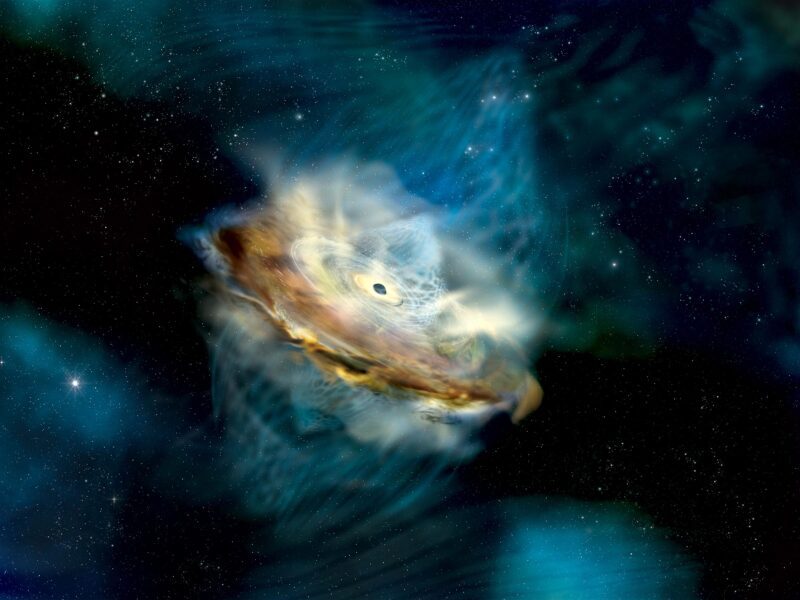

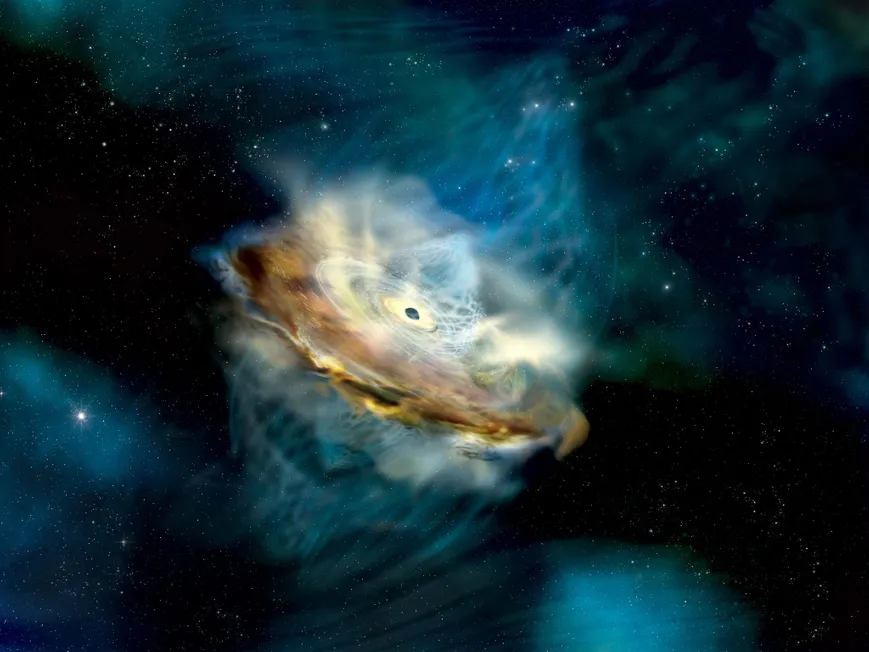

Cette illustration montre le disque d’accrétion, la couronne (tourbillons coniques pâles au-dessus du disque) et le trou noir supermassif de la galaxie active 1ES 1927+654 avant sa récente éruption. Crédit : NASA/Sonoma State University, Aurore Simonnet

Quelque chose de bizarre se passe dans la galaxie connue sous le nom de 1ES 1927+654 : fin 2017, et pour des raisons que les scientifiques n’ont pas pu expliquer, le trou noir supermassif assis au cœur de cette galaxie a subi une crise d’identité massive. En l’espace de quelques mois, l’objet déjà brillant, qui est si lumineux qu’il appartient à une classe de trous noirs connus sous le nom de noyaux actifs de galaxie (NAG), est soudainement devenu beaucoup plus brillant – brillant près de 100 fois plus que la normale en lumière visible.

Une équipe internationale d’astrophysiciens, dont des scientifiques de l’Université du Colorado à Boulder (CU Boulder), a peut-être trouvé la cause de ce changement. Les lignes de champ magnétique qui traversent le black hole appear to have flipped upside down, causing a quick but fleeting change in the object’s properties. It was as if compasses on Earth suddenly began pointing south instead of north.

The findings, published on May 5, 2022, in The Astrophysical Journal, could change how scientists look at supermassive black holes, said study coauthor Nicolas Scepi.

