Voici une vue du réservoir après 22 mois dans les conditions prévues par le changement climatique. Crédit : Rowan McLachlan

Une étude de 22 mois fournit des conditions réalistes, selon les scientifiques.

Une étude à long terme des espèces de coraux hawaïens fournit une vision étonnamment optimiste de la façon dont ils pourraient survivre à des océans plus chauds et plus acides résultant du changement climatique.

Les chercheurs ont constaté que les trois espèces de corail étudiées ont connu une mortalité significative dans des conditions simulées pour se rapprocher des températures et de l’acidité des océans attendues dans le futur – jusqu’à environ la moitié de certaines des espèces sont mortes.

Mais le fait qu’aucune d’entre elles n’ait complètement disparu – et que certaines étaient même florissantes à la fin de l’étude – donne de l’espoir pour l’avenir des coraux, a déclaré Rowan McLachlan, qui a dirigé l’étude en tant qu’étudiant en doctorat en sciences de la terre à l’Université d’État de l’Ohio.

“Nous avons trouvé des résultats étonnamment positifs dans notre étude. Nous n’en avons pas beaucoup dans le domaine de la recherche sur les coraux lorsqu’il s’agit des effets du réchauffement des océans”, a déclaré McLachlan, qui est maintenant chercheur postdoctoral à l’Oregon State University.

Bien que les résultats soient optimistes, ils sont également plus réalistes que les études précédentes, a déclaré l’auteur principal de l’étude, Andréa Grottoli, professeur distingué de sciences de la terre à l’Ohio State.

L’étude a duré 22 mois, ce qui est beaucoup plus long que la plupart des recherches similaires, qui s’étendent souvent de quelques jours à cinq mois, a déclaré Grottoli.

“Il y a des aspects de la biologie des coraux qui prennent beaucoup de temps pour s’adapter. Il peut y avoir un creux lorsqu’ils sont confrontés à des facteurs de stress, mais après un certain temps, les coraux peuvent se recalibrer et revenir à un état normal”, a déclaré Mme Grottoli.

“Une étude qui dure cinq mois ne voit qu’une partie de l’arc de la réponse”.

La recherche a été publiée le 10 mars 2022 dans le journal. Scientific Reports.

L’augmentation des niveaux de dioxyde de carbone dans l’atmosphère a entraîné un réchauffement des océans et environ un quart du dioxyde de carbone dans l’air se dissout dans l’océan, ce qui le rend plus acide. L’augmentation de l’acidité et des températures menace le corail, a déclaré Mme Grottoli.

Dans cette étude, les chercheurs ont collecté des échantillons des trois espèces de corail les plus courantes à Hawaï : Montipora capitata, Porites compressa et Porites lobata.

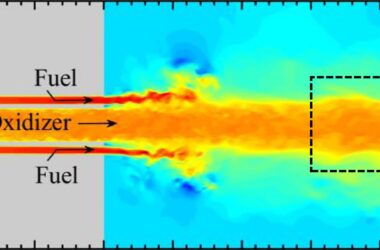

Les échantillons ont été placés dans des bassins présentant quatre conditions différentes : un bassin de contrôle avec les conditions océaniques actuelles ; une condition d’acidification de l’océan (-0. 2 unités de pH) ; une condition de réchauffement de l’océan (+2 degrés Celsius); and a condition that combined warming and acidification.

Results showed that warming oceans will hurt coral species: 61% of corals exposed to the warming conditions survived, compared to 92% exposed to current ocean temperatures.

The two Porites species were more resilient than M. capitata in the combined warming and acidification condition. Over the course of the study, survival rates were 71% for P. compressa, 56% for P. lobata and 46% for M. capitata.

“Of the coral that survived, especially the Porites species, they were coping well, even thriving,” McLachlan said. “They were able to adapt to the above-average temperature and acidity.” For example, the surviving Porites were able to maintain normal growth and metabolism.

Grottoli said M. capitata may fare better in the real world than they did in this study. The species relies heavily on zooplankton as a food source when under stress, and they may not have had as much available in the study conditions as they would in the ocean.

“We may have underestimated their capacity for resilience in this study. It may be higher on the reefs,” Grottoli said.

In most ways, though, this study did better than most at creating real-life conditions, the researchers said.

The corals were put in outside tanks designed to mimic ocean reefs by including sand, rocks, starfish, urchins, crabs and fish. These tanks also allowed natural variability in temperature and pH levels over the course of each day and over the seasons, as corals would have in the ocean.

“When you’re trying to make predictions of the long-term effects of climate change, it is important to mimic the real-world conditions, and our study does that,” Grottoli said.

“We feel strongly that this makes our findings very robust.”

The findings regarding the two Porites species may offer particular hope for corals around the world. The Porites are part of a genus of coral that is common across the world and that has a key role in reef building, so their resilience in this study is a good sign, Grottoli said.

While this study does lead to reasons for optimism, it does not mean that corals face no threat under climate change.

“We don’t know how corals will fare if changes in temperature and acidity are more drastic than what we used in this study,” McLachlan said. “Our results do offer some hope but the approximately 50% mortality we saw in some species in this study is not a small thing.”

The study also didn’t include local stressors like pollution and overfishing that may have additional negative impacts on corals in some areas, according to Grottoli.

Reference: “Physiological acclimatization in Hawaiian corals following a 22-month shift in baseline seawater temperature and pH” by Rowan H. McLachlan, James T. Price, Agustí Muñoz-Garcia, Noah L. Weisleder, Stephen J. Levas, Christopher P. Jury, Robert J. Toonen and Andréa G. Grottoli, 10 March 2022, Scientific Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-06896-z

Other co-authors were James Price, Agustí Muñoz‑Garcia and Noah Weisleder of Ohio State; Stephen Levas of the University of Wisconsin-Whitwater; and Christopher Jury and Robert Toonen of the University of Hawaii at Mānoa.

About 30 Ohio State undergraduate students also worked on the study, some through Ohio State’s Second-Year Transformational Experience Program.

Funding for the research was provided to Grottoli from the National Science Foundation and the HW Hoover Foundation and to Jury and Toonen from NSF.