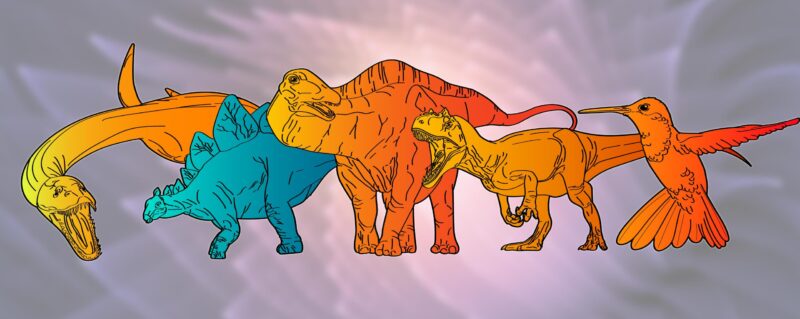

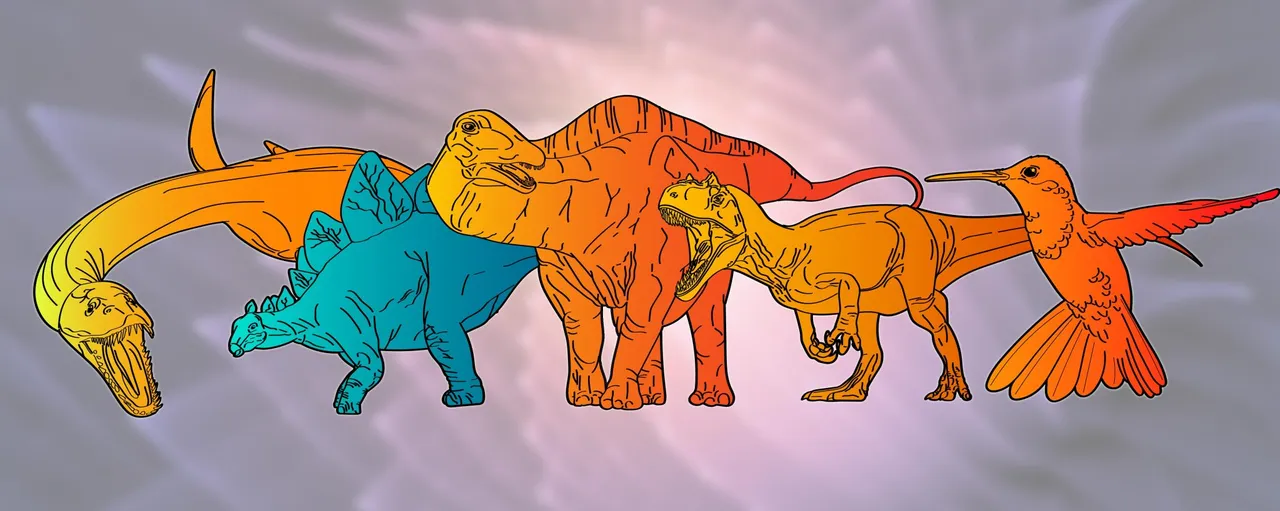

Dessin schématique d’un sous-ensemble d’animaux étudiés dans le cadre de la recherche. Les taux métaboliques et les stratégies thermophysiologiques qui en résultent sont codés par couleur, les teintes oranges caractérisant les taux métaboliques élevés coïncidant avec le sang chaud, et les teintes bleues les taux métaboliques faibles coïncidant avec le sang froid. De gauche à droite : Plesiosaurus, Stegosaurus, Diplodocus, Allosaurus, Calypte (colibri moderne). Crédit : J. Wiemann

Les paléontologues débattent depuis des décennies pour savoir si les dinosaures avaient le sang chaud, comme les mammifères et les oiseaux modernes, ou le sang froid, comme les reptiles modernes. Savoir si les dinosaures avaient le sang chaud ou le sang froid pourrait nous donner des indices sur leur degré d’activité et leur vie quotidienne, mais les méthodes précédentes pour déterminer leur sang chaud ou froid – la vitesse à laquelle leur métabolisme pouvait transformer l’oxygène en énergie – n’étaient pas concluantes. Cependant, dans un nouvel article publié dans la revue Natureles scientifiques dévoilent une nouvelle méthode pour étudier les taux métaboliques des dinosaures, en utilisant des indices dans leurs os qui indiquent combien les animaux individuels ont respiré pendant leur dernière heure de vie.

