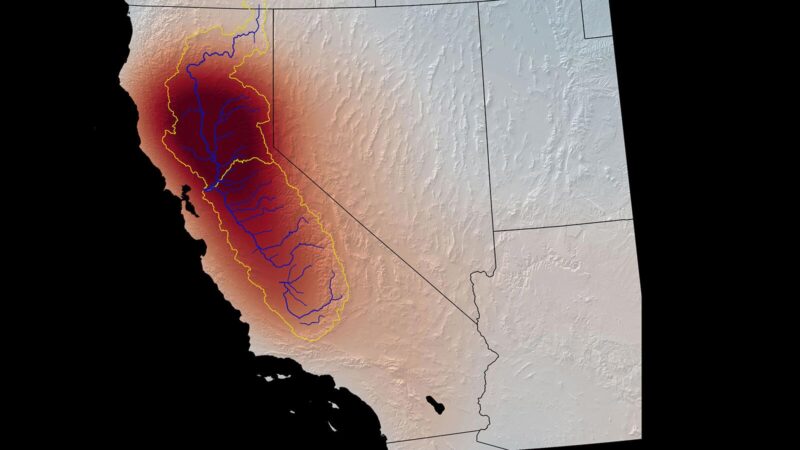

L’irrigation par les eaux souterraines permet aux agriculteurs de faire pousser des cultures luxuriantes dans la vallée centrale de la Californie, mais les ressources en eau souterraine diminuent. Une étude de la NASA propose un nouvel outil pour gérer les eaux souterraines. Crédit : Département californien des ressources en eau/Dale Kolke

Les chercheurs ont démêlé des modèles déconcertants d’affaissement et d’élévation des terres pour localiser les endroits souterrains où l’eau est pompée pour l’irrigation.

Les scientifiques ont mis au point une nouvelle méthode qui promet d’améliorer la gestion des eaux souterraines, essentielles à la vie et à l’agriculture dans les régions sèches. La méthode permet de déterminer la part des pertes d’eau souterraine provenant des aquifères confinés dans l’argile, qui peuvent être drainés si sec qu’ils ne se reconstitueront pas, et la part provenant du sol qui n’est pas confiné dans un aquifère, qui peut être réapprovisionné par quelques années de pluies normales.

L’équipe de recherche a étudié le bassin de Tulare en Californie, qui fait partie de la Central Valley. L’équipe a découvert que la clé de la distinction entre ces sources d’eau souterraines est liée aux schémas d’abaissement et d’élévation du niveau du sol dans cette région agricole fortement irriguée.

La Central Valley ne représente que 1 % des terres agricoles des États-Unis, mais elle produit annuellement 40 % des fruits de table, légumes et noix du pays. Une telle productivité n’est possible que parce que les agriculteurs augmentent les 12 à 25 centimètres de précipitations annuelles de la vallée par un pompage intensif des eaux souterraines. Les années de sécheresse, plus de 80 % de l’eau d’irrigation provient du sous-sol.

Après des décennies de pompage, les ressources en eau souterraine s’amenuisent. Les puits du bassin de Tulare doivent maintenant être forés à une profondeur de plus de 1 000 mètres pour trouver de l’eau en quantité suffisante. Il n’y a aucun moyen de mesurer exactement la quantité d’eau qui reste dans le sous-sol, mais les gestionnaires doivent en faire l’usage le plus judicieux possible. Pour cela, il faut vérifier si l’eau est puisée dans les aquifères ou dans le sol meuble, appelé la nappe phréatique. Dans cette grande région qui compte des dizaines de milliers de puits sans compteur, la seule façon pratique de le faire est d’utiliser des données satellitaires.

Une équipe de recherche de ;” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory in Northern California set out to create a method that would do exactly that. They attacked the problem by combining data on water loss from U.S.-European Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and GRACE Follow-On satellites with data on ground-level changes from a ESA (European Space Agency) Sentinel-1 satellite. Ground-level changes in this region are often related to water loss because when ground is drained of water, it eventually slumps together and sinks into the spaces where water used to be – a process called subsidence.

