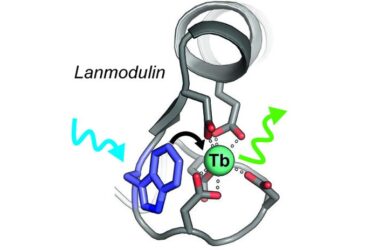

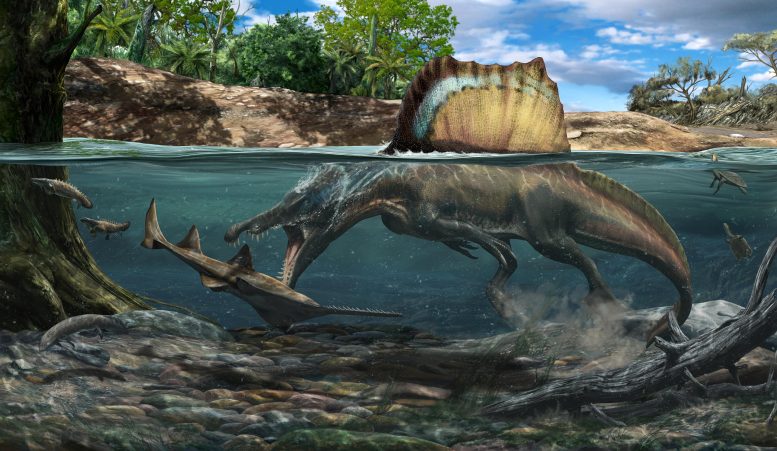

Spinosaurus, le plus long dinosaure prédateur connu, ouvre ses mâchoires allongées, constellées de dents coniques, pour attraper une scie. Contrairement à ce qui avait été suggéré, cet animal n’était pas un échassier ressemblant à un héron – c’était un “monstre des rivières”, qui poursuivait activement ses proies dans un vaste système fluvial situé dans l’actuelle Afrique du Nord. Les os denses du squelette de Spinosaurus suggèrent fortement qu’il passait beaucoup de temps immergé dans l’eau. Crédit : Davide Bonadonna

Spinosaurus est le plus grand dinosaure prédateur connu – plus de deux mètres de plus que le plus long des dinosaures de l’Arctique. Tyrannosaurus rex – mais la façon dont il chassait a fait l’objet de débats pendant des décennies.

Dans un nouvel article, publié le 23 mars 2022, dans la revue Nature, un groupe de paléontologues a adopté une approche différente pour déchiffrer le mode de vie de créatures éteintes depuis longtemps : l’examen de la densité de leurs os.

En analysant la densité des os de spinosauridés et en les comparant à d’autres animaux comme les pingouins, les hippopotames et les alligators, l’équipe a découvert que Spinosaurus et son proche parent Baryonyx de la Cretaceous of the UK both had dense bones that would have allowed them to submerge themselves underwater to hunt.

Scientists already knew that spinosaurids had certain affinities with water — their elongate jaws and cone-shaped teeth are similar to those of fish-eating predators, and the ribcage of Baryonyx, from Surrey, even contained half-digested fish scales.

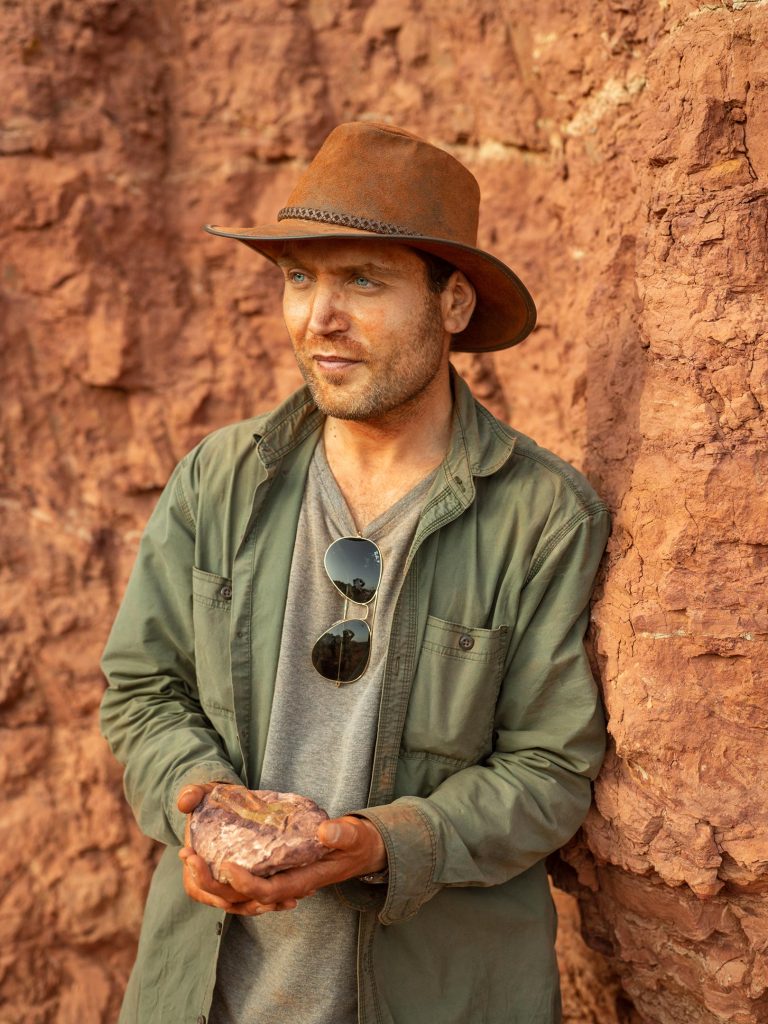

In the last decade, University of Portsmouth paleontologist and National Geographic Explorer Dr. Nizar Ibrahim unearthed different parts of a Spinosaurus skeleton in North Africa’s Sahara Desert. The skeleton Dr. Ibrahim and his team described had retracted nostrils, short hind legs, paddle-like feet, and a fin-like tail: all signs that firmly pointed to an aquatic lifestyle.

