Les chercheurs ont simulé et présenté une expérience à faible coût permettant de produire et d’étudier les premières phases de ce processus d’une manière qui était auparavant considérée comme irréalisable avec la technologie actuelle.

Des scientifiques simulent un processus explosif déroutant qui se produit dans tout l’univers.

Les mystérieux sursauts radio rapides sont parmi les phénomènes les plus perplexes de l’univers, libérant autant d’énergie en une seconde que le Soleil en un an. Des chercheurs de l’université de Princeton, du Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) du ministère américain de l’énergie (DOE) et du SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory ont simulé et proposé une expérience rentable permettant de produire et d’observer les premiers stades de ce processus d’une manière que l’on pensait auparavant impossible avec la technologie actuelle.

Des corps célestes tels que des étoiles à neutrons, ou effondrées, surnommées magnétars (aimant + étoile), enfermés dans de puissants champs magnétiques, sont responsables des remarquables explosions dans l’espace. Selon la théorie de l’électrodynamique quantique (QED), ces champs sont si intenses qu’ils transforment le vide spatial en un plasma made of matter and anti-matter in the form of pairs of negatively charged electrons and positively charged positrons. Emissions from these pairs are thought to be responsible for the powerful fast radio bursts.

Pair plasma

The matter-antimatter plasma, called “pair plasma,” stands in contrast to the usual plasma that fuels fusion reactions and makes up 99% of the visible universe. This plasma consists of matter only in the form of electrons and vastly higher-mass atomic nuclei, or ions. The electron-positron plasmas are comprised of equal mass but oppositely charged particles that are subject to annihilation and creation. Such plasmas can exhibit quite different collective behavior.

“Our laboratory simulation is a small-scale analog of a magnetar environment,” said physicist Kenan Qu of the Princeton Department of Astrophysical Sciences. “This allows us to analyze QED pair plasmas,” said Qu, the first author of a recent study showcased in Physics of Plasmas as a science highlight, and also the first author of a paper in Physical Review Letters that the present paper expands on.

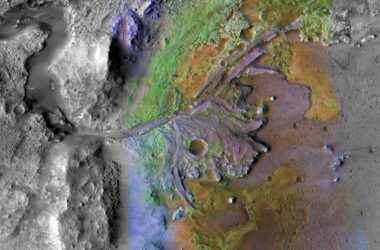

Physicist Kenan Qu with images of fast radio burst in two galaxies. The top and bottom photos on the left show the galaxies, with digitally enhanced photos shown on the right. Dotted oval lines mark burst locations in the galaxies. Credit: Qu photo by Elle Starkman; galaxy photos courtesy of NASA; collage by Kiran Sudarsanan.)

“Rather than simulating a strong magnetic field, we use a strong laser,” Qu said. “It converts energy into pair plasma through what are called QED cascades. The pair plasma then shifts the laser pulse to a higher frequency,” he said. “The exciting result demonstrates the prospects for creating and observing QED pair plasma in laboratories and enabling experiments to verify theories about fast radio bursts.”

Laboratory-produced pair plasmas have previously been created, noted physicist Nat Fisch, a professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University and associate director for academic affairs at PPPL who serves as the principal investigator for this research. “And we think we know what laws govern their collective behavior,” Fisch said. “But until we actually produce a pair plasma in the laboratory that exhibits collective phenomena that we can probe, we cannot be absolutely sure of that.

Collective behavior

“The problem is that collective behavior in pair plasmas is notoriously hard to observe,” he added. “Thus, a major step for us was to think of this as a joint production-observation problem, recognizing that a great method of observation relaxes the conditions on what must be produced and in turn leads us to a more practicable user facility.”

The unique simulation the paper proposes creates high-density QED pair plasma by colliding the laser with a dense electron beam traveling near the speed of light. This approach is cost-efficient when compared with the commonly proposed method of colliding ultra-strong lasers to produce the QED cascades. The approach also slows the movement of plasma particles, thereby allowing stronger collective effects.

“No lasers are strong enough to achieve this today and building them could cost billions of dollars,” Qu said. “Our approach strongly supports using an electron beam accelerator and a moderately strong laser to achieve QED pair plasma. The implication of our study is that supporting this approach could save a lot of money.”

Currently underway are preparations for testing the simulation with a new round of laser and electron experiments at SLAC. “In a sense what we are doing here is the starting point of the cascade that produces radio bursts,” said Sebastian Meuren, a SLAC researcher and former postdoctoral visiting fellow at Princeton University who coauthored the two papers with Qu and Fisch.

Evolving experiment

“If we could observe something like a radio burst in the laboratory that would be extremely exciting,” Meuren said. “But the first part is just to observe the scattering of the electron beams and once we do that we’ll improve the laser intensity to get to higher densities to actually see the electron-positron pairs. The idea is that our experiment will evolve over the next two years or so.”

The overall goal of this research is understanding how bodies like magnetars create pair plasma and what new physics associated with fast radio bursts are brought about, Qu said. “These are the central questions we are interested in.”

This joint work was supported by National Nuclear Security Agency (NNSA) grants awarded to Princeton University through the Department of Astrophysical Sciences and by DOE grants awarded to Stanford University.

Reference: “Collective plasma effects of electron–positron pairs in beam-driven QED cascades” by Kenan Qu, Sebastian Meuren and Nathaniel J. Fisch, 21 April 2022, Physics of Plasmas.

DOI: 10.1063/5.0078969