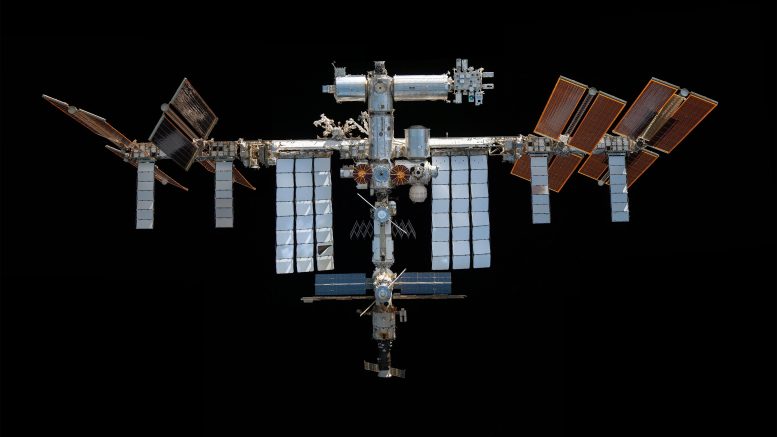

Le programme de la station spatiale internationale réunit des équipages internationaux, plusieurs véhicules de lancement, des installations de lancement, d’exploitation, de formation, d’ingénierie et de développement réparties dans le monde entier, des réseaux de communication et la communauté internationale des chercheurs scientifiques.

Lancée en 1998 et impliquant les États-Unis, la Russie, le Canada, le Japon et les pays participants de l’Agence spatiale européenne, la Station spatiale internationale est l’une des collaborations internationales les plus complexes jamais entreprises.

Q. Qui exploite la station spatiale internationale ?

Cinq agences partenaires (l’Agence spatiale canadienne, l’Agence spatiale européenne, l’Agence japonaise d’exploration aérospatiale, la National Aeronautics and Space Administration et la State Space Corporation “Roscosmos”) exploitent la Station spatiale internationale, chaque partenaire étant responsable de la gestion et du contrôle du matériel qu’il fournit. La station a été conçue pour être interdépendante et son fonctionnement dépend des contributions de tous les partenaires. Aucun des partenaires n’a actuellement la capacité de fonctionner sans les autres.

La station spatiale n’a pas été conçue pour être démontée, et les interdépendances actuelles entre chaque segment de la station empêchent le segment orbital américain et le segment russe de fonctionner indépendamment. Les tentatives de détachement du segment orbital américain et du segment russe se heurteraient à d’importants problèmes de logistique et de sécurité étant donné la multitude de connexions externes et internes, la nécessité de contrôler l’attitude et l’altitude du vaisseau spatial et l’interdépendance des logiciels.

Q. Quels sont les exemples d’interdépendance de la Station spatiale internationale ?

Les exemples incluent :

- La Russie fournit toute la propulsion de la Station spatiale internationale utilisée pour la relance de la station, le contrôle d’attitude, les manœuvres d’évitement des débris et les éventuelles opérations de désorbitation par le segment russe, les systèmes de propulsion russes et le vaisseau cargo de réapprovisionnement Progress.

- Le propergol pour les propulseurs du segment russe est fourni par le vaisseau cargo russe Progress.

- Les gyroscopes américains assurent le contrôle d’attitude au jour le jour pour contrôler l’orientation de la station. Les propulseurs russes sont utilisés pour le contrôle d’attitude lors d’événements dynamiques, comme l’amarrage des vaisseaux spatiaux, et permettent de récupérer le contrôle d’attitude lorsque les gyroscopes atteignent leurs limites de contrôle.

- L’énergie des panneaux solaires américains est transférée au segment russe pour augmenter leurs besoins en énergie.

- ;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellites (TDRS) provide communications and data transfer capability between the ground and the entire station, with some additional, less-continuous capability through Russian ground stations and satellites.

- There are life support systems on both the U.S. Orbital Segment and Russian Segment, responsible for generating oxygen and scrubbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This allows space station to have more crew on board, and having dissimilar systems enables increased levels of safety for crew.

- Mission control centers for NASA in Houston and Roscosmos in Moscow only command and control their respective segments.

Q. What areas of Earth does the International Space Station fly over?

The International Space Station orbits with an inclination of 51.6 degrees. This means that, as it orbits, the farthest north and south of the Equator it will ever go is 51.6 degrees latitude. An explanation and visuals of the space station orbit is available online.

On the Spot The Station page, you can enter a country or region to watch the International Space Station pass overhead from several thousand worldwide locations.

Q. Can astronauts fly to the International Space Station on one type of spacecraft and return on a different one?

Astronauts typically launch and return in the same type of spacecraft (i.e., Crew Dragon or Soyuz). Each astronaut has custom hardware including a launch and entry suit or a seat liner that is not interchangeable between different models of spacecraft. A crew member can launch on one Russian Soyuz and return on a different Soyuz, but transferring them to return on a SpaceX Dragon would require a different launch and entry suit that is custom fitted and created on the ground. NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei has transferred seat liners between Soyuz spacecraft on his record setting mission.

Q. Do NASA and Roscosmos always need its astronauts or cosmonauts on the International Space Station?

Operating the space station requires physical, hands-on maintenance by the crew, on both U.S. Operating Segment and the Russian Segment, to ensure systems continue functioning. NASA and Roscosmos crew members are not trained to operate each other’s respective segments without onboard assistance. In failure scenarios on the United States Orbital Segment, only U.S. astronauts are trained to fully respond, either through actions inside the station (e.g., to change out a component) or through spacewalks. The same is true for Russian cosmonauts in failure situations originating on the Russian segment.

Q. How is the International Space Station’s attitude and altitude controlled and can any current functions be replaced or upgraded?

All International Space Station propulsion is provided by the Russian Segment and Russian cargo spacecraft. Propulsion is used for station reboost, attitude control, debris avoidance maneuvers and eventual deorbit operations are handled by the Russian Segment and Progress cargo craft. The U.S. gyroscopes provide day-to-day attitude control or controlling the orientation of the station. Russian thrusters are used for attitude control during dynamic events like spacecraft dockings and provide attitude control recovery when the gyroscopes reach their control limits.

Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus is the only U.S. commercial spacecraft currently in testing to provide limited capability for future reboosts. This capability relies on the Russian Segment for attitude control during the small reboost. It does not currently have the capability to replace attitude control functions for the space station or carry adequate propellant for long-term sustained operations.

Attitude control and propulsive reboost capability is a continuous requirement, which means the space station needs a continuous and steady supply of propulsion spacecraft. Changes to the current propulsion scheme would take considerable new hardware/software development, and significant time and funding to enact.

Q. How long do all the International Space Station partners plan to operate the complex?

NASA and its international partners have maintained a continuous and productive human presence aboard the International Space Station for more than 21 years. Life extension analysis for the US Segment has been completed through 2028 with no issues that would prevent space station from being further extended. The United States has committed to extend International Space Station operations through 2030. NASA’s space agency partners have all recommended International Space Station extension through 2030 with approvals pending through their own government processes.

Q. How will NASA and Roscosmos safely deorbit the International Space Station after its planned decommissioning?

The primary objective during space station deorbit operations is the safe re-entry of the space station’s structure into an unpopulated area in the ocean as outlined in the agency’s International Space Station transition plan.

The space station will accomplish the deorbit maneuvers by using the propulsive capabilities of the space station and its visiting spacecraft. NASA and its partners have evaluated varying quantities of Russian Progress spacecraft to support deorbit operations. Additionally, NASA is evaluating whether U.S. commercial spacecraft can be modified to provide capability to deorbit the space station.