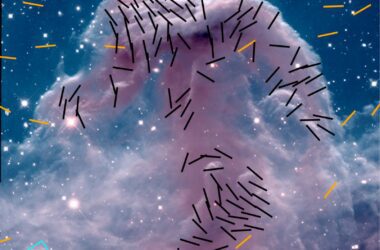

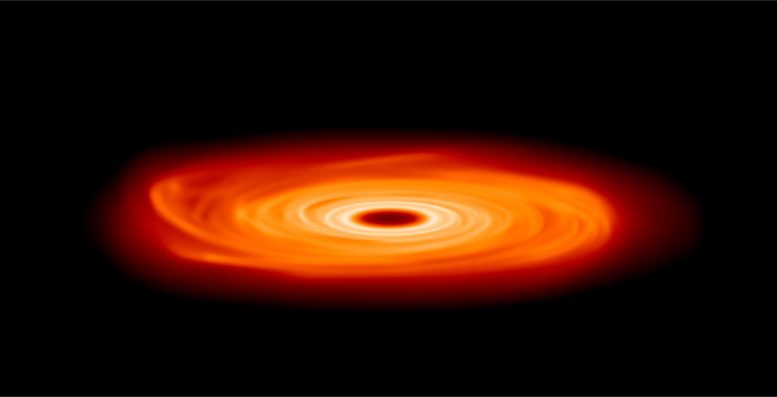

L’impact d’une distorsion qui efface la structure spirale d’un disque protoplanétaire. Crédit : Université de Warwick

Une nouvelle étude de l’University of Warwick demonstrates the impact of passing stars, misaligned binary stars, and passing gas clouds on the formation of planets in early star systems.

- University of Warwick scientists identify a process that hinders the formation of planets through Gravitational Instability in the early evolution of solar systems

- Protoplanetary discs have been observed by astronomers with warps curving their surface

- Modeling from the Warwick team demonstrates that these warps can wipe out the spiral structure that allows planets to form via Gravitational Instability

Image showing a rotating protoplanetary disc without a warp. Credit: University of Warwick

A new study from the University of Warwick demonstrates the impact of passing stars, misaligned binary stars, and passing gas clouds on the formation of planets in early star systems.

Scientists have modeled how cosmic events like these can warp protoplanetary discs, the birthplaces of planets, in the early evolution of solar systems. Their results were published on February 3, 2022, in the Astrophysical Journal in a study funded by The Royal Society and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, part of UK Research and Innovation.

Solar systems are formed from protoplanetary discs, massive spinning clouds of gas and dust that will eventually coalesce into the array of planets that we see in the Universe. When these discs are young they form spiral structures, with all their dust and material dragged into dense arms by the massive gravitational effect of the disc spinning.

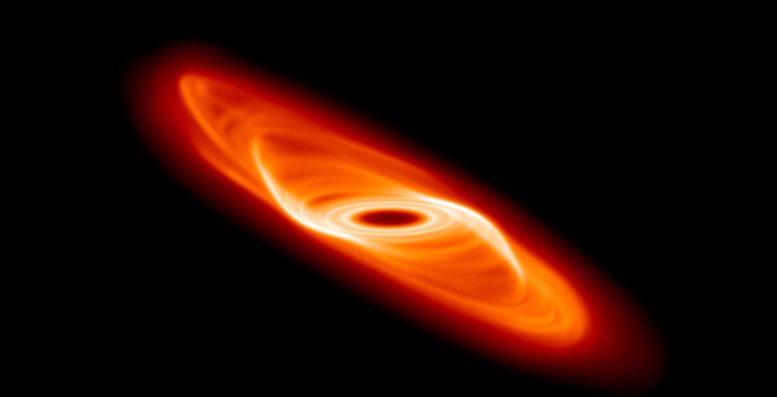

Image showing a rotating protoplanetary disc with a warp in its initial stages. Credit: University of Warwick

But astronomers have found a surprising number of protoplanetary discs that, despite being massive enough to have a spiral structure, show no evidence of one. The University of Warwick team have been investigating what might prevent a disc from forming a spiral structure.

PhD student Sahl Rowther from the University’s Department of Physics created a three-dimensional hydrodynamical simulation of a normal, flat self-gravitating disc using a technique called smoothed-particle hydrodynamics. To this, he added different levels of curvature to the disc to warp it, to study the impact on the disc’s spiral structure. In all but the smallest warps, the spiral structure disappeared.