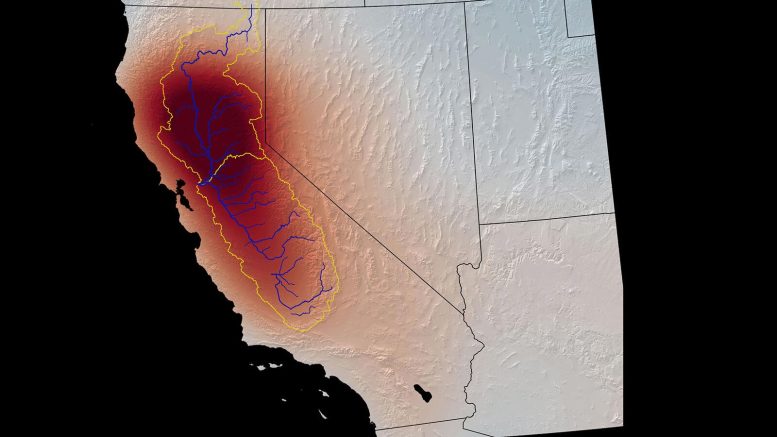

This map shows changes in the mass of water, both above ground and underground, in California from 2003 to 2013, as measured by NASA’s GRACE satellite. The darkest red indicates the greatest water loss. The Central Valley is outlined in yellow; the Tulare Basin covers about the southern third. Extreme groundwater depletion has continued to the present. Credit: NASA/GSFC/SVS

The Tulare Basin is subsiding drastically: The current rate is about one foot (0.3 meters) of sinkage per year. But from one month to the next, the ground may drop, rise or stay the same. What’s more, these changes don’t always line up with expected causes. For example, after a heavy rainfall, the water table rises. It seems obvious that this would cause the ground level to rise, too, but it sometimes sinks instead.

The researchers thought these mysterious short-term variations might hold the key to determining the sources of pumped water. “The main question was, how do we interpret the change that’s happening on these shorter time scales: Is it just a blip, or is it important?” said Kyra Kim, a postdoctoral fellow at JPL and coauthor of the paper, which appeared in Scientific Reports.

Clay vs. Sand

Kim and her colleagues believed the changes were related to the different kinds of soils in the basin. Aquifers are confined by layers of stiff, impermeable clay, whereas unconfined soil is looser. When water is pumped from an aquifer, the clay takes a while to compress in response to the weight of land mass pressing down from above. Unconfined soil, on the other hand, rises or falls more quickly in response to rain or pumping.

The researchers created a simple numerical model of these two layers of soils in the Tulare Basin. By removing the long-term subsidence trend from the ground-level-change data, they produced a dataset of only the month-to-month variations. Their model revealed that on this time scale, virtually all of the ground-level change can be explained by changes in aquifers, not in the water table.

For example, in spring, there’s little rainfall in the Central Valley, so the water table is usually sinking. But runoff from snow in the Sierra Nevada is recharging the aquifers, and that causes the ground level to rise. When rainfall is causing the water table to rise, if the aquifers are compressing at the same time from being pumped during the preceding dry season, the ground level will fall. The model correctly reproduced the effects of weather events like heavy rainfalls in the winter of 2016-17. It also matched the small amount of available data from wells and GPS.

Kim pointed out that the new model can be repurposed to represent other agricultural regions where groundwater use needs to be better monitored. With a planned launch in 2023, the NASA-ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation) Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR) mission will measure changes in ground level at even higher resolution than Sentinel-1. Researchers will be able to combine NISAR’s dataset with data from GRACE Follow-On in this model for the benefit of agriculture around the globe. “We’re heading toward a really beautiful marriage between remote sensing and numerical models to bring everything together,” Kim said.

Reference: “Using Sentinel-1 and GRACE satellite data to monitor the hydrological variations within the Tulare Basin, California” by Donald W. Vasco, Kyra H Kim, Tom G. Farr, J. T. Reager, David Bekaert, Simran S. Sangha, Jonny Rutqvist and Hiroko K. Beaudoing, 9 March 2022, Scientific Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-07650-1