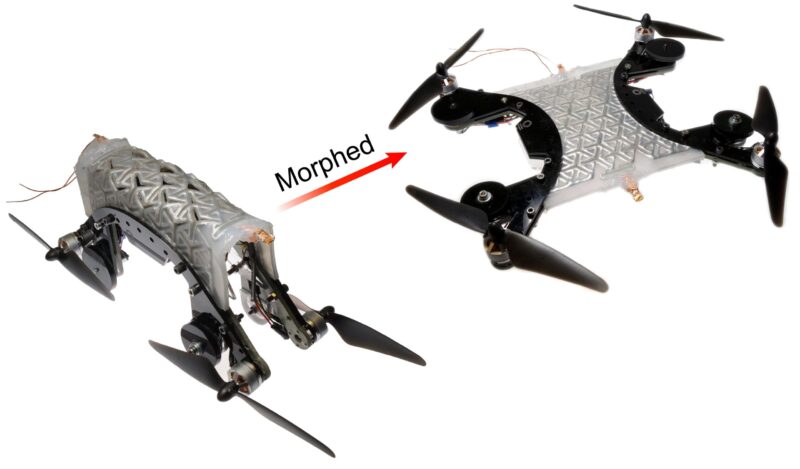

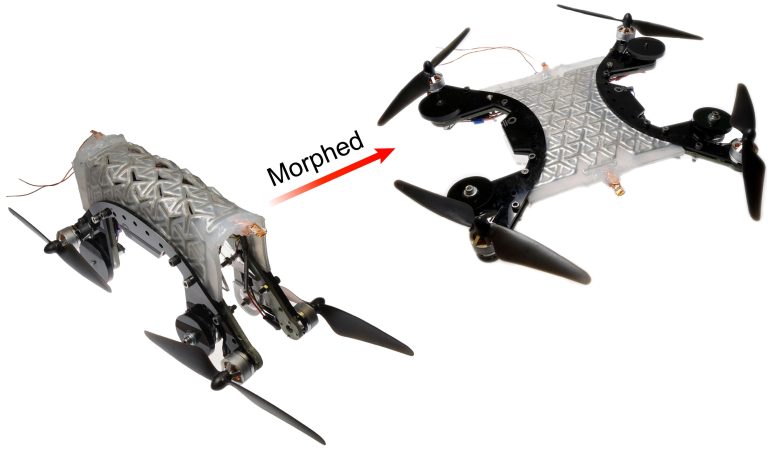

Drone capable de se transformer et de se plier en utilisant du métal liquide. Crédit : Virginia Tech

Imaginez un petit véhicule autonome qui pourrait rouler sur un terrain, s’arrêter et s’aplatir pour devenir un quadcoptère. Les rotors se mettent à tourner et le véhicule s’envole. En l’observant de plus près, que pensez-vous voir ? Quels mécanismes l’ont fait passer d’un véhicule terrestre à un quadcoptère volant ? Vous pourriez imaginer des engrenages et des courroies, peut-être une série de minuscules servomoteurs qui ont mis toutes ses pièces en place.

Si ce mécanisme était conçu par une équipe de Virginia Tech dirigée par Michael Bartlett, professeur adjoint en génie mécanique, vous verriez une nouvelle approche de la modification des formes au niveau des matériaux. Ces chercheurs utilisent le caoutchouc, le métal et la température pour modeler les matériaux et les fixer en place, sans moteur ni poulie. Les travaux de l’équipe ont été publiés dans Science Robotics. Les coauteurs de l’article sont les étudiants diplômés Dohgyu Hwang et Edward J. Barron III et le chercheur postdoctoral A. B. M. Tahidul Haque.

Se mettre en forme

La nature est riche en organismes qui changent de forme pour remplir différentes fonctions. La pieuvre se transforme radicalement pour se déplacer, manger et interagir avec son environnement ; les humains fléchissent leurs muscles pour supporter des charges et garder leur forme ; et les plantes se déplacent pour capter la lumière du soleil tout au long de la journée. Comment créer un matériau qui remplit ces fonctions pour permettre la création de nouveaux types de robots multifonctionnels et morphing ?