“La question de savoir si les dinosaures avaient le sang chaud ou froid est l’une des plus anciennes questions de la paléontologie, et nous pensons maintenant avoir un consensus sur le fait que la plupart des dinosaures avaient le sang chaud”, déclare Jasmina Wiemann, auteur principal de l’article et chercheur postdoctoral à l’Institut de technologie de Californie (Caltech).

“Le nouveau proxy développé par Jasmina Wiemann nous permet de déduire directement le métabolisme d’organismes disparus, ce dont nous ne faisions que rêver il y a quelques années. Nous avons également constaté que différents taux métaboliques caractérisaient différents groupes, ce qui avait été suggéré précédemment sur la base d’autres méthodes, mais jamais testé directement”, déclare Matteo Fabbri, chercheur postdoctoral au Field Museum de Chicago et l’un des auteurs de l’étude.

Les gens parlent souvent du métabolisme en termes de la facilité avec laquelle une personne peut rester en forme, mais à la base, “le métabolisme est l’efficacité avec laquelle nous convertissons l’oxygène que nous respirons en énergie chimique qui alimente notre corps”, explique Wiemann, qui est affilié à l’université de Yale et au Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

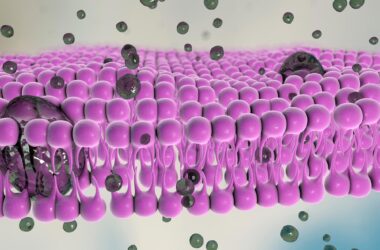

Vue microscopique de tissus mous extraits des os d’un des spécimens de dinosaures (Allosaurus) qui ont été étudiés pour détecter des signaux métaboliques (liaisons transversales métaboliques) dans les produits de fossilisation de la matrice osseuse protéique. La fossilisation introduit des réticulations supplémentaires qui, en combinaison avec les réticulations métaboliques, génèrent la couleur brune caractéristique de la matrice extracellulaire fossile qui maintient en place les cellules osseuses (structures sombres et ramifiées) et les vaisseaux sanguins (structure tubulaire au centre). Crédit : J. Wiemann

Les animaux ayant un taux métabolique élevé sont endothermiques, ou à sang chaud ; les animaux à sang chaud comme les oiseaux et les mammifères absorbent beaucoup d’oxygène et doivent brûler beaucoup de calories pour maintenir leur température corporelle et rester actifs. Les animaux à sang froid, ou ectothermes, comme les reptiles, respirent moins et mangent moins. Leur mode de vie est moins coûteux en énergie que celui d’un animal à sang chaud, mais il a un prix : les animaux à sang froid dépendent du monde extérieur pour maintenir leur corps à la bonne température afin de fonctionner (comme un lézard qui se prélasse au soleil), et ils ont tendance à être moins actifs que les créatures à sang chaud.

Les oiseaux ayant le sang chaud et les reptiles le sang froid, les dinosaures se sont retrouvés au centre d’un débat. Les oiseaux sont les seuls dinosaures qui ont survécu à l’extinction massive à la fin du Cretaceous, but dinosaurs (and by extension, birds) are technically reptiles — outside of birds, their closest living relatives are crocodiles and alligators. So would that make dinosaurs warm-blooded, or cold-blooded?

“This is really exciting for us as paleontologists — the question of whether dinosaurs were warm- or cold-blooded is one of the oldest questions in paleontology, and now we think we have a consensus, that most dinosaurs were warm-blooded.” — Jasmina Wiemann

Scientists have tried to glean dinosaurs’ metabolic rates from chemical and osteohistological analyses of their bones. “In the past, people have looked at dinosaur bones with isotope geochemistry that basically works like a paleo-thermometer,” says Wiemann — researchers examine the minerals in a fossil and determine what temperatures those minerals would form in. “It’s a really cool approach and it was really revolutionary when it came out, and it continues to provide very exciting insights into the physiology of extinct animals. But we’ve realized that we don’t really understand yet how fossilization processes change the isotope signals that we pick up, so it is hard to unambiguously compare the data from fossils to modern animals.”

Another method for studying metabolism is the growth rate. “If you look at a cross-section of dinosaur bone tissue, you can see a series of lines, like tree rings, that correspond to years of growth,” says Fabbri. “You can count the lines of growth and the space between them to see how fast the dinosaur grew. The limit relies on how you transform growth rate estimates into metabolism: growing faster or slower can have more to do with the animal’s stage in life than with its metabolism, like how we grow faster when we’re young and slower when we’re older.”

