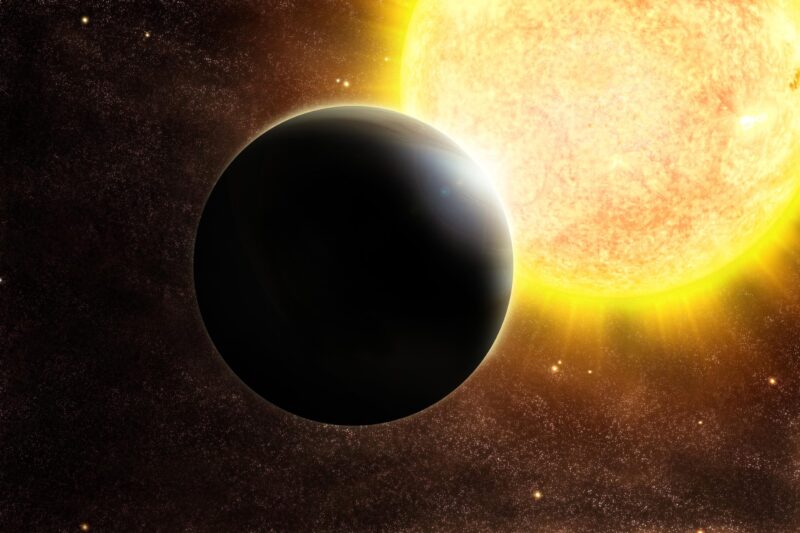

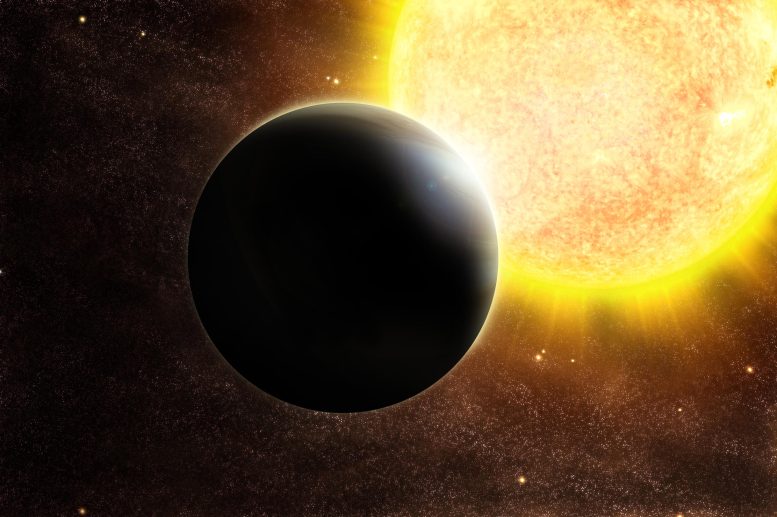

Représentation artistique d’une exoplanète de la taille de Jupiter et de son étoile hôte. Crédit : ESO

Quoi de neuf en mars ? Les planètes du matin, l’amas d’étoiles le plus proche et quelques exoplanètes à faire soi-même.

Saturn joins Venus and Mars this month in the morning sky. Beginning around March 18 or 19th, early risers may notice Saturn steadily moving toward Mars and Venus each day, to form a trio low in the east before sunrise. The crescent moon joins the crowd on the 27th and 28th. Saturn and Mars are headed toward a super-close meeting at the start of April. (More about that in next month’s video.)

See Saturn, Venus, and Mars in the pre-dawn sky in March, with Saturn becoming more noticeable after around March 18th or 19th. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Look high in the southwest on March evenings, and you’ll find the tall, Y-shaped constellation Taurus, the bull. And at the center of Taurus, forming the bull’s face, is a grouping of stars known as the Hyades star cluster. It’s the closest open star cluster to our solar system, containing hundreds of stars.

Find Y-shaped Taurus high in the southwest in the first few hours after dark, with bright Aldebaran guiding your eye to the Hyades star cluster. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Now, an open cluster is a group of stars that are close together in space and loosely bound together by their mutual gravity. These are stars that formed together around the same time, from the same cloud of dust and gas. Over time they blow away that leftover nebula material and drift apart. Because of this and their open, or diffuse, structures, they’re called “open” clusters. Our own Sun formed in a cluster like this, and studying these structures helps us understand how stars form and evolve.

Another well-known open cluster is the Pleiades, which is also located in Taurus. The Hyades and the Pleiades are actually about the same size, at about 15 or so light-years across. But the Pleiades is about 3 times farther away, so it appears more compact.

You don’t need a telescope to find the Hyades. Look for this V-shaped grouping of stars in Taurus. Use the stars of Orion’s belt as a handy pointer, leading you to bright orange Aldebaran. (Aldebaran isn’t actually part of the star cluster. It’s located halfway to the Hyades, and just happens to be visible in the foreground.)

So check out the Hyades in March, where you’ll see a handful of stars with the unaided eye, and more than a hundred with binoculars.

March skies contain several easy-to-find, bright stars that are known to have planets of their own orbiting around them. Locate these distant “suns” for yourself and you’ll know you’re peering directly at another planetary system.

First is Epsilon Tauri, the right eye of Taurus the bull. This orange dwarf star has a gas giant planet around 8 times the mass of Jupiter. Next is 7 Canis Majoris. This is the star at the heart of the dog constellation that contains blazing bright Sirius. This star is known to have two planets: a gas giant nearly twice the mass of Jupiter and another just a little smaller than Jupiter.

The constellation Canis Major contains a star – 7 Canis Majoris – known to have at least two planets. Credit: NASA/Bill Dunford

Moving on, we find Tau Geminorum, the star at the heart of Castor – northernmost of the twins in Gemini. Tau Geminorum has a huge gas giant planet 20 times the mass of Jupiter in an orbit only slightly larger than that of Earth. And finally, wheeling around to the north, is Beta Ursae Minoris, the brightest star in the bowl of the Little Dipper. This star has a 6-Jupiter-mass planet in orbit around it.

Researchers expect that most stars have a family of planets orbiting them, because forming planets is a natural part of forming stars. And now you know how to find a few of them yourself, no telescope required.