Récemment, des scientifiques ont découvert un trésor de nouvelles données sur les virus à ARN dans l’océan, dont 5 500 nouvelles espèces de virus à ARN. L’analyse suggère qu’une petite partie d’entre eux ont “volé” des gènes aux organismes qu’ils ont infectés, ce qui permet d’identifier leurs fonctions dans les processus marins. Plusieurs d’entre eux pourraient contribuer à conduire le carbone absorbé dans l’atmosphère vers un stockage permanent au fond de l’océan.

Une étude identifie plus de 1 200 virus à ARN liés au flux de carbone.

De nombreux scientifiques pensent que le changement climatique est une menace importante et qu’il ne nous reste plus beaucoup de temps pour agir. En outre, de nouvelles recherches montrent que les arbres ne sont peut-être pas aussi efficaces que nous le pensions pour lutter contre le changement climatique. Ne serait-ce pas formidable si nous pouvions absorber l’excès de carbone de l’atmosphère et l’enfermer définitivement au fond de l’océan ?

Cela peut sembler de la science-fiction, mais c’est en effet du domaine du possible. L’océan est incroyablement vaste et, à mesure que nous en apprenons davantage sur les microbes qui y vivent et leur interaction avec le carbone, il est possible d’envisager des projets d’ingénierie qui pourraient accroître le stockage du carbone dans l’océan.

Une étude approfondie des 5 500 espèces de virus marins à ARN récemment identifiés par les scientifiques a révélé que plusieurs d’entre eux pourraient contribuer au stockage permanent du carbone absorbé dans l’atmosphère au fond des océans.

L’analyse suggère également qu’une petite partie de ces espèces nouvellement identifiées ont “volé” des gènes d’organismes qu’elles ont infectés, aidant les chercheurs à identifier leurs hôtes présumés et leurs fonctions dans les processus marins.

Au-delà de la cartographie d’une source de données écologiques fondamentales, la recherche permet de mieux comprendre le rôle considérable que ces minuscules particules jouent dans l’écosystème océanique.

“Les résultats sont importants pour le développement de modèles et la prédiction de ce qui se passe avec le carbone dans la bonne direction et à la bonne magnitude”, a déclaré Ahmed Zayed, chercheur en microbiologie à l’Université d’État de l’Ohio et co-auteur principal de l’étude.

La question de la magnitude est une considération sérieuse si l’on tient compte de l’immensité de l’océan.

L’auteur principal de l’étude, Matthew Sullivan, professeur de microbiologie à l’Ohio State, envisage d’identifier des virus qui, lorsqu’ils sont conçus à grande échelle, pourraient fonctionner comme des “boutons” contrôlables sur une pompe biologique qui affecte le stockage du carbone dans l’océan.

“Alors que les humains rejettent davantage de carbone dans l’atmosphère, nous dépendons de l’énorme capacité tampon de l’océan pour ralentir le changement climatique. Nous sommes de plus en plus conscients que nous pourrions avoir besoin de régler la pompe à l’échelle de l’océan”, a déclaré M. Sullivan.

“Nous serions intéressés par des virus qui pourraient se régler sur un carbone plus digestible, ce qui permettrait au système de se développer, de produire des cellules de plus en plus grandes et de couler. Et s’il coule, nous gagnerons quelques centaines ou milliers d’années supplémentaires pour échapper aux pires effets du changement climatique.

“Je pense que la société compte essentiellement sur ce genre de solution technologique, mais c’est un problème scientifique fondamental complexe à démêler.”

L’étude a été publiée le 9 juin 2022 dans la revue Science.

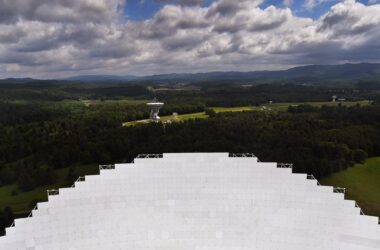

Une analyse des interactions écologiques basée sur un réseau a montré que la diversité des espèces virales à ARN était plus élevée que prévu dans l’Arctique et l’Antarctique. Crédit : Fondation Tara Ocean

Ces RNA viruses were detected in plankton samples collected by the Tara Oceans Consortium, an ongoing global study onboard the schooner Tara of the impact of climate change on the ocean. The international effort aims to reliably predict how the ocean will respond to climate change by getting acquainted with the mysterious organisms that live there and do most of the work of absorbing half the human-generated carbon in the atmosphere and producing half of the oxygen we breathe.

Though these marine viral species don’t pose a threat to human health, they behave as all viruses do, each infecting another organism and using its cellular machinery to make copies of itself. Though the outcome could always be considered bad for the host, a virus’s activities may generate benefits for the environment – for example, helping dissipate a harmful algal bloom.

The trick to defining where they fit into the ecosystem has been developing computational techniques that can coax information about RNA viral functions and hosts from fragments of genomes that are, by genomics standards, small to begin with.

