Ground Truth – 2019

GEDI & ; Prévision Sentinel-2 – 2019

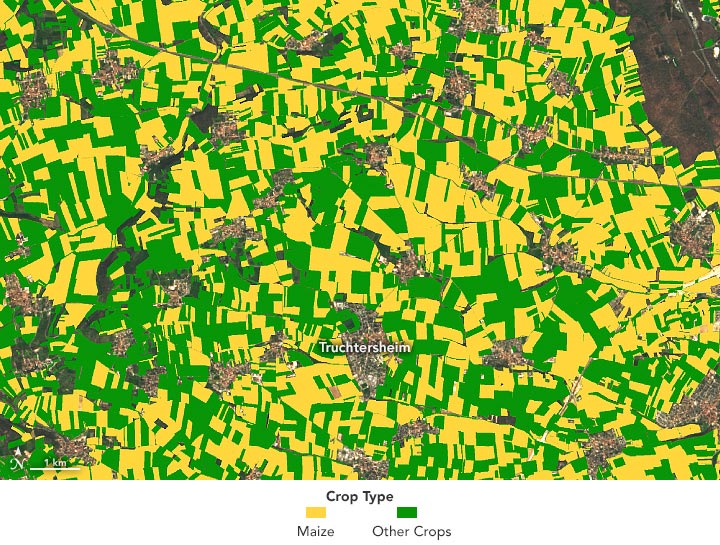

Un instrument conçu pour mesurer la hauteur des arbres peut également distinguer le maïs des autres cultures.

Chaque seconde, des lasers montés sur la Station spatiale internationale envoient 242 impulsions rapides de lumière vers la Terre. Ces faisceaux inoffensifs provenant de ;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) instrument bounce off Earth’s natural and human-made surfaces and are reflected back to the instrument. By measuring the time it takes for the signals to come back, scientists can derive the height of the surface below.

Scientists use these light detection and ranging, or lidar, measurements to create three-dimensional profiles of Earth’s surface. GEDI’s primary mission is to measure tree heights and forest structure in order to estimate the amount of carbon stored in forests and mangroves. New research supported by NASA Harvest reveals these data also can be used to map where different types of crops are being grown.

When David Lobell, an agricultural ecologist at Stanford University, saw researchers using GEDI data to estimate tree heights, he wondered how he could use the data to study agriculture. Stefania Di Tommaso and Sherrie Wang, researchers on his team, came up with the idea of using the data to distinguish different types of crops growing on farms.

Wang reached out to the GEDI science team at the University of Maryland to see if they were using the instrument for agricultural research. They responded that they were not sure GEDI data could be used for such an application. “But they did not say it was impossible,” said Lobell, who helps lead crop yield studies for NASA Harvest.

Mapping where certain crops are grown is important for estimating the overall production of the world’s major crops. But it has been difficult to reliably map crop types from space because many plants can look the same in optical imagery.

Lobell and his team started with corn (maize). When fully grown, average corn stalks are about a meter taller than other crops, a difference that is detectable in GEDI profiles. Using this insight, the Stanford team combined the lidar profile data from GEDI with optical imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellites. They were able to remotely map corn in three regions where there was reliable ground-based data to validate their observations: the state of Iowa in the U.S., the province of Jilin in China, and the region of Grand Est in France.

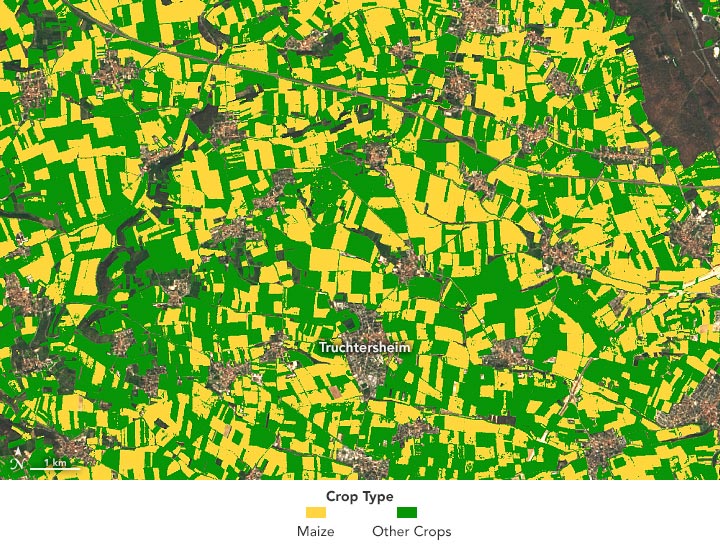

The images at the top of the page show the distribution of corn and other crops near Truchtersheim, France, as measured from the ground (top image) and from the GEDI-Sentinel model (lower image). The images below show the same technique applied to the three study sites.

2019

The Stanford algorithm correctly distinguished corn from other crops with an accuracy above 83 percent. The model using Sentinel-2 data alone had an overall average accuracy of 64 percent. “Two years ago, I never would have thought that GEDI could be used in this way,” Lobell said.

In the future, the research team aims to map corn production around the world, which could be used to understand the harvest prospects of corn each year. It could also help farmers and aid agencies assess food security concerns and get a sense of possible changes in management that could improve production in major corn-producing regions.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using data from DiTommaso et al. (2021) and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Emily Cassidy, NASA Earthdata.