Un écart d’une seconde dans le temps de parcours d’une série d’ondes sismiques nous donne un aperçu important et sans précédent de ce qui se passe à l’intérieur de la Terre.

La théorie sous-tend notre compréhension de la convection dans le noyau externe de la Terre et de sa fonction dans le contrôle du champ magnétique de la planète. Les scientifiques n’ont jamais observé directement les flux convectifs ou leur évolution. Le géoscientifique de Virginia Tech, Ying Zhou, en apporte la preuve pour la première fois.

Un grand tremblement de terre a secoué la région des îles Kermadec dans l’océan Pacifique Sud en mai 1997. Un peu plus de 20 ans plus tard, en septembre 2018, un deuxième gros tremblement de terre a frappé le même endroit, avec ses vagues d’énergie sismique émanant de la même région.

Bien que deux décennies séparent les tremblements de terre, comme ils se sont produits dans la même région, on s’attendrait à ce qu’ils envoient des ondes sismiques à travers les couches de la Terre à la même vitesse, a déclaré Ying Zhou, un géoscientifique du département des géosciences du Virginia Tech College of Science.

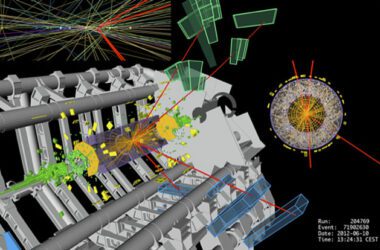

La trajectoire bleue illustre une onde sismique pénétrant dans le noyau terrestre et traversant une région du noyau externe, où la vitesse sismique a augmenté parce qu’un flux de faible densité s’est déplacé dans la région. Crédit : Ying Zhou de Virginia Tech

Cependant, dans les données enregistrées dans quatre des plus de 150 stations du Réseau sismographique mondial qui enregistrent les vibrations sismiques en temps réel, Zhou a trouvé une anomalie surprenante parmi les événements jumeaux. Lors du séisme de 2018, un ensemble d’ondes sismiques appelées ondes SKS se sont déplacées environ une seconde plus vite que leurs homologues en 1997.

Selon Zhou, dont les résultats ont été publiés récemment dans la revue Nature Communications Earth & Environment, that one-second discrepancy in SKS wave travel time gives us an important and unprecedented glimpse of what’s happening deeper in the Earth’s interior, in its outer core.

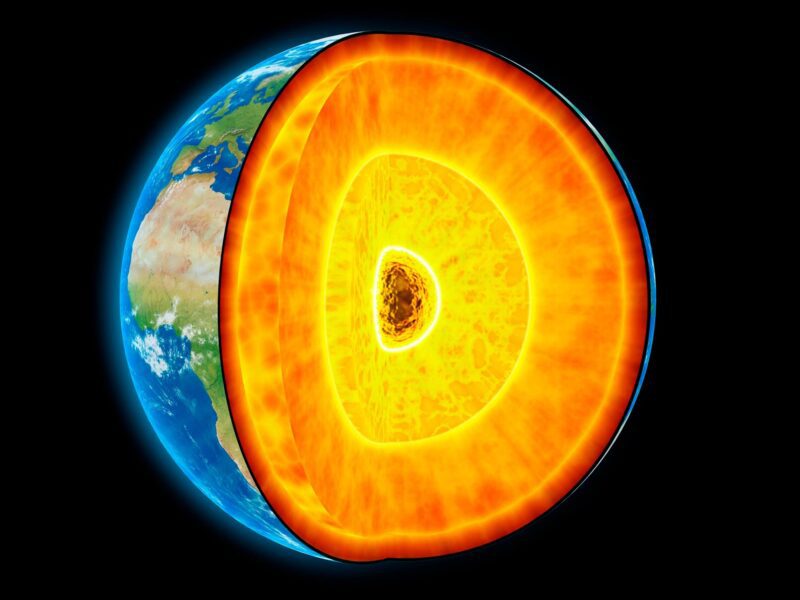

What’s inside counts

Earth’s outer core is sandwiched between the mantle, the thick layer of rock underneath the crust, and the inner core, the planet’s deepest interior layer. It’s mostly made up of liquid iron that undergoes convection, or fluid flow, as the Earth cools. This resulting swirling of liquid metal produces electrical currents responsible for generating the Earth’s magnetic field, called the magnetosphere, which protects the planet and all life on it from harmful radiation and solar winds.

Without its magnetosphere, the Earth could not sustain life, and without the moving flows of liquid metal in the outer core, the magnetic field wouldn’t work. But scientific understanding of this dynamic is based on simulations, said Zhou, an associate professor. “We only know that in theory, if you have convection in the outer core, you’ll be able to generate the magnetic field,” she said.

Blue lines are seismic rays in the outer core, where core-penetrating seismic waves moved through that region faster in 2018 than in 1997. Credit: Image courtesy of Ying Zhou

Scientists also have only been able to speculate about the source of gradual changes in strength and direction of the magnetic field that have been observed, which likely involves changing flows in the outer core.

“If you look at the north geomagnetic pole, it’s currently moving at a speed of about 50 kilometers (31 miles) per year,” Zhou said. “It’s moving away from Canada and toward Siberia. The magnetic field is not the same every day. It’s changing. Since it’s changing, we also speculate that convection in the outer core is changing with time, but there’s no direct evidence. We’ve never seen it.”

Zhou set out to find that evidence. The changes happening in the outer core aren’t dramatic, she said, but they’re worth confirming and fundamentally understanding. In seismic waves and their changes in speed on a decade time scale, Zhou saw a means for “direct sampling” of the outer core. That’s because the SKS waves she studied pass right through it.

“SKS” represents three phases of the wave: First it goes through the mantle as an S wave, or shear wave; then into the outer core as a compressional wave; then back out through the mantle as an S wave. How fast these waves travel depend in part on the density of the outer core that’s in their path. If the density is lower in a region of the outer core as the wave penetrates it, the wave will travel faster, just as the anomalous SKS waves did in 2018.

“Something has changed along the path of that wave, so it can go faster now,” Zhou said.

Ying Zhou of the Virginia Tech Department of Geosciences. Credit: Photo courtesy of Ying Zhou

To Zhou, the difference in wave speed points to low-density regions forming in the outer core in the 20 years since the 1997 earthquake. That higher SKS wave speed during the 2018 earthquake can be attributed to the release of light elements such as hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen in the outer core during convection that takes place as the Earth cools, she said.

“The material that was there 20 years ago is no longer there,” Zhou said. “This is new material, and it’s lighter. These light elements will move upward and change the density in the region where they’re located.”

To Zhou, it’s evidence that movement really is happening in the core, and it’s changing over time, as scientists have theorized. “We’re able to see it now,” she said. “If we’re able to see it from seismic waves, in the future, we could set up seismic stations and monitor that flow.”

What’s next

That’s Zhou’s next effort. Using a method of wave measurement known as interferometry, her team plans to analyze continuous seismic recordings from two seismic stations, one of which will serve as a “virtual” earthquake source, she said.

“We can use earthquakes, but the limitation of relying on earthquake data is that we can’t really control the locations of the earthquakes,” Zhou said. “But we can control the locations of seismic stations. We can put the stations anywhere we want them to be, with the wave path from one station to the other station going through the outer core. If we monitor that over time, then we can see how core-penetrating seismic waves between those two stations change. With that, we will be better able to see the movement of fluid in the outer core with time.”

Reference: “Transient variation in seismic wave speed points to fast fluid movement in the Earth’s outer core” by Ying Zhou, 25 April 2022, Communications Earth & Environment.

DOI: 10.1038/s43247-022-00432-7