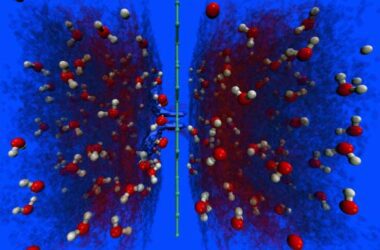

Un navire de recherche en Antarctique le 3 juin 2017, le premier jour où les chercheurs ont vu le soleil se lever au-dessus de l’horizon après des semaines d’obscurité polaire. De nouvelles recherches montrent que le rayonnement solaire est à l’origine du retrait annuel relativement rapide de la glace de mer autour de l’Antarctique à la fin de chaque année civile. Crédit : Ben Adkison

Dans l’hémisphère sud, la couverture de glace autour de l’Antarctique s’étend progressivement de mars à octobre chaque année. Pendant cette période, la superficie totale de la glace est multipliée par 6 pour devenir plus grande que la Russie. La glace de mer se retire ensuite à un rythme plus rapide, de façon plus spectaculaire vers décembre, lorsque l’Antarctique connaît une lumière du jour constante.

De nouvelles recherches menées par le University of Washington explains why the ice retreats so quickly: Unlike other aspects of its behavior, Antarctic sea ice is just following simple rules of physics.

The study was published on March 28, 2022, in Nature Geoscience.

“In spite of the puzzling longer-term trends and the large year-to-year variations in Antarctic sea ice, the seasonal cycle is really consistent, always showing this fast retreat relative to slow growth,” said lead author Lettie Roach, who conducted the study as a postdoctoral researcher at the UW and is now research scientist at NASA and Columbia University. “Given how complex our climate system is, I was surprised that the rapid seasonal retreat of Antarctic sea ice could be explained with such a simple mechanism.”

Previous studies explored whether wind patterns or warm ocean waters might be responsible for the asymmetry in Antarctica’s seasonal sea ice cycle. But the new study shows that, just like a hot summer day reaches its maximum sizzling conditions in late afternoon, an Antarctic summer hits peak melting power in midsummer, accelerating warming and sea ice loss, with slower changes in temperature and sea ice when solar input is low during the rest of the year.

The researchers investigated global climate models and found they reproduced the quicker retreat of Antarctic sea ice. They then built a simple physics-based model to show that the reason is the seasonal pattern of incoming solar radiation.

At the North Pole, Arctic ice cover has gradually decreased since the 1970s with global warming. Antarctic ice cover, however, has seesawed over recent decades. Researchers are still working to understand sea ice around the South Pole and better represent it in climate models.

“I think because we usually expect Antarctic sea ice to be puzzling, previous studies assumed that the rapid seasonal retreat of Antarctic sea ice was also unexpected — in contrast to the Arctic, where the seasons of ice advance and retreat are more similar,” Roach said. “Our results show that the seasonal cycle in Antarctic sea ice can be explained using very simple physics. In terms of the seasonal cycle, Antarctic sea ice is behaving as we should expect, and it is the Arctic seasonal cycle that is more mysterious.”

The researchers are now exploring why Arctic sea ice doesn’t follow this pattern, instead each year growing slightly faster over the Arctic Ocean than it retreats. Because Antarctica’s geography is simple, with a polar continent surrounded by ocean, this aspect of its sea ice may be more straightforward, Roach said.

“We know the Southern Ocean plays an important role in Earth’s climate. Being able to explain this key feature of Antarctic sea ice that standard textbooks have had wrong, and showing that the models are reproducing it correctly, is a step toward understanding this system and predicting future changes,” said co-author Cecilia Bitz, a UW professor of atmospheric sciences.

Reference: “Asymmetry in the seasonal cycle of Antarctic sea ice driven by insolation” by L. A. Roach, I. Eisenman, T. J. W. Wagner, E. Blanchard-Wrigglesworth and C. M. Bitz, 28 March 2022, Nature Geoscience.

DOI: 10.1038/s41561-022-00913-6

Other co-authors are; Edward Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, a UW research assistant professor in atmospheric sciences; Ian Eisenman at Scripps Institution of Oceanography; and Till Wagner at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Roach is currently a research scientist with the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. This work was funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the U.K.-based Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research.