Dr. Ibrahim said: “We battled sandstorms, flooding, snakes, scorpions, and more to excavate the most enigmatic dinosaur in the world and now we have multiple lines of evidence all pointing in the same direction – the skeleton really has “water-loving dinosaur” written all over it!”

Baryonyx, from Surrey in England, swims through an ancient river with a fish in its jaws. Like its much larger African relative Spinosaurus, Baryonyx had dense bones, suggesting that it too spent much of its time submerged in water. It was previously thought to have been less aquatic than its Saharan relative. Credit: Davide Bonadonna

Based on its highly specialized anatomy, Dr. Ibrahim and his team previously suggested that Spinosaurus could swim and actively pursue prey in the water, but others claimed that it was not much of a swimmer and instead waded in the water like a giant heron.

Researchers have continued to debate whether Spinosaurus spent much of its time submerged, pursuing prey in the water, or if it just stood in the shallows and dipped its jaws in to snap up prey.

“In part this is probably because we were challenging decade-old dogma – so even if you have a very strong case, you kind of expect a certain degree of pushback,” Dr Ibrahim said.

This continuing debate led lead author Dr. Matteo Fabbri, based at Chicago’s Field Museum, senior author Dr. Ibrahim and an international team of researchers to try to find another way to infer the lifestyle and ecology of long-extinct creatures like Spinosaurus.

Dr. Nizar Ibrahim. Credit: Paolo Verzone

Dr. Fabbri said: “The idea for our study was, okay, clearly we can interpret the fossil data in different ways. But what about the general physical laws? There are certain laws that are applicable to any organism on this planet. One of these laws regards density and the capability of submerging into water.”

Across the animal kingdom, bone density can tell us whether an animal is able to sink beneath the surface and swim.

“Previous studies have shown that mammals adapted to water have dense, compact bone in their postcranial (behind the skull) skeletons,” said Fabbri, an expert on the internal structure of bone. Dense bone helps with buoyancy control and allows the animal to submerge itself.

The team assembled a very large dataset of femur and rib bone cross-sections from 250 species of extinct and living animals, including both land-dwellers and water-dwellers, and covering animals ranging in weight from a few grams to several tonnes including seals, whales, elephants, mice, and even hummingbirds.

They also collected data on extinct marine reptiles like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. The researchers compared bone cross sections of these animals to cross-sections of bone from Spinosaurus and its relatives Baryonyx and Suchomimus.

Dr. Ibrahim said: “The scope of our study kept expanding because we kept thinking of more and more groups of vertebrates to include.”

The scientists found a clear link between bone density and aquatic foraging behavior: animals that submerge themselves underwater to find food have bones that are almost completely solid throughout, whereas cross-sections of land-dwellers’ bones look more like doughnuts, with hollow centers.

When the researchers applied spinosaurid dinosaur bones to this paradigm, they found that Spinosaurus and Baryonyx both had the type of dense bone associated with full submersion.

Meanwhile, the closely related African Suchomimus had hollower bones. It still lived by water and ate fish, as evidenced by its crocodile-like snout and conical teeth, but based on its bone density, it wasn’t actually swimming much. “That was a bit of a surprise” according to Ibrahim, “because Baryonyx and Suchomimus look rather similar”. But the team soon realized that it was not out of the ordinary and similar patterns can be seen in other groups.

Other dinosaurs, like the giant long-necked sauropods also had some dense bones in their limbs, but this simply reflects the huge amount of stress on those limb bones.

Dr. Ibrahim said: “Some of these animals would have weighed as much as several elephants so adding extra load-bearing capacity to the bones makes a lot of sense!”

Dr. Jingmai O’Connor, a curator at the Field Museum and co-author of this study, says that collaborative studies like this one that draw from hundreds of specimens, are “the future of paleontology. They’re very time-consuming to do, but they let scientists shed light onto big patterns.”

Dr. Ibrahim is already thinking about the next questions. “I think that, with this additional line of evidence, speculative notions that envisage Spinosaurus as some sort of giant wader lack evidential support and can be safely excluded. The bones don’t lie, and now we know than even the internal architecture of the bones is entirely consistent with our interpretation of this animal as a giant predator hunting fish in vast rivers, using its paddle-like tail for propulsion. It will be interesting to reconstruct in a lot more detail how these river monsters moved around – something we are already working on.”

For more on this research, see Dense Bones Allowed Spinosaurus – The Biggest Carnivorous Dinosaur Ever Discovered – To Hunt Underwater.

Reference: “Subaqueous foraging among carnivorous dinosaurs” by Matteo Fabbri, Guillermo Navalón, Roger B. J. Benson, Diego Pol, Jingmai O’Connor, Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, Gregory M. Erickson, Mark A. Norell, Andrew Orkney, Matthew C. Lamanna, Samir Zouhri, Justine Becker, Amanda Emke, Cristiano Dal Sasso, Gabriele Bindellini, Simone Maganuco, Marco Auditore and Nizar Ibrahim, 23 March 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04528-0