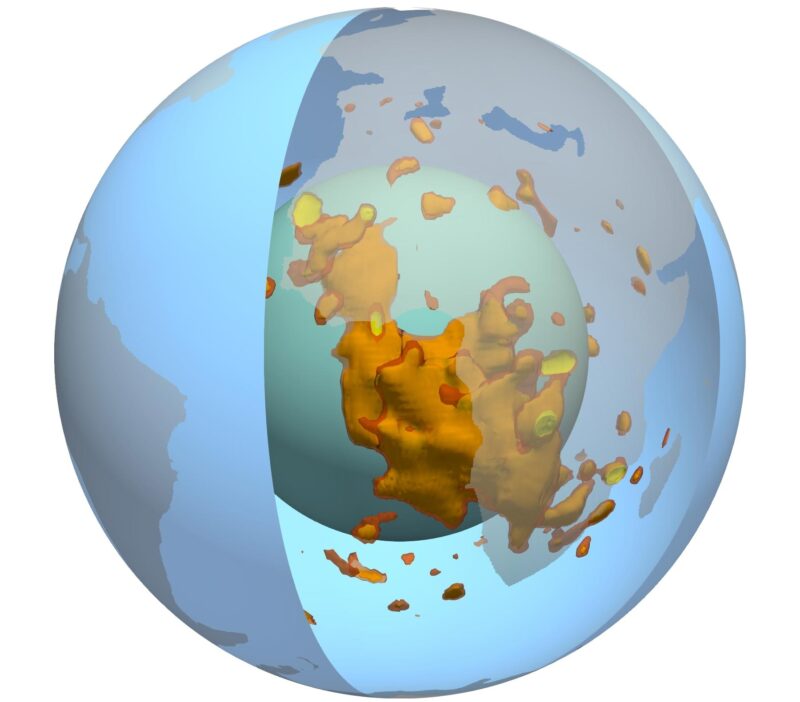

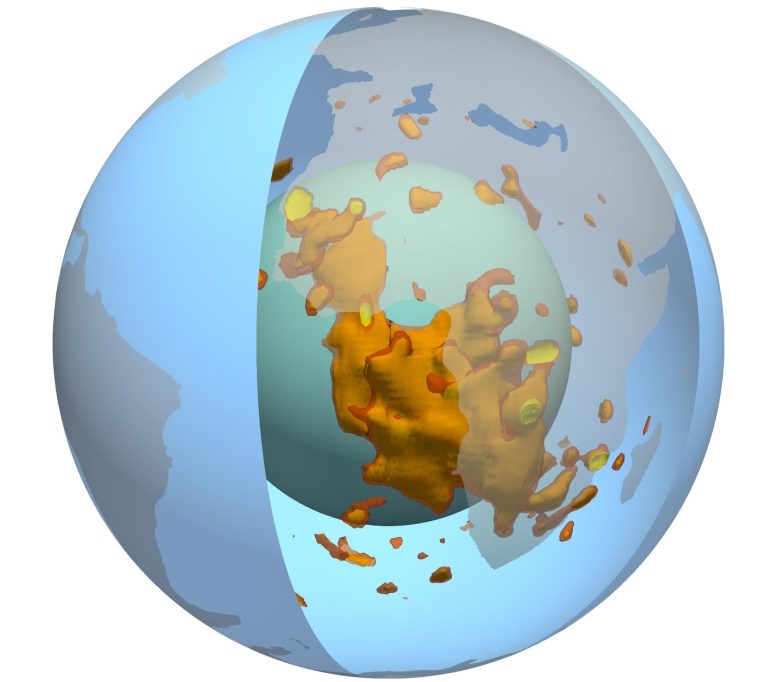

Une vue en 3D du blob dans le manteau terrestre sous l’Afrique, représenté par les couleurs rouge-jaune-orange. La couleur cyan représente la limite noyau-manteau, le bleu la surface et le gris transparent les continents. Crédit : Mingming Li/ASU

La Terre est superposée comme un oignon, avec une fine croûte externe, un manteau visqueux épais, un noyau externe fluide et un noyau interne solide. Dans le manteau, il y a deux structures massives ressemblant à des blobs, à peu près sur les côtés opposés de la planète. Les protubérances, plus officiellement appelées grandes provinces à faible cisaillement (LLSVP), ont chacune la taille d’un continent et sont 100 fois plus hautes que le mont Everest. L’une se trouve sous le continent africain, tandis que l’autre se trouve sous l’océan Pacifique.

En utilisant des instruments qui mesurent les ondes sismiques, les scientifiques savent que ces deux blobs ont des formes et des structures compliquées, mais malgré leurs caractéristiques proéminentes, on sait peu de choses sur l’existence de ces blobs ou sur ce qui a conduit à leurs formes étranges.

Les scientifiques de l’Université d’État de l’Arizona, Qian Yuan et Mingming Li, de l’École d’exploration de la Terre et de l’espace, ont entrepris d’en apprendre davantage sur ces deux blobs en utilisant la modélisation géodynamique et les analyses des études sismiques publiées. Grâce à leurs recherches, ils ont pu déterminer la hauteur maximale atteinte par les blobs et la manière dont le volume et la densité des blobs, ainsi que la viscosité environnante dans le manteau, peuvent contrôler leur hauteur. Leurs recherches ont été récemment publiées dans Il a été créé en janvier 2008.

;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>Nature Geoscience.

The results of their seismic analysis led to a surprising discovery that the blob under the African continent is about 621 miles (1,000 km) higher than the blob under the Pacific Ocean. According to Yuan and Li, the best explanation for the vast height difference between the two is that the blob under the African continent is less dense (and therefore less stable) than the one under the Pacific Ocean.

To conduct their research, Yuan and Li designed and ran hundreds of mantle convection models simulations. They exhaustively tested the effects of key factors that may affect the height of the blobs, including the volume of the blobs and the contrasts of density and viscosity of the blobs compared with their surroundings. They found that to explain the large differences of height between the two blobs, the one under the African continent must be of a lower density than that of the blob under the Pacific Ocean, indicating that the two may have different composition and evolution.

“Our calculations found that the initial volume of the blobs does not affect their height,” lead author Yuan said. “The height of the blobs is mostly controlled by how dense they are and the viscosity of the surrounding mantle.”

“The Africa LLVP may have been rising in recent geological time,” co-author Li added. “This may explain the elevating surface topography and intense volcanism in eastern Africa.”

These findings may fundamentally change the way scientists think about the deep mantle processes and how they can affect the surface of the Earth. The unstable nature of the blob under the African continent, for example, may be related to continental changes in topography, gravity, surface volcanism and plate motion.

“Our combination of the analysis of seismic results and the geodynamic modeling provides new insights on the nature of the Earth’s largest structures in the deep interior and their interaction with the surrounding mantle,” Yuan said. “This work has far-reaching implications for scientists trying to understand the present-day status and the evolution of the deep mantle structure, and the nature of mantle convection.”

Reference: “Instability of the African large low-shear-wave-velocity province due to its low intrinsic density” by Qian Yuan and Mingming Li, 10 March 2022, Nature Geoscience.

DOI: 10.1038/s41561-022-00908-3