“Lorsque nous avons lancé le projet, nous voulions un matériau capable de faire trois choses : changer de forme, conserver cette forme et revenir à la configuration d’origine, et ce, sur de nombreux cycles”, explique M. Bartlett. “L’un des défis était de créer un matériau suffisamment souple pour changer radicalement de forme, mais suffisamment rigide pour créer des machines adaptables pouvant remplir différentes fonctions.”

Pour créer une structure pouvant être transformée, l’équipe s’est tournée vers le kirigami, l’art japonais consistant à créer des formes en papier par découpe. (Cette méthode diffère de l’origami, qui utilise le pliage.) En observant la résistance de ces motifs kirigami dans les caoutchoucs et les composites, l’équipe a pu créer une architecture matérielle constituée d’un motif géométrique répétitif.

Edward Barron, Michael Bartlett et Dohgyu Hwang tiennent un morceau de matériau qui a été déformé. Crédit : Photo d’Alex Parrish pour Virginia Tech

Ils avaient ensuite besoin d’un matériau capable de conserver sa forme tout en permettant de l’effacer à la demande. C’est là qu’ils ont introduit un endosquelette fait d’un alloy (LMPA) embedded inside a rubber skin. Normally, when a metal is stretched too far, the metal becomes permanently bent, cracked, or stretched into a fixed, unusable shape. However, with this special metal embedded in rubber, the researchers turned this typical failure mechanism into a strength. When stretched, this composite would now hold a desired shape rapidly, perfect for soft morphing materials that can become instantly load bearing.

Finally, the material had to return the structure back to its original shape. Here, the team incorporated soft, tendril-like heaters next to the LMPA mesh. The heaters cause the metal to be converted to a liquid at 60 degrees Celsius (140 degrees Fahrenheit), or 10 percent of the melting temperature of aluminum. The elastomer skin keeps the melted metal contained and in place, and then pulls the material back into the original shape, reversing the stretching, giving the composite what the researchers call “reversible plasticity.” After the metal cools, it again contributes to holding the structure’s shape.

“These composites have a metal endoskeleton embedded into a rubber with soft heaters, where the kirigami-inspired cuts define an array of metal beams. These cuts combined with the unique properties of the materials were really important to morph, fix into shape rapidly, then return to the original shape,” Hwang said.

The researchers found that this kirigami-inspired composite design could create complex shapes, from cylinders to balls to the bumpy shape of the bottom of a pepper. Shape change could also be achieved quickly: After impact with a ball, the shape changed and fixed into place in less than 1/10 of a second. Also, if the material broke, it could be healed multiple times by melting and reforming the metal endoskeleton.

One drone for land and air, one for sea

The applications for this technology are only starting to unfold. By combining this material with onboard power, control, and motors, the team created a functional drone that autonomously morphs from a ground to air vehicle. The team also created a small, deployable submarine, using the morphing and returning of the material to retrieve objects from an aquarium by scraping the belly of the sub along the bottom.

“We’re excited about the opportunities this material presents for multifunctional robots. These composites are strong enough to withstand the forces from motors or propulsion systems, yet can readily shape morph, which allows machines to adapt to their environment,” said Barron.

Looking forward, the researchers envision the morphing composites playing a role in the emerging field of soft robotics to create machines that can perform diverse functions, self-heal after being damaged to increase resilience, and spur different ideas in human-machine interfaces and wearable devices.

Reference: “Shape morphing mechanical metamaterials through reversible plasticity” by Dohgyu Hwang, Edward J. Barron III, A. B. M. Tahidul Haque and Michael D. Bartlett, 9 February 2022, Science Robotics.

DOI: 10.1126/scirobotics.abg2171

This project was funded through Bartlett’s DARPA Young Faculty Award and Director’s Fellowship.