Par

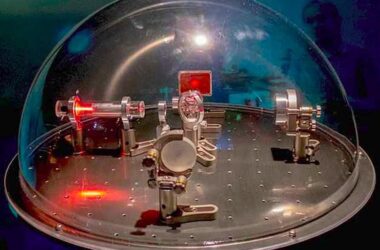

Animation d’une étoile à neutrons en rotation dans l’espace. Les étoiles à neutrons sont directement observables, généralement sous la forme de “pulsars” – les phares du cosmos. Crédit : Laboratoire d’images conceptuelles du Goddard Space Flight Center de la NASA.

Les astronomes ont utilisé gravitational waves to detect merging black holes for years now, but may have to rely on pulsars – rapidly spinning neutron stars – to observe the mergers of supermassive black holes.

When black holes merge, they release enormous amounts of energy in the form of ripples in the fabric of spacetime. These ripples are constantly washing over the Earth, and it’s only through the use of extremely – and I mean extremely – sensitive detectors that we can spot them.

Right now, our gravitational wave detectors are only sensitive to brief, intense pulses, signaling the mergers of relatively small black holes and neutron stars. When giant black holes merge, however, the process takes so long – and produces gravitational waves of such low frequency – that we can’t spot it in the data.

A recent study led by Dr. Boris Goncharov and Prof Ryan Shannon – both researchers from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav) in Australia – are trying a different tactic: instead of observing gravitational waves directly, they’re hoping that pulsars do the hard work for us.

Les pulsars sont une type particulier de neutrons Les pulsars sont un type particulier d’étoiles à neutrons qui tournent rapidement, envoyant un jet de rayonnement sur la Terre à des intervalles de temps précis. Leurs travaux utilisent le Parkes Pulsar Timing Array pour surveiller autant de pulsars que possible. Comme les ondes gravitationnelles d’un black hole merger wiggle through the galaxy, they will cause variations in the timing of the pulses.

Recently, the team announced that they did indeed observe variations in the timings of pulsar flashes, and that the variations are consistent with expectations from gravitational waves. However, they haven’t observed enough pulsars yet to determine if it’s truly a global signal, or just an artifact of their observations.

According to Dr. Goncharov: “To find out if the observed ‘common’ drift has a gravitational wave origin, or if the gravitational-wave signal is deeper in the noise, we must continue working with new data from a growing number of pulsar timing arrays across the world.”

Originally published on Universe Today.

For more on this research, see Pulsar Timing Array Explores Mystery Gravitational Waves From Supermassive Black Holes.