Grâce au télescope SOAR (Southern Astrophysical Research) de 4,1 mètres situé sur le Cerro Pachón au Chili, les astronomes ont confirmé qu’un astéroïde découvert en 2020 par l’étude Pan-STARRS1, appelé 2020 XL5, est un troyen terrestre (un compagnon de la Terre qui suit la même trajectoire autour du Soleil que la Terre) et ont révélé qu’il est beaucoup plus grand que le seul autre troyen terrestre connu. Sur cette illustration, l’astéroïde est représenté au premier plan, en bas à gauche. Les deux points lumineux au-dessus de lui, à l’extrême gauche, sont la Terre (à droite) et la Lune (à gauche). Le Soleil apparaît à droite. Crédit : NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva/Spaceengine, Remerciements : M. Zamani (NOIRLab de la NSF)

Une équipe internationale d’astronomes dirigée par le chercheur Toni Santana-Ros, de l’Université d’Alicante et de l’Institut des Sciences du Cosmos de l’Université de Barcelone (ICCUB), a confirmé l’existence du deuxième astéroïde troyen terrestre connu à ce jour, le 2020 XL.5après une décennie de recherches. Les résultats de l’étude ont été publiés dans la revue Nature Communications.

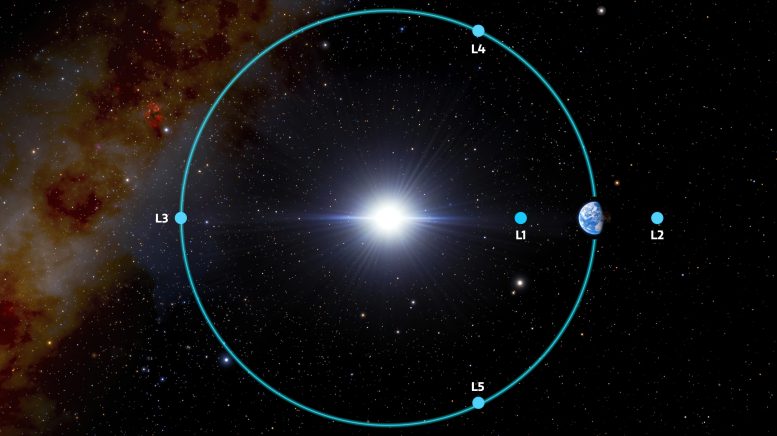

Tous les objets célestes qui errent dans notre système solaire ressentent l’influence gravitationnelle de tous les autres corps massifs qui le composent, y compris le Soleil et les planètes. Si l’on considère uniquement le système Terre-Soleil, les lois de la gravité de Newton stipulent qu’il existe cinq points où toutes les forces qui agissent sur un objet situé en ce point s’annulent. Ces régions sont appelées points de Lagrange, et ce sont des zones de grande stabilité. Terre Les astéroïdes troyens sont de petits corps qui orbitent autour de la L4 ou L5 Points de Lagrange du système Soleil-Terre.

Ces résultats confirment que 2020 XL5 est le deuxième astéroïde troyen terrestre transitoire connu à ce jour, et tout indique qu’il restera troyen -c’est-à-dire qu’il sera situé au point de Lagrange- pendant quatre mille ans, il est donc qualifié de transitoire. Les chercheurs ont fourni une estimation de la taille globale de l’objet (environ un kilomètre de diamètre, plus grande que celle de l’astéroïde troyen terrestre connu à ce jour, le 2010 TK7qui avait un diamètre de 0,3 kilomètre), et ont étudié l’impulsion nécessaire à une fusée pour atteindre l’astéroïde depuis la Terre.

Les points de Lagrange sont des endroits dans l’espace où les forces gravitationnelles de deux corps massifs, tels que le Soleil et une planète, s’équilibrent, ce qui facilite la mise en orbite d’un objet de faible masse (tel qu’un vaisseau spatial ou un astéroïde). Ce diagramme montre les cinq points de Lagrange pour le système Terre-Soleil. (La taille de la Terre et les distances dans l’illustration ne sont pas à l’échelle.) Crédit : NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva, Remerciements : M. Zamani (NOIRLab de la NSF)

Bien que l’on sache depuis des décennies qu’il existe des astéroïdes troyens sur d’autres planètes, comme Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune, it was not until 2011 that the first Earth Trojan asteroid was found. The astronomers have described many observational strategies for the detection of new Earth Trojans. “There have been many previous attempts to find Earth Trojans, including in situ surveys such as the search within the L4 region, carried out by the NASA OSIRIS-Rex spacecraft, or the search within the L5 region, conducted by the JAXA Hayabusa-2 mission,” notes Toni Santana-Ros, author of the publication. He adds that “all the dedicated efforts had so far failed to discover any new member of this population.”

The low success in these searches can be explained by the geometry of an object orbiting the Earth-Sun L4 or L5 as seen from our planet. These objects are usually observable close to the sun. The observation time window between the asteroid rising above the horizon and sunrise is, therefore, very small. Therefore, astronomers point their telescopes very low on the sky where the visibility conditions are at their worst and with the handicap of the imminent sunlight saturating the background light of the images just a few minutes in the observation.

To solve this problem, the team carried out a search of 4-meter telescopes that would be able to observe under such conditions, and they finally obtained the data from the 4.3m Lowel Discovery telescope (Arizona, United States), and the 4.1m SOAR telescope, operated by the National Science Foundation NOIRLab (Cerro Pachón, Chile).

The discovery of the Earth Trojan asteroids is very significant because these can hold a pristine record on the early conditions in the formation of the Solar System, since the primitive trojans might have been co-orbiting the planets during their formation, and they add restrictions to the dynamic evolution of the Solar System. In addition, Earth Trojans are the ideal candidates for potential space missions in the future.

Since the L4 Lagrangian point shares the same orbit as the Earth, it takes a low change in velocity to be reached. This implies that a spacecraft would need a low energy budget to remain in its shared orbit with the Earth, keeping a fixed distance to it. “Earth Trojans could become ideal bases for an advanced exploration of the Solar System; they could even become a source of resources,” concludes Santana-Ros.

The discovery of more trojans will enhance our knowledge of the dynamics of these unknown objects and will provide a better understanding of the mechanics that allow them to be transient.

For more on this research, see Existence of Earth Trojan Asteroid Confirmed.

Reference: “Orbital stability analysis and photometric characterization of the second Earth Trojan asteroid 2020 XL5” by T. Santana-Ros, M. Micheli, L. Faggioli, R. Cennamo, M. Devogèle, A. Alvarez-Candal, D. Oszkiewicz, O. Ramírez, P.-Y. Liu, P. G. Benavidez, A. Campo Bagatin, E. J. Christensen, R. J. Wainscoat, R. Weryk, L. Fraga, C. Briceño and L. Conversi, 1 February 2022, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-27988-4