in the next 1000 years” by Stefan Kruse and Ulrike Herzschuh, 24 May 2022, eLife.

DOI: 10.7554/eLife.75163

![Explorer la Terre depuis l'espace : Journée de la Terre [Video]](https://7zine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/1650734287_Explorer-la-Terre-depuis-lespace-Journee-de-la-Terre-380x250.jpg)