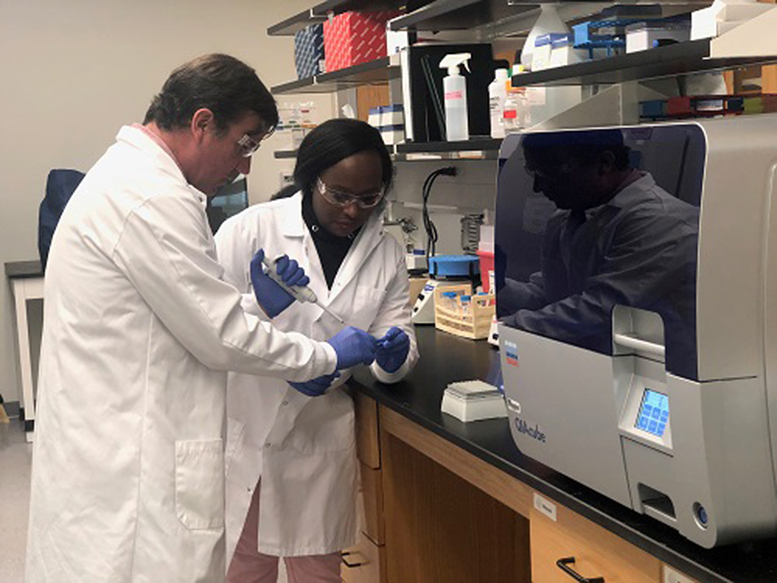

Le professeur Derek Wildman de l’USF et Clarisse Mussanabaganwa, chercheuse invitée de l’Université du Rwanda, mènent des recherches à l’USF. Crédit : Université de Floride du Sud

Les scientifiques du programme de génomique et du Centre de recherche sur la santé mondiale et les maladies infectieuses de l’USF ont franchi une étape importante en fournissant au peuple rwandais les outils scientifiques dont il a besoin pour aider à résoudre les problèmes de santé mentale découlant des génocides de 1994 contre le groupe ethnique des Tutsis.

Dans une étude inédite, les professeurs Monica Uddin et Derek Wildman du College of Public Health ont examiné l’ensemble du génome de femmes Tutsi enceintes vivant au Rwanda au moment du génocide et de leur progéniture et ont comparé leur DNA to other Tutsi women pregnant at the same time and their offspring, who were living in other parts of the world.

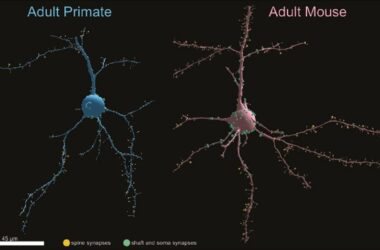

In the study published in “Epigenomics,” they found that the terror of genocide was associated with chemically modifications to the DNA of genocide-exposed women and their offspring. Many of these modifications occurred in genes previously implicated in risk for mental disorders such as PTSD and depression. These findings suggest that, unlike gene mutations, these chemical “epigenetic” modifications can have a rapid response to trauma across generations.

“Epigenetics refers to stable, but reversible, chemical modifications made to DNA that help to control a gene’s function,” Uddin said. “These can happen in a shorter time frame than is needed for changes to the underlying DNA sequence of genes. Our study found that prenatal genocide exposure was associated with an epigenetic pattern suggestive of reduced gene function in offspring.”

The team, which includes Clarisse Musanabaganwa, a visiting scholar from the University of Rwanda and her colleagues, came to their conclusion following the review of DNA from blood samples from 59 individuals – about half exposed personally or exposed in utero to the genocide. Exposure is defined as being impacted by genocide-related trauma, such as rape or evading capture, witnessing murder or serious attack with a weapon, and seeing dead and mutilated bodies.

The novel study is part of a larger consortium, the Human, Heredity & Health in Africa (H3), which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. It’s an effort to empower scientists in Africa in genomics, increasing their independence and ability to build the infrastructure needed to enhance genetic studies across the continent, and ultimately better capture data on the human genome across the world.

“The Rwandan people who are in this study and community as a whole really want to know what happened to them because there’s a lot of PTSD and other mental health disorders in Rwanda and people want answers as to why they’re experiencing these feelings and having these issues,” Wildman said.

While this study looks specifically at the impact of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, it supports previous studies that show what occurs during pregnancy when one is a fetus can have long-term impacts – many symptoms not appearing until later in life. Such evidence proves the need to enhance efforts to protect the safety and emotional and psychological wellbeing of pregnant women.

Researchers point out that individuals who were in utero during the genocide are starting to have children of their own and they hope to soon look at whether or not that trauma has had an epigenetic impact on the third generation. They’re now awaiting a new, larger batch of DNA samples to find out how trauma can impact risk for specific mental health disorders, like PTSD.

Reference: “Leukocyte methylomic imprints of exposure to the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda: a pilot epigenome-wide analysis” by Clarisse Musanabaganw, Agaz H Wani, Janelle Donglasan, Segun Fatumo, Stefan Jansen, Jean Mutabaruka, Eugene Rutembesa, Annette Uwineza, Erno J Hermans, Benno Roozendaal, Derek E Wildman, Leon Mutesa and Monica Uddin, 8 December 2021, Future Medicine.

DOI: 10.2217/epi-2021-0310

![Surfside Champlain Towers South Condo Collapse et la science du béton [Video]](https://7zine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/1635269596_Surfside-Champlain-Towers-South-Condo-Collapse-et-la-science-du-380x250.jpg)