“Normally, we would expect black holes to evolve over millions of years,” said Scepi, a postdoctoral researcher at JILA, a joint research institute between CU Boulder and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). “But these objects, which we call changing-look AGNs, evolve over very short time scales. Their magnetic fields may be key to understanding this rapid evolution.”

Scepi, alongside JILA Fellows Mitchell Begelman and Jason Dexter, first theorized that such a magnetic flip-flop could be possible in 2021.

Explorez l’éruption inhabituelle de 1ES 1927+654, une galaxie située à 236 millions d’années-lumière dans la constellation de Draco. Une inversion soudaine du champ magnétique autour de son trou noir d’un million de masse solaire pourrait avoir déclenché l’éruption. Crédit : ;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

The new study supports the idea. In it, a team led by Sibasish Laha of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center collected the most comprehensive data yet on this far-away object. The group drew on observations from seven telescope arrays on the ground and in space, tracing the flow of radiation from 1ES 1927+654 as the AGN blazed bright then dimmed back down.

The observations suggest that the magnetic fields of supermassive black holes may be a lot more dynamic than scientists once believed. And, Begelman noted, this AGN probably isn’t alone.

“If we saw this in one case, we’ll definitely see it again,” said Begelman, professor in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS). “Now we know what to look for.”

An unusual black hole

Begelman explained that AGNs are borne out of some of the most extreme physics in the known universe.

These monsters arise when supermassive black holes begin to pull in huge amounts of gas from the galaxies around them. Like water circling a drain, that material will spin faster and faster the closer it gets to the black hole—forming a bright “accretion disk” that generates intense and varied radiation that scientists can view from billions of light-years away.

Those accretion disks also give rise to a curious feature: They generate strong magnetic fields that wrap around the central black hole and, like Earth’s own magnetic field, point in a distinct direction, such as north or south.

“There’s increasingly evidence from the Event Horizon Telescope and other observations that magnetic fields might play a key role in influencing how gas falls onto black holes,” said Dexter, assistant professor in APS.

Which could also influence how bright an AGN, like the one at the heart of 1ES 1927+654, looks through telescopes.

By May 2018, this object’s surge in energy had reached a peak, ejecting more visible light but also many times more ultraviolet radiation than usual. Around the same time, the AGN’s emissions of X-ray radiation began to dim.

“Normally, if the ultraviolet rises, your X-rays will also rise,” Scepi said. “But here, the ultraviolet rose, while the X-ray decreased by a lot. That’s very unusual.”

Turning on its head

Researchers at JILA proposed a possible answer for that unusual behavior in a paper published last year.

Begelman explained that these features are constantly pulling in gas from outside space, and some of that gas also carries magnetic fields. If the AGN pulls in magnetic fields that point in an opposite direction to its own—they point south, say, instead north—then its own field will weaken. It’s a bit like how a tug-of-war team tugging on a rope in one direction can nullify the efforts of their opponents pulling the other way.

With this AGN, the JILA team theorized, the black hole’s magnetic field got so weak that it flipped upside down.

“You’re basically wiping out the magnetic field entirely,” Begelman said.

In the new study, researchers led by NASA set out to collect as many observations as they could of 1ES 1927+654.

The disconnect between ultraviolet and X-ray radiation turned out to be the smoking gun. Astrophysicists suspect that a weakening magnetic field would cause just such a change in the physics of an AGN—shifting the black hole’s accretion disk so that it ejected more ultraviolet and visible light and, paradoxically, less X-ray radiation. No other theory could explain what the researchers were seeing.

The AGN itself quieted down and returned to normal by summer 2021. But Scepi and Begelman view the event as a natural experiment—a way of probing close to the black hole to learn more about how these objects fuel bright beams of radiation. That information, in turn, may help scientists know exactly what kinds of signals they should look for to find more weird AGNs in the night sky.

“Maybe there are some similar events that have already been observed—we just don’t know about them yet,” Scepi said.

Reference: “A radio, optical, UV and X-ray view of the enigmatic changing look Active Galactic Nucleus 1ES~1927+654 from its pre- to post-flare states” by Sibasish Laha (NASA-GSFC), Eileen Meyer, Agniva Roychowdhury, Josefa Becerra González, J. A. Acosta-Pulido, Aditya Thapa, Ritesh Ghosh, Ehud Behar, Luigi C. Gallo, Gerard A. Kriss, Francesca Panessa, Stefano Bianchi, Fabio La Franca, Nicolas Scepi, Mitchell C. Begelman, Anna Lia Longinotti, Elisabeta Lusso, Samantha Oates, Matt Nicholl and S. Bradley Cenko, 18 May 2022, The Astrophysical Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ac63aa

arXiv:2203.07446

Other co-authors on the new study included researchers from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County in the U.S.; Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in Spain; Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics in India; Technion in Israel; Space Telescope Science Institute in the U.S.; National Institute for Astrophysics in Italy; Roma Tre University in Italy; National Autonomous University of Mexico; University of Florence in Italy; and the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom.