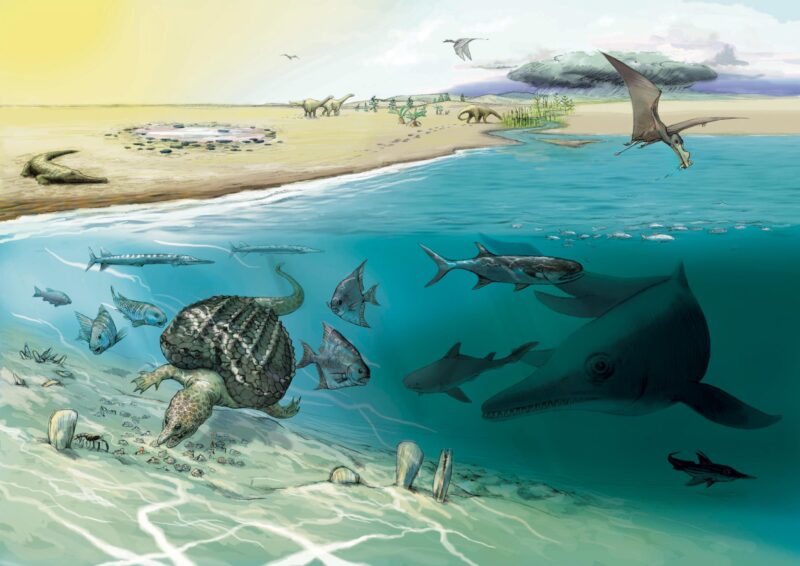

Des dépôts vieux de 200 millions d’années du précurseur de la mer Méditerranée ont été préservés dans les Hautes-Alpes suisses. Les ichtyosaures de la taille d’une baleine ne venaient de la haute mer qu’occasionnellement dans des eaux moins profondes. Crédit : Jeannette Rüegg/Heinz Furrer, Université de Zurich

La plus grande dent d’ichtyosaure jamais découverte fait partie des découvertes fossiles, y compris les restes d’une nouvelle bête, plus longue qu’une piste de bowling.

Des paléontologues ont découvert des ensembles de fossiles représentant trois nouveaux ichtyosaures qui pourraient avoir été parmi les plus grands animaux ayant jamais vécu, selon un nouvel article de recherche publié le 27 avril 2022 dans la revue à comité de lecture . Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (Journal de la paléontologie des vertébrés)..

Mise au jour dans les Alpes suisses entre 1976 et 1990, cette découverte comprend la plus grande dent d’ichtyosaure jamais trouvée. La largeur de la racine de la dent est deux fois plus grande que celle de tout reptile aquatique connu, la plus grande précédente appartenant à un ichtyosaure de 15 mètres (50 pieds) de long.

D’autres restes squelettiques incomplets comprennent la plus grande vertèbre du tronc en Europe, qui montre un autre ichtyosaure rivalisant avec le plus grand fossile de reptile marin connu aujourd’hui, l’ichtyosaure de 21 mètres (69 pieds) de long.Shastasaurus sikkanniensis. de la Colombie britannique, Canada.

La racine de la dent trouvée a un diamètre de 60 millimètres (~2.4 inches). Cela en fait la dent d’ichtyosaure la plus épaisse trouvée à ce jour. Crédit : Rosi Roth/Université de Zurich

Le Dr Heinz Furrer, co-auteur de cette étude, faisait partie d’une équipe qui a récupéré les fossiles lors de travaux de cartographie géologique dans la formation de Kössen, dans les Alpes. Plus de 200 millions d’années auparavant, les couches rocheuses recouvraient encore le fond de la mer. Mais avec le plissement des Alpes, elles s’étaient retrouvées à une altitude de 2 800 mètres !

Aujourd’hui conservateur retraité de l’Institut et du Musée paléontologiques de l’Université de Zurich, le Dr Furrer s’est dit ravi d’avoir mis au jour “l’ichtyosaure le plus long du monde, avec la dent la plus épaisse trouvée à ce jour et la plus grande vertèbre du tronc en Europe !”

Heinz Furrer avec la plus grande vertèbre d’ichtyosaure. Crédit : Rosi Roth/Université de Zurich

L’auteur principal, P. Martin Sandler, de l’Université de Bonn, espère “qu’il y a peut-être d’autres restes de créatures marines géantes cachés sous les glaciers”.

“Plus grand est toujours mieux”, dit-il. “Il y a des avantages sélectifs distincts à la grande taille du corps. La vie va y aller si elle le peut. Il n’y a que trois groupes d’animaux qui avaient une masse supérieure à 10-20 tonnes métriques : les dinosaures à long cou (sauropodes), les baleines et les ichtyosaures géants du Triassic.”

These monstrous, 80-ton reptiles patrolled Panthalassa, the World’s ocean surrounding the supercontinent Pangea during the Late Triassic, about 205 million years ago. They also made forays into the shallow seas of the Tethys on the eastern side of Pangea, as shown by the new finds.

