L’incendie Woolsey de 2018 en Californie a brûlé près de 100 000 acres dans les comtés de Los Angeles et de Ventura. Cette image a été prise le 9 novembre 2018. Crédit : Service des forêts, USDA (avec l’aimable autorisation de Peter Buschmann).

Des scientifiques ont analysé la qualité des eaux côtières dans les mois qui ont suivi un important incendie de forêt en Californie du Sud. Leurs résultats ont été révélateurs.

L’incendie Woolsey de novembre 2018 dans les comtés de Los Angeles et de Ventura en Californie du Sud a laissé derrière lui plus qu’une cicatrice de brûlure de près de 100 000 acres : Il a également laissé les eaux côtières adjacentes avec des niveaux inhabituellement élevés de bactéries fécales et de sédiments qui sont restés pendant des mois.

Pour une nouvelle étude, publiée dans le journal Scientific Reportsles scientifiques ont combiné des images satellites, des données sur les précipitations et des rapports sur la qualité de l’eau pour évaluer deux paramètres standard de la qualité des eaux côtières après l’incendie : la présence de bactéries fécales indicatrices et la turbidité de l’eau.

Les bactéries fécales indicatrices proviennent du tractus gastro-intestinal des humains et d’autres animaux à sang chaud. Bien qu’elles ne soient pas nocives, elles indiquent la présence d’autres bactéries et agents pathogènes présents dans les matières fécales qui peuvent l’être. La turbidité a d’autres implications : Dans une eau trouble, la lumière du soleil atteint moins la vie marine – comme le varech et le phytoplancton – qui en dépend pour survivre.

Lorsqu’il pleut, les eaux de ruissellement transportent généralement des bactéries et des sédiments de la terre vers les eaux côtières. Mais l’énorme pic de ces deux éléments après l’incendie était tout sauf typique.

La cicatrice de l’incendie de Woolsey, représentée en rouge, était suffisamment grande pour être visible depuis l’espace, comme le montre cette vue du satellite Terra de la NASA. Les couleurs de l’image ont été améliorées pour simuler une apparence plus naturelle. Crédit : Observatoire de la Terre de la NASA

“Après l’incendie, nous avons constaté des changements radicaux dans la qualité de l’eau, en particulier sur les plages qui drainent la zone brûlée”, a déclaré l’auteur principal de l’étude, Marisol Cira, candidate au doctorat à l’UCLA et stagiaire au . et stagiaire à ;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “In those areas, both total coliform bacteria and enterococcus were far greater than pre-fire levels, as was turbidity plume size.”

More specifically, the researchers concluded that the post-fire monthly average of total coliforms – a large group of fecal indicator bacteria that can be found in soil, on plants, and in human waste – was 10 times higher than it was for any month in the previous 12 years’ worth of data. Enterococcus, which indicates the presence of bacteria that can cause gastrointestinal disease, was 53 times higher – and well above what is considered safe for recreational use of the water. (Local authorities issued water quality warnings at the time.)

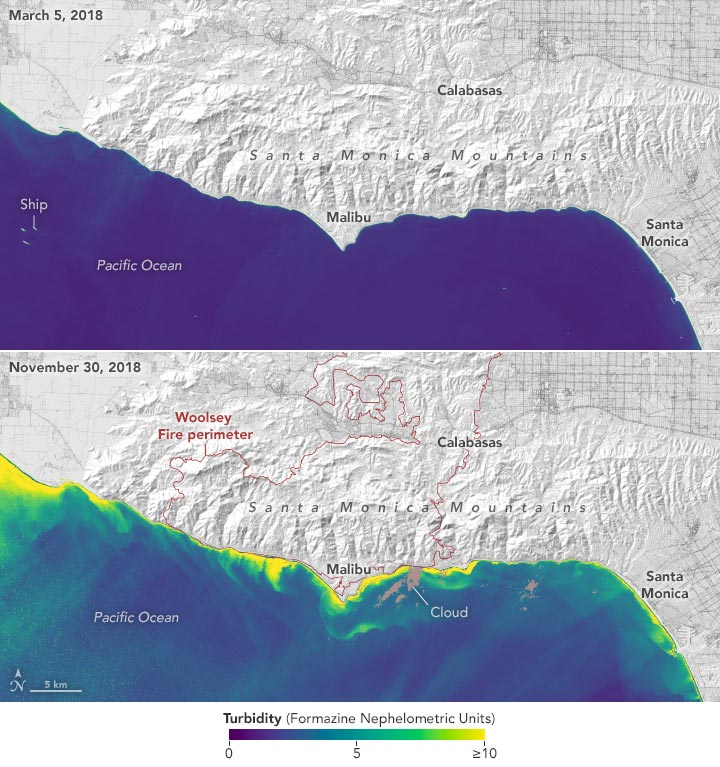

The Woolsey Fire led to a spike in turbidity, or cloudiness from sediment, in coastal waters off Southern California. This annotated map shows turbidity before (top) and after the fire, with bright yellow indicating the largest increases. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

To assess turbidity levels, the study team analyzed satellite imagery from before, during, and after the fire. They were able to estimate the size of sediment plumes that moved into coastal waters following rain events – when turbidity levels usually increase. They found that the surface areas of turbidity plumes during the first storm following the Woolsey Fire were about 10 times greater than those following similar rain events from pre-fire years.

Researchers noted that bacteria levels remained high through February 2019 and took six months to return to pre-fire levels; turbidity remained high for three months before returning to previous levels.

Why the Fire Is Responsible

During normal conditions, soil absorbs much of the water that falls when it rains, preventing a lot of bacteria and sediment from making its way to the coast. But after a fire, that’s not the case.

“When a fire burns through a forest, it increases the amount of vegetation litter on the ground and changes the chemistry of the soils in a way that makes them unable to absorb water,” said Christine Lee, a study coauthor at JPL. “So rather than getting absorbed into the soil, rain runs off into local water bodies and coastal systems, carrying sediment and bacteria with it.”

The researchers also looked at the amount of post-fire fecal indicator bacteria in the water during different weather conditions. They found that more bacteria were present in wet weather than in dry weather; but, in both cases, average monthly bacteria levels showed dramatic and prolonged increases over pre-fire levels.

“Usually when there’s a spike of bacteria in the water, it only lasts a day or two,” said Luke Ginger, scientist and study coauthor from the nonprofit Heal the Bay in Santa Monica, California. “But after the fire, there were months of sustained high bacteria. So that was a big concern.”

What’s Next

Wildfire seasons are becoming longer and more intense; in fact, the seven largest California wildfires on record have occurred during the last four years.

“Climate change will likely exacerbate the effects we see here in terms of water quality as wildfire and rainfall patterns continue to change,” said Ginger. “A key part in protecting our ecosystems and communities is understanding these emerging threats and spreading awareness about them.”

While this study examined only the effects of the 2018 Woolsey Fire, an upcoming NASA project called KelpFire, funded by NASA’s Minority University Research and Education Program (MUREP), will explore additional coastal watersheds in California. This effort will dive deeper into how fire-related impacts like those discussed in this study affect the greater coastal ecosystem, such as kelp forests.

Reference: “Turbidity and fecal indicator bacteria in recreational marine waters increase following the 2018 Woolsey Fire” by Marisol Cira, Anisha Bafna, Christine M. Lee, Yuwei Kong, Benjamin Holt, Luke Ginger, Kerry Cawse-Nicholson, Lucy Rieves and Jennifer A. Jay, 14 February 2022, Scientific Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-05945-x