C’est une première mondiale très prometteuse ! Des scientifiques de l’Université de Louvain (UCLouvain) ont réussi à identifier la clé qui permet au virus Covid d’attaquer les cellules. Mieux encore, ils ont également réussi à fermer la serrure pour bloquer le virus et empêcher son interaction avec la cellule, autrement dit, empêcher l’infection. Cette découverte, publiée dans la revue Nature Communicationssoulève un immense espoir : celui de développer un antiviral, sous forme d’aérosol, qui permettrait d’éradiquer le virus en cas d’infection ou de contact à risque ! Crédit : Université de Louvain (UCLouvain)

Malgré l’efficacité des campagnes de vaccination Covid-19 dans le monde, la menace que représente le SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus still exists. To begin with, a new SARS-CoV-2 variant may emerge that is resistant to current vaccines. Second, the long-term efficacy of the vaccines is unknown. Finally, cases of acute infection are still being reported. Despite this, there is currently no effective treatment.

To create an antiviral that prevents infection, researchers must first understand the exact mechanisms (at the molecular level) by which the virus infects a cell. This is the task that David Alsteens’ team at the University of Louvain’s Institute of Biomolecular Sciences and Technologies (UCLouvain) in Belgium has been working on for the past two years. They investigated the interaction between sialic acids (SAs), which are types of sugar residues found on the surface of cells, and the spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV-2 (using atomic force microscopy) in a study to be published today (May 10, 2022) in the journal Nature Communications. What is the goal? To understand its role in the infection process.

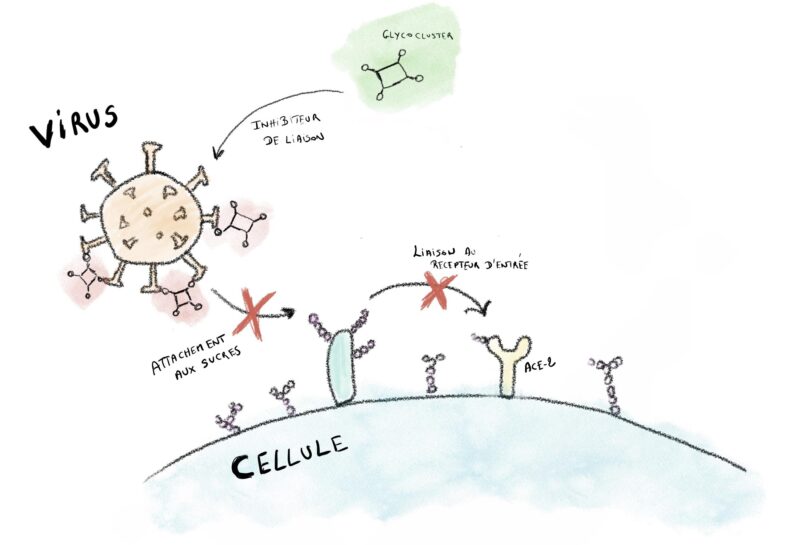

What do we already know? That all cells are decorated with sugar residues. And what function do these sugars serve? To promote cell recognition, which allows viruses to identify their targets more easily. But, also, to facilitate their point of attachment to allow them to enter their host cell and thus initiate their infection.

What did the UCLouvain researchers discover? They identified a variant of these sugars (9-O-acetylated) that interacted more strongly with the S protein than other sugars. In short, they found the set of keys that allows viruses to open the cell door. Why a set of keys? The virus is composed of a series of spike proteins with a suction cup effect that allows them to bind to the cell and ultimately enter. The more keys the virus finds, the better the interaction with the cell and the wider the door will open. Hence the importance of finding out how the virus manages to multiply the entry keys.

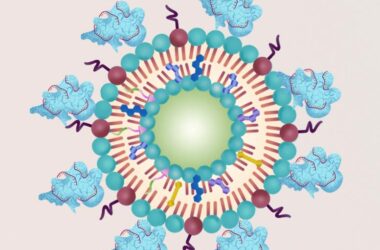

This is where the second discovery of the UCLouvain researchers comes in: they decided to catch the virus in its own trap, by preventing it from binding to its host cell. How? By blocking the S protein’s points of attachment and thus suppressing any interaction with the cell surface. As though a padlock had been attached to the lock of the cell’s front door. One of the conditions for this is that the interaction between the virus and the agent blocking it is stronger than the one between the virus and the cell. In this particular case, the scientists demonstrated that multivalent structures (or glycoclusters) with multiple 9-O-acetylated sialic acids on their surface (the famous sugar variant revealed by the UCLouvain team) are able to block both binding and infection by SARS-CoV-2. If the virus doesn’t attach to the cells, it can’t enter and therefore dies (lifetime 1 to 5 hours). This blocking action prevents infection.

Within the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, the various vaccines primarily addressed the SARS-CoV-2 mutations but not the virus as a whole. This UCLouvain discovery has the advantage of acting on the virus, independently of the mutations.

What’s next? The UCLouvain team will carry out tests on mice in order to apply this blocking of virus binding sites and observe whether this works on the organism. The results should be available soon, leading to the development of an antiviral based on these sugars, administered by aerosol, in case of infection or high-risk contact.

This discovery is also interesting for the future, to counter other viruses with similar attachment factors.

Reference: “Multivalent 9-O-Acetylated-sialic acid glycoclusters as potent inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 infection” 10 May 2022, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-30313-8