The new method proposed by Wiemann, Fabbri, and their colleagues doesn’t look at the minerals present in bone or how quickly the dinosaur grew. Instead, they look at one of the most basic hallmarks of metabolism: oxygen use. When animals breathe, side products form that react with proteins, sugars, and lipids, leaving behind molecular “waste.” This waste is extremely stable and water-insoluble, so it’s preserved during the fossilization process. It leaves behind a record of how much oxygen a dinosaur was breathing in, and thus, its metabolic rate.

“We are living in the sixth mass extinction, so it is important for us to understand how modern and extinct animals physiologically responded to previous climate change and environmental perturbations, so that the past can inform biodiversity conservation in the present and inform our future actions.” — Jasmina Wiemann

The researchers looked for these bits of molecular waste in dark-colored fossil femurs, because those dark colors indicate that lots of organic matter are preserved. They examined the fossils using Raman and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy — “these methods work like laser microscopes, we can basically quantify the abundance of these molecular markers that tell us about the metabolic rate,” says Wiemann. “It is a particularly attractive method to paleontologists, because it is non-destructive.”

The team analyzed the femurs of 55 different groups of animals, including dinosaurs, their flying cousins the pterosaurs, their more distant marine relatives the plesiosaurs, and modern birds, mammals, and lizards. They compared the amount of breathing-related molecular byproducts with the known metabolic rates of the living animals and used those data to infer the metabolic rates of the extinct ones.

The team found that dinosaurs’ metabolic rates were generally high. There are two big groups of dinosaurs, the saurischians and the ornithischians — lizard hips and bird hips. The bird-hipped dinosaurs, like Triceratops and Stegosaurus, had low metabolic rates comparable to those of cold-blooded modern animals. The lizard-hipped dinosaurs, including theropods and the sauropods — the two-legged, more bird-like predatory dinosaurs like Velociraptor and T. rex and the giant, long-necked herbivores like Brachiosaurus — were warm- or even hot-blooded. The researchers were surprised to find that some of these dinosaurs weren’t just warm-blooded — they had metabolic rates comparable to modern birds, much higher than mammals. These results complement previous independent observations that hinted at such trends but could not provide direct evidence, because of the lack of a direct proxy to infer metabolism.

These findings, the researchers say, can give us fundamentally new insights into what dinosaurs’ lives were like.

“Dinosaurs with lower metabolic rates would have been, to some extent, dependent on external temperatures,” says Wiemann. “Lizards and turtles sit in the sun and bask, and we may have to consider similar ‘behavioral’ thermoregulation in ornithischians with exceptionally low metabolic rates. Cold-blooded dinosaurs also might have had to migrate to warmer climates during the cold season, and climate may have been a selective factor for where some of these dinosaurs could live.”

On the other hand, she says, the hot-blooded dinosaurs would have been more active and would have needed to eat a lot. “The hot-blooded giant sauropods were herbivores, and it would take a lot of plant matter to feed this metabolic system. They had very efficient digestive systems, and since they were so big, it probably was more of a problem for them to cool down than to heat up.” Meanwhile, the theropod dinosaurs — the group that contains birds — developed high metabolisms even before some of their members evolved flight.

“Reconstructing the biology and physiology of extinct animals is one of the hardest things to do in paleontology. This new study adds a fundamental piece of the puzzle in understanding the evolution of physiology in deep time and complements previous proxies used to investigate these questions. We can now infer body temperature through isotopes, growth strategies through osteohistology, and metabolic rates through chemical proxies,” says Fabbri.

In addition to giving us insights into what dinosaurs were like, this study also helps us better understand the world around us today. Dinosaurs, with the exception of birds, died out in a mass extinction 65 million years ago when an asteroid struck the Earth. “Having a high metabolic rate has generally been suggested as one of the key advantages when it comes to surviving mass extinctions and successfully radiating afterward,” says Wiemann — some scientists have proposed that birds survived while the non-avian dinosaurs died because of the birds’ increased metabolic capacity. But this study, Wiemann says, helps to show that this isn’t true: many dinosaurs with bird-like, exceptional metabolic capacities went extinct.

“We are living in the sixth mass extinction,” says Wiemann, “so it is important for us to understand how modern and extinct animals physiologically responded to previous climate change and environmental perturbations, so that the past can inform biodiversity conservation in the present and inform our future actions.”

Reference: “Fossil biomolecules reveal an avian metabolism in the ancestral dinosaur” by Jasmina Wiemann, Iris Menéndez, Jason M. Crawford, Matteo Fabbri, Jacques A. Gauthier, Pincelli M. Hull, Mark A. Norell and Derek E. G. Briggs, 25 May 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04770-6