Ichthyosaurs first emerged in the wake of the Permian extinction some 250 million years ago, when some 95 percent of marine species died out. The group reached its greatest diversity in the Middle Triassic and a few species persisted into the Cretaceous. Most were much smaller than S. sikanniensis and the similarly-sized species described in the paper.

Roughly the shape of contemporary whales, ichthyosaurs had elongated bodies and erect tail fins. Fossils are concentrated in North America and Europe, but ichthyosaurs have also been found in South America, Asia, and Australia. Giant species have mostly been unearthed in North America, with scanty finds from the Himalaya and New Caledonia, so the discovery of further behemoths in Switzerland represents an expansion of their known range.

Martin Sander and Michael Hautmann look over the discovery layers on the southern slope of Schesaplana, on the Graubünden/Vorarlberg border. Credit: © Jelle Heijne/University of Bonn

However, so little is known about these giants that there are mere ghosts. Tantalizing evidence from the UK, consisting of an enormous toothless jaw bone, and from New Zealand suggest that some of them were the size of blue whales. An 1878 paper credibly describes an ichthyosaur vertebrae 45 cm (~18 inches) in diameter from there, but the fossil never made it to London and may have been lost at sea. Sander notes that “it amounts to a major embarrassment for paleontology that we know so little about these giant ichthyosaurs despite the extraordinary size of their fossils. We hope to rise to this challenge and find new and better fossils soon.”

These new specimens probably represent the last of the leviathans. “In Nevada, we see the beginnings of true giants, and in the Alps the end,” says Sander, who also co-authored a paper last year about an early giant ichthyosaur from Nevada’s Fossil Hill. “Only the medium–to–large-sized dolphin – and orca-like forms survived into the Jurassic.”

Martin Sander with a rib of the larger skeleton. The estimated length of the animal is 20 meters. Credit: © Laurent Garbay/University of Bonn

While the smaller ichthyosaurs typically had teeth, most of the known gigantic species appear to have been toothless. One hypothesis suggests that rather than grasping their prey, they fed by suction. “The bulk feeders among the giants must have fed on cephalopods. The ones with teeth likely feed on smaller ichthyosaurs and large fish,” Sander suggests.

The tooth described by the paper is only the second instance of a giant ichthyosaur with teeth—the other being the 15-meter-long Himalayasaurus. These species likely occupied similar ecological roles to modern sperm whales and killer whales. Indeed, the teeth are curved inwards like those of their mammalian successors, indicating a grasping mode of feeding conducive to capturing prey such as giant squid.

“It is hard to say if the tooth is from a large ichthyosaur with giant teeth or from a giant ichthyosaur with average-sized teeth,” Sander wryly acknowledges. Because the tooth described in the paper was broken off at the crown, the authors were not able to confidently assign it to a particular taxon. Still, a peculiarity of dental anatomy allowed the researchers to identify it as belonging to an ichthyosaur.

“Ichthyosaurs have a feature in their teeth that is nearly unique among reptiles: the infolding of the dentin in the roots of their teeth,” explains Sander. “The only other group to show this are monitor lizards.”

The two sets of skeletal remains, which consist of a vertebrae and ten rib fragments, and seven asssociated vertebrae, have been assigned to the family Shastasauridae, which contains the giants Shastasaurus, Shonisaurus, and Himalayasaurus. Comparison of the vertebrae from one set suggests that they may have been the same size or slightly smaller than those of S. sikkanniensis. These measurements are slightly skewed by the fact that the fossils have been tectonically deformed—that is, they have literally been squashed by the movements of the tectonic plates whose collision led to their movement from a former sea floor to the top of a mountain.

Known as the Kössen Formation, the rocks from which these fossils derive were once at the bottom of a shallow coastal area—a very wide lagoon or shallow basin.

This adds to the uncertainty surrounding the habits of these animals, whose size indicates their suitability to deeper reaches of the ocean. “We think that the big ichthyosaurs followed schools of fish into the lagoon. The fossils may also derive from strays that died there,” suggests Furrer.

“You have to be kind of a mountain goat to access the relevant beds,” Sander laughs. “They have the vexing property of not occurring below about 8,000 feet, way above the treeline.”

“At 95 million years ago, the northeastern part of Gondwana, the African plate (which the Kössen Formation was part of), started to push against the European plate, ending with the formation of the very complex piles of different rock units (called “nappes”) in the Alpine orogeny at about 30–40 million years ago,” relates Furrer. So it is that these intrepid researchers found themselves picking through the frozen rocks of the Alps and hauling pieces of ancient marine monsters nearly down to sea level once again for entry into the scientific record.

Reference: “Giant Late Triassic ichthyosaurs from the Kössen Formation of the Swiss Alps and their paleobiological implications” by P. Martin Sander, Pablo Romero Pérez de Villar, Heinz Furrer and Tanja Wintrich, 27 April 2022, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2021.2046017