“We let the data be our guide,” said co-first author Guillermo Dominguez-Huerta, a former postdoctoral researcher in Sullivan’s lab.

Statistical analysis of 44,000 sequences revealed virus community structural patterns the team used to assign RNA virus communities into four ecological zones: Arctic, Antarctic, Temperate and Tropical Epipelagic (closest to the surface, where photosynthesis occurs), and Temperate and Tropical Mesopelagic (200-1,000 meters deep). These zones closely match zone assignments for the almost 200,000 marine DNA virus species the researchers had previously identified.

There were some surprises. While biodiversity tends to broaden in warmer regions near the equator and drop close to the colder poles, Zayed said a network-based ecological interaction analysis showed the diversity of RNA viral species was higher than expected in the Arctic and Antarctic.

“When it comes to diversity, viruses don’t care about the temperature,” he said. “There were more apparent interactions between viruses and cellular life in polar areas. That tells us the high diversity we’re looking at in polar areas is basically because we have more viral species competing for the same host. We see fewer species of hosts but more viral species infecting the same hosts.”

The team used several methodological approaches to identify likely hosts, first inferring the host based on the classification of the viruses in the context of marine plankton and then making predictions based on how quantities of viruses and hosts “co-vary” because their abundances depend on each other. The third strategy consisted of finding evidence of integration of RNA viruses in cellular genomes.

“The viruses we’re studying don’t insert themselves into the host genome, but many get integrated into the genome by accident. When it happens, it’s a clue about the host because if you find a virus signal within a host genome, it’s because at some point the virus was inside the cell,” Dominguez-Huerta said.

While most dsDNA viruses had been found to infect bacteria and archaea, which are abundant in the ocean, this new analysis found that RNA viruses mostly infect fungi and microbial eukaryotes and, to a lesser extent, invertebrates. Only a tiny fraction of the marine RNA viruses infect bacteria.

The analysis also yielded the unanticipated discovery of 72 discernible functionally different auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) sprinkled among 95 RNA viruses, which provided some of the best clues as to what kinds of organisms these viruses infect and what metabolic processes they’re trying to reprogram in order to maximize the “fabrication” of viruses in the ocean.

Further network-based analysis identified 1,243 RNA virus species connected to carbon export and, very conservatively, 11 were implied to be involved in promoting carbon export to the bottom of the sea. Of those, two viruses linked to hosts in the algae family were selected as the most promising targets for follow-up.

“Modeling is getting to the point where we can take bags of genes from these large-scale genomic surveys and paint metabolic maps,” said Sullivan, also a professor of civil, environmental and geodetic engineering and founding director of Ohio State’s Center of Microbiome Science.

“I’m envisioning our use of AMGs and these viruses that are predicted to infect particular hosts to actually dial up those metabolic maps toward the carbon we need. It’s through that metabolic activity that we probably need to act.”

Reference: “Diversity and ecological footprint of Global Ocean RNA viruses” by Guillermo Dominguez-Huerta, Ahmed A. Zayed, James M. Wainaina, Jiarong Guo, Funing Tian, Akbar Adjie Pratama, Benjamin Bolduc, Mohamed Mohssen, Olivier Zablocki, Eric Pelletier, Erwan Delage, Adriana Alberti, Jean-Marc Aury, Quentin Carradec, Corinne da Silva, Karine Labadie, Julie Poulain, Tara Oceans Coordinators§. , Chris Bowler, Damien Eveillard, Lionel Guidi, Eric Karsenti, Jens H. Kuhn, Hiroyuki Ogata, Patrick Wincker, Alexander Culley, Samuel Chaffron and Matthew B. Sullivan, 9 June 2022, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abn6358

Sullivan, Dominguez-Huerta and Zayed are also team members in the EMERGE Biology Integration Institute at Ohio State.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Ohio Supercomputer Center, Ohio State’s Center of Microbiome Science, a Ramon-Areces Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship, Laulima Government Solutions/NIAID and France Génomique. The work was also made possible by the unprecedented sampling and science of the Tara Oceans Consortium, the nonprofit Tara Ocean Foundation and its partners.

Additional co-authors on the paper include James Wainaina, Jiarong Guo, Funing Tian, Akbar Adjie Pratama, Benjamin Bolduc, Mohamed Mohssen and Olivier Zablocki, all of Sullivan’s lab; Jens Kuhn of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Alexander Culley of the Université Laval; Erwan Delage, Damien Eveillard and Samuel Chaffron of the Nantes Université; Lionel Guidi of the Sorbonne Université; Hiroyuki Ogata of Kyoto University; Chris Bowler of the Ecole Normale Supérieure; Eric Karsenti of the the Ecole Normale Supérieure and European Molecular Biology Laboratory; and Eric Pelletier, Adriana Alberti, Jean-Marc Aury, Quentin Carradec, Corinne da Silva, Karine Labadie, Julie Poulain and Patrick Wincker of Genoscope.