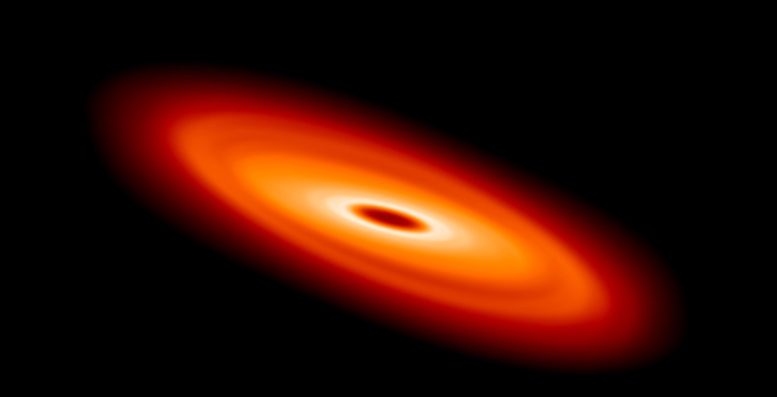

Image showing a rotating protoplanetary disc with a warp in later stages. Credit: University of Warwick

The spiral structure in a protoplanetary disc is vital for the formation of planets through Gravitational Instability and the results improve our understanding of how solar systems evolve.

Co-author Dr. Rebecca Nealon, Stephen Hawking Fellow in the Department of Physics, said: “Warps will inhibit planet formation through Gravitational Instability, in the sense that these spiral structures, which fragment into clumps that eventually form planets, are where the disc structure will be disrupted. Anything that disturbs that spiral structure makes it harder for that clumping to occur and harder for the planets to form via Gravitational Instability.”

The scientists explain that the warp heats up the disc by inducing small perturbations to the velocity of the gas as it orbits. The gas needs to be cool in order to clump together, so in heating up the disc the spiral arm structure is wiped out.

There are a number of ways that a protoplanetary disc can be warped. A few examples include; if a large object, such as a star, passes nearby in a flyby encounter; if the disc surrounds a binary star system that orbits out of alignment with the disc; or if a nearby source of gas accretes onto the disc.

Vidéo montrant l’impact d’une distorsion lorsqu’elle efface la structure spirale d’un disque protoplanétaire. Crédit : Université de Warwick

Ces dernières années, les preuves de la présence de disques protoplanétaires déformés ont augmenté de manière significative, ce qui suggère qu’ils sont plus courants dans l’Univers qu’on ne le pensait auparavant. Cela fournit également une explication potentielle pour le grand nombre de disques protoplanétaires massifs qui ne présentent pas de structure spirale.

Le Dr Nealon ajoute : “Normalement, nous pensons que ces disques se forment de manière isolée, mais ce n’est pas vraiment le cas. Il s’agit d’un voisinage chaotique, avec beaucoup d’étoiles à proximité, et il se peut qu’une étoile passe à proximité et que l’interaction gravitationnelle soit suffisante pour provoquer cette déformation.

“Une fois que nous avons commencé à observer des disques déformés, nous avons dû commencer à prendre en compte les déformations dans notre modélisation. Nous devons mieux prendre en compte les distorsions dans l’évolution des disques protoplanétaires et comprendre que les distorsions peuvent avoir un impact sur les mécanismes et la physique de l’évolution des disques existants. Nous devons considérer comment les distorsions affectent tous les facteurs de la formation planétaire.”

Sahl Rowther a déclaré : “Cette étude combine deux effets physiques qui n’ont pas été combinés auparavant, la physique des disques autogravitants avec la distorsion. C’est important car les disques autogravitants ont été étudiés pendant un certain temps et c’est un domaine bien établi. Les distorsions sont une idée beaucoup plus récente.

“Nous avons modélisé cela de la manière la plus simple possible pour nous permettre d’être vraiment sûrs de ce que nous avons fait, et de le démontrer facilement.”

Référence : “Warping Away Gravitational Instabilities in Protoplanetary Discs” par Sahl Rowther, Rebecca Nealon et Farzana Meru, 3 février 2022, The Astrophysical Journal.

DOI : 10.3847/1538-